Women in Translation: In Conversation with Kari Dickson

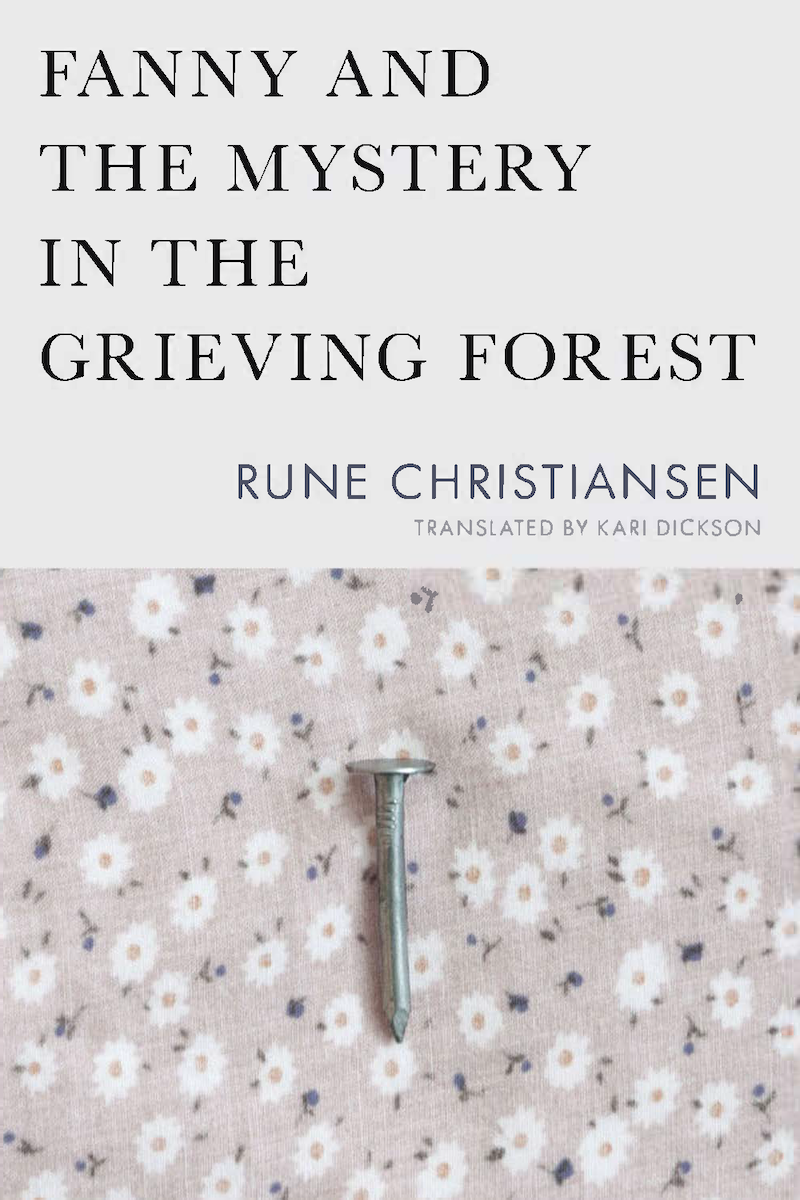

Our celebration of Women in Translation Month continues! Today, we’re in conversation with Kari Dickson! For Book*hug, Dickson translated Norwegian author Rune Christiansen’s beautiful novel Fanny and the Mystery in the Grieving Forest, which was shortlisted for Norway’s Brage Prize in 2017. Of course, her work doesn’t end there: over the years, she’s translated dozens of books from Norwegian into English, exposing audiences worldwide to beautifully written—and, of course, beautifully translated—literature.

Readers in need of more gems from Norway—a need for which we don’t blame you—can look forward to next autumn. Together with Rachel Rankin, Dickson is co-translating Mona Høvring’s award-winning novel, Because Venus Crossed an Alp Violet on the Day I Was Born, which Book*hug will publish in Fall 2021. In the meantime, we’re grateful to hear Dickson’s thoughts on her work, and are even more grateful to have learned the word solvegg. (Now we just need an utepils…)

B*H: What should people know about translation that they might not know?

KD: It’s harder and more rewarding than you might think. Knowing a language doesn’t necessarily mean you can translate; many words have more than one meaning and you need to understand the cultural context to get the right meaning. You also need to be a reader and to write your own language well.

B*H: What is your favourite “non-English” word and its meaning?

KD: I have many! And I love compounds in particular, so here’s one: solvegg: the wall that catches the sun. After a long, dark winter, everyone dreams of sitting against the “solvegg” with an “utepils” (a beer drunk outside).

B*H: What drew you to translation, and what draws you to it now?

KD: I used to work in theatre, and someone knew that I was part Norwegian so asked if I could do a literal translation of an Ibsen play and I said yes. As I worked, I thought, I can do, this is my thing, the combining of literature and language, and the cultural knowledge and understanding of two cultures. That was a long time ago now, and I’m so deep into it that it’s more of a lifestyle than a job. I feel extraordinarily fortunate to have found my niche, and one that allows me to explore different styles, genres, topics and opens up the world.

B*H: What are you currently translating, if anything?

KD: I finished translating two books just before the summer. One is a travel book, The Border by Erika Fatland, which will be published by MacLehose Press, UK, in the autumn, in which she circumnavigates Russia to discover what it means to have this vast country as a neighbour. The other, a novel: Present Tense Machine (working title) by Gunnhild Øyehaug, which will be published by FSG, USA in 2021. Two women—perfect for Women in Translation Month. I am currently fact-checking Erika’s latest book on the Himalayas, and about to do two sample translations of books by women, Kjersti Annesdatter Skomsvold and Siri Helle, so very much in the mood. And then a novel by Mona Høvring for Book*hug!

B*H: Can you recommend a recently published translation?

KD: If you haven’t read it already, Hanne Ørstavik’s Love, translated by Martin Aitkin, published by Archipelago, USA, 2018/And Other Stories, UK, 2019. Winner of Pen Translation Prize 2019.

Please enjoy the following excerpt from Fanny and the Mystery in the Grieving Forest, which Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer, author of All the Broken Things, calls “beguiling, haunting, and erotic in equal measure.”

“A shimmering musing on grief,” writes Kuitenbrouwer. “Fanny is both ecstatic fairytale and Gothic novel.” As part of our Literature in Translation Series, Fanny is eligible for a 25% discount until August 30th. Stay tuned for more interviews and excerpts in celebration of #WITMonth!

Was This the Day of the Last Matchstick?

Perhaps it’s the case that an action or decision that can’t be interpreted is worthless. Fanny switched off all the lights at the end of the day. The same ritual every evening: first the grey standard lamp in the living room, then the one on the sideboard in the dining room, which had over a hundred mirrored droplets, wafer-thin shards that trembled every time she walked past, showering light onto the floor, the walls—endlessly fascinating, like a living being. She left one of the fluorescent lights under the kitchen cupboard on, so she wouldn’t need to stumble about if she woke up in the middle of the night and wanted a glass of water. Everything was the same as always, routine, only that evening something caught her eye: a nail. It lay between the stove and the countertop. It must have been lying there, hidden, for a small eternity. Ever since her father put up the little row of hooks for the tea towels and hand towels. It twinkled at her. And Fanny picked it up, felt the point, studied it as though it were a remarkable find. She took it with her into the bathroom, placed it on the side of the sink while she brushed her teeth, and as soon as she was in bed, she popped it under the pillow. Was it her father who had dropped it? Instinctively, she reached for it, held it in her hand. She wasn’t going to get any sleep. She knew it already. She was used to sleeplessness. Who knows, perhaps she even courted it, she certainly never fled from it. But how can you flee from insomnia? That is like saying you can give yourself up to sleep, that it’s a choice, self-willed, and thus that it’s pathetic and passive simply to lie there in the dark without giving yourself over to dreams, to rest. Fanny turned on the light and examined the nail with indifference. She ran it down the thin skin on the inside of her arm, made a scratch, slowly, then another, faster, and then an even deeper one. It stung, a burning pain that eased as soon as the blood trickled out. She squinted at the nail, put it back under her pillow, turned off the light.

The morning wind blew in, the light found her. She rubbed her eyes and it struck her that she had dreamed about something that didn’t concern her, or so she felt—what she had imagined really had nothing to do with her, and yet she felt out of sorts when she got up. She had been walking around in a forest, and in a clearing had come across a lifeless person, a girl of about her own age, and having stared in disbelief for a long time, for too long, she turned away and staggered home to tell her parents about the girl. But halfway down the hill, she discovered she was being followed, followed by something insane, a viscous, all-enveloping mass, and it poured down the hillside, swelled, caught up with her, pushed against her spine, hit the back of her head, thrust her neck forward so she stumbled on some loose stones. It was death that was forcing itself so mercilessly upon her, and now death wasn’t anything or anyone, now death was just pitiful, poor air, barely breathable, or rather, it was like a lack of air, a lack of oxygen. Death was time in a rush or at a standstill, a strange hour that played havoc with the normal order of things and broke down all meaning, all faith. Or perhaps death was all of this at once, because it did not need to hide itself in this or that. It did not keep its distance, not even when one was a young person wandering peacefully around in the forest in a dream that had not warned of any danger, a dream that had no idea where death was, where it lived. And now death attached itself to her, now death held on to Fanny, like a sign, a black mark on the palm of her hand. She went out into the bathroom and thought: I take back everything I’ve said and done. No false humility, no confident conviction, just difficult, bewildering beginnings, one after the other, just decisions and effort. She washed off the dried blood and examined the thin scratches in the light. The skin around the deepest cut was swollen and warm. She turned on the tap again and let the cold water run over it. In the mirror, she was a stranger, not distorted but changed—her full lips were dry and cracked, her skin was pallid, with a bluish tinge under the eyes. Was there anything more pitiful than secret, self-inflicted humiliation? And on the early train into town, at school and later on the familiar journey home—she could feel it, she was now tormented by the need to understand. It was as though she needed both distractions and rest to be able to tell herself how closely she was connected to the nail, to the defeat it had entailed. What invites trust and spontaneous confessions more than loss and loneliness?

❧

Kari Dickson is a literary translator. She translates from Norwegian, and her work includes crime fiction, literary fiction, children’s books, theatre and nonfiction. She is also an occasional tutor in Norwegian language, literature and translation at the University of Edinburgh, and has worked with BCLT and the Writers’ Centre Norwich. She lives in Edinburgh.