Women in Translation: In Conversation with Angela Carr

Today’s #WITMonth interviewee is poet and translator Angela Carr, whose fourth poetry collection, Without Ceremony, is forthcoming from Book*hug on October 15, 2020. Two of Carr’s previous collections, Here in There and The Rose Concordance, were also published by Book*hug, as was Carr’s translation of Québécoise poet Chantal Neveu’s Coït. Her deep immersion in poetry has a clear effect on her translation of it: Carr’s work is both thorough and tensile, as amenable to feeling as it is to literal, arguably surface-level meaning. As she says in her interview, “Poetic language makes us feel things, so translators of poetry have to think about the way it does this, the deeper associations created by sonic structures, resonance and silences.” We hope you enjoy reading these and other insights as much as we did.

B*H: What should people know about translation that they might not know?

AC: First, in my experience, translating poetry is a form of creative writing. Though some take issue with this view, arguing that a translator’s so-called fidelity to the author means that translation can’t be creative. But when I say that translating poetry is creative, I’m not suggesting I write whatever comes to mind, call it “translation” and put another author’s name on it! What I mean to say is that translating poetry means more than translating the surface meaning of a particular set of phrases or words. It means to reach for deeper poetic structures and to try to convey these across languages. This is not easy. Poetic language makes us feel things, so translators of poetry have to think about the way it does this, the deeper associations created by sonic structures, resonance and silences. How do you translate that particular relationship between sound and silence, for example?

Secondly, I often encounter this idea that a writer should choose to be an author or a translator, that these are two very divergent and separate professional categories. But the fact of the matter is that poetry needs to be translated by poets. A translator needs to have a developed poetic sensibility to translate poetry well. And if you start to look carefully, you will see that many of the poets you read have translated poetry, at least at some point during their writing life.

B*H: What is your favourite “non-English” word and its meaning?

AC: I’m always drawn to untranslatable words, because they present us with a conceptual challenge and show us that there is a completely different way of seeing the world and therefore of living. So they represent freedom. There are many such words. Eventually if necessary these untranslatable words get absorbed across languages. Of course, English is always already full of “non-English” words by definition for this reason—the history of the English language is already one of appropriation.

But in relation to French: How about flâner, for example? How do you say this in English? To walk or to wander or to saunter don’t quite cut it. To walk aimlessly doesn’t work either. There is a whole orientation to the world implied in the verb flâner that transcends the literal activity of walking in cities or in crowds. Is it an activity or an affect? Is it about leisure? This opens a whole social and political question. And who can enjoy this leisurely activity? How do factors like gender, sexuality, race, and social class affect one’s experience as a flaneur?

B*H: What drew you to translation, and what draws you to it now?

AC: Honestly, I was originally drawn to translation because I lived for a long time in the linguistically dynamic city of Montréal, where people code-switch all the time. In addition, I love literature, I have three degrees in literature, and was always drawn to reading poetry in other languages, by international writers, and also across historical periods. At a certain point, I felt it was my responsibility to participate and build on the work of Canadian literature in translation, with a particular focus on writing by women in Québec. So my interest in translation was twofold in this way: first, it was about the joy of translation as a poetic creative act, and later it was based on a more academic/professional commitment to contribute to dialogue across communities. I decided to translate Chantal Neveu’s book Coït because I thought its experimental formal structure was interesting, and I wanted to make that available to anglophone friends and colleagues.

B*H: Can you recommend a recently published translation?

AC: There are so many, but I’m going to focus on one title I adore in Book*hug’s list: Secession/Insecession by Erín Moure and Chus Pato. It’s 51% authored by Moure and 49% a translation of Secession by Galician poet Chus Pato. This book is really a “translator’s translation” because it raises fascinating conceptual issues relevant to authorship, translation, nationalism and the conditions of literary production. I wrote an article about this book, published inSillages Critiques, so I won’t belabour my description here… Personally, I’m currently reading The Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector translated by Katrina Dodson and published by New Directions.

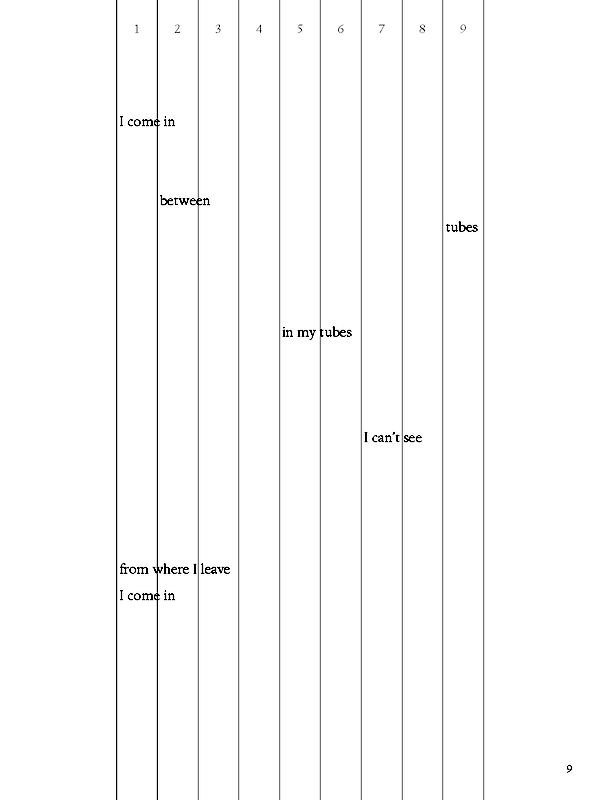

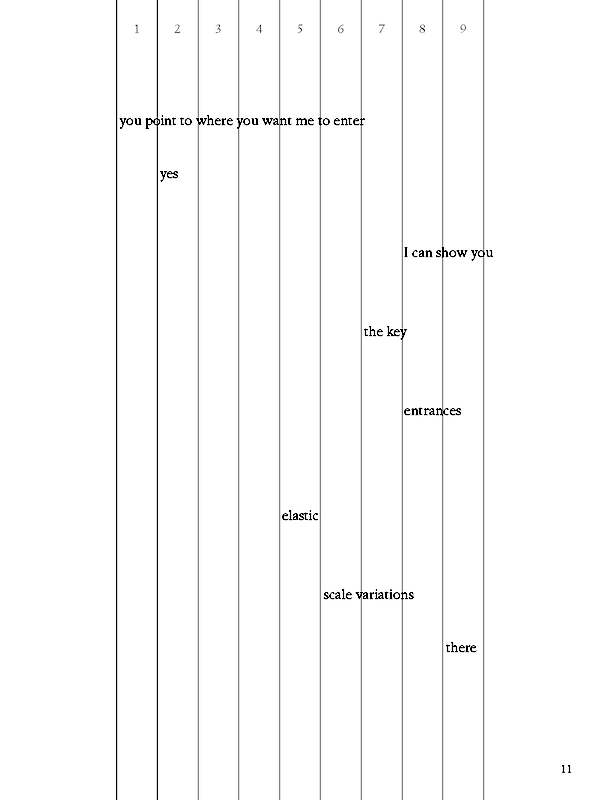

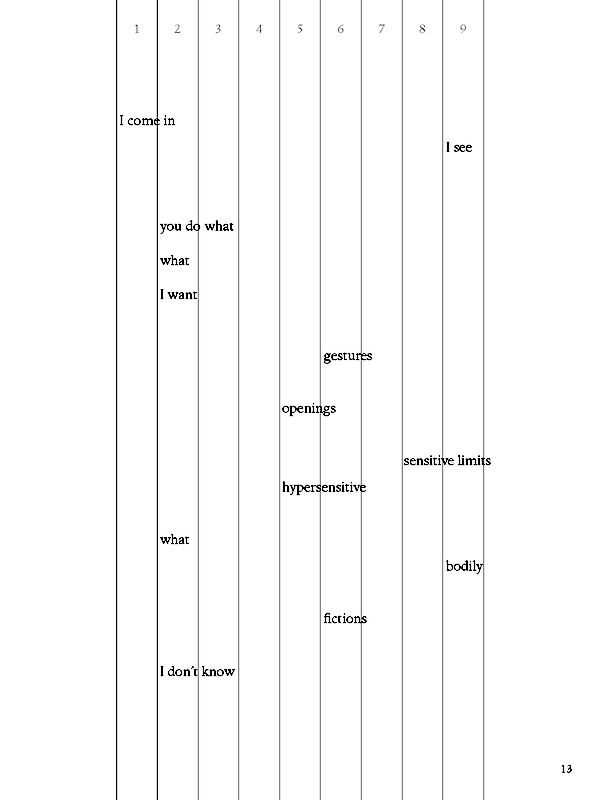

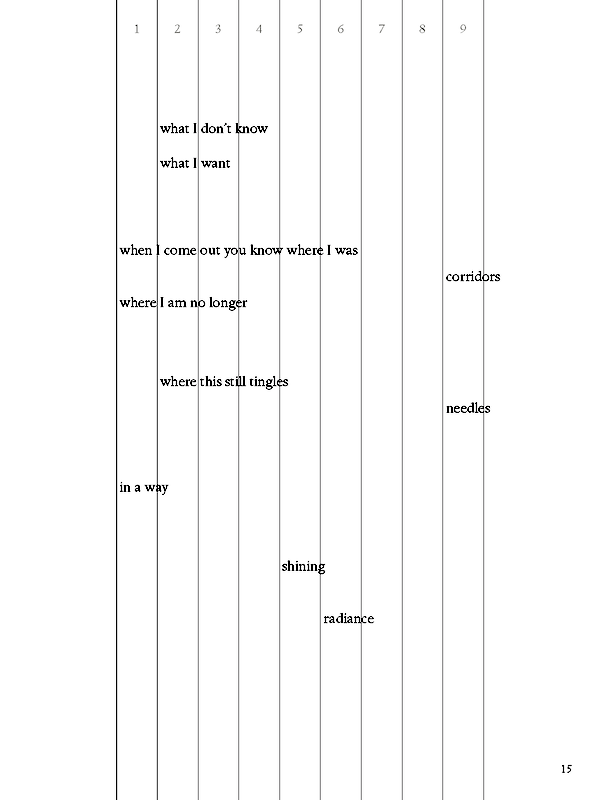

Please enjoy the following excerpt from Carr’s 2012 translation of Chantal Neveu’s Coït. Of her translation, fellow poet and translator Christian Hawkey writes, “Dear Angela Carr: thank you for affirming, via translation, a book that is so uncommonly generous… that affirms (like translation) the world with the world.” Stay tuned for more interviews and excerpts in celebration of #WITMonth!

Angela Carr is the author of three previous poetry collections, including Here in There (shortlisted for the A. M. Klein Prize for Poetry), The Rose Concordance, and Ropewalk (shortlisted for the McAuslan First Book Prize). Angela has also translated poetry books by Nicole Brossard (Ardour) and Chantal Neveu (Coït). She studied Creative Writing and Literature at Concordia University in Montreal, and later earned a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Montreal. She currently resides in New York City, where she teaches Literary Studies at the New School University.