Women in Translation: In Conversation with Jessica Moore

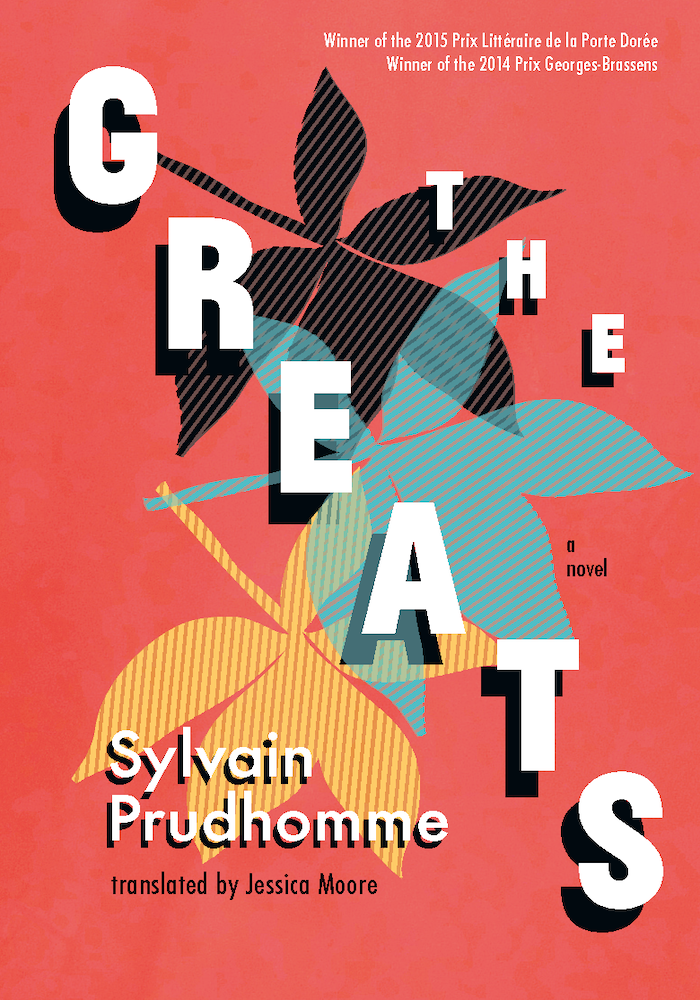

Our celebration of Women in Translation continues! Today we’re in conversation with writer and Booker International Prize nominee, not to mention genre-defying singer-songwriter, Jessica Moore. She has translated many important titles, including Sylvain Prudhomme’s award-winning novel The Greats. We’re incredibly grateful to be able to share her thoughts with you today.

B*H: What should people know about translation that they might not know?

JM: That it is not the same to translate into and out of a language. Some people assume that, since literary translation requires a certain fluency in two languages, the translator should be able to go both ways. But comprehending and articulating are two very different skills. Except for one or two rare exceptions, every literary translator I know only works in one direction—into their “mother tongue.” For me personally there is a sensitivity I have in English (my first language) that is unmatched in French even if I read and understand French fluently. When I translate from French to English, I’m drawing upon a lifetime lived in this language, and a lifetime as a writer, attuned to the shape of words.

B*H: What is your favourite “non-English” word and its meaning?

JM: Oh! This is a nice question. Right now my favourite non-English word—which has nothing to do with my working language of French and everything to do with reading Leanne Betasamosake Simpson—is the Anishinaabe word/phrase mino-bimaadiziwen, which means “living a good life,” or the way of a good life. This word/phrase and the expansive notion it points toward (which I know I only see the tiniest iceberg tip of) feels so intriguing, active, inspiring.

B*H: What drew you to translation, and what draws you to it now?

JM: I was first drawn to translation through a love of writing—I always wanted to be a writer, and this is precisely what literary translation requires—combined with a love of puzzling things out. My favourite book as a kid was a spin on Through the Looking Glass called Alice in Puzzle-Land. This relates to another favourite childhood pastime of re-arranging items, such as spices in the cupboard. It is so pleasing when words land just so, in a satisfying arrangement.

B*H: What are you currently translating, if anything?

JM: I’m editing my translation of French author Maylis de Kerangal’s novel Un monde à portée de main (which will be translated as Painting Time), about a young painter named Paula who learns the art of trompe-l’œil and ends up working on the replica of the Lascaux Cave, where an incredible array of Paleolithic paintings were discovered in 1940. I’m also translating articles for BESIDE magazine on a rolling basis, currently focused on Black Canadian and American youth, and equal access to nature.

B*H: Can you recommend a recently published translation?

JM: Neither is very recent, but the last book in translation I read was Drive Your Plough Over the Bones of the Dead, by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones—a strange and hard-to-place, dark, feminist, fairytale-esque story set in rural Poland. And I suppose I could cheekily recommend The Greats, my translation of the novel by Sylvain Prudhomme, a laid-back but simmering song of a book, that came out with Book*hug in 2017.

Please enjoy the following excerpt from Jessica Moore’s translation of Sylvain Prudhomme’s The Greats, which we, too, “cheekily recommend”! Originally published as Les Grands by Gallimard in France, the novel won both the 2015 Prix Littéraire de la Porte Dorée and the 2014 Prix Georges Brassens, and the magazine Lire named it the “Révélation française de l’année 2014.” Martha Baillie, author of If Clara and The Search for Heinrich Schlögel, praised Moore’s “splendid translation,” writing that it “captures the rhythm of Prudhomme’s heart-felt homage to Guinea-Bissau, the vivid detail of his night stroll through the country’s shifting music scene, its ruthless, recurring, political upheavals and its ongoing fight for independence.”

Excerpt from The Greats

Outside, the city was waking up from its siesta. It was the time of afternoon when the heat had passed its peak—the sun had begun its descent, the light grew soft again. Colour returned to the streets, the earth redder between the bare roots, the moss more gold on the facades of buildings, the leaves of the mango trees a deeper green. The rains had stopped a week ago and with the plants and trees revived, having been watered for months, the men and women too came back to life, happy to linger again in front of houses, to come and go along the slanted streets.

Couto and Esperança left their little room. The neighbours saw them rub their eyes, adjust their clothes, saw Couto lift his arm to hail a taxi bobbing between potholes. Esperança got in. Couto watched her leave, heading toward the hotel where she worked every afternoon. He took the red paths through Pefine toward Nunu’s bar.

Before leaving, Esperança had asked him if he didn’t for once want to make an effort, for once put on something nicer than his perpetual jean jacket worn through at the elbows and wrists, a pair of pants less pitiful than his old jeans bleached white from the sun.

Dammit Couto don’t you want to try and look decent for once.

Leave it be, said Couto. Leave it be you don’t get my style, we’ll just argue again over nothing.

Everyone’s going to be there, said Esperança. Everyone will want to give you their condolences.

Couto pushed up the sleeves of his jacket, slipped silver bracelets onto his wrists.

I said leave it be, there’s no point, we’re just going to fight again.

He asked her for two thousand francs, enough for the evening. She gave him a thousand, saying that for what he would do with it, in other words throw it out the window, that would be more than enough.

He took the bill held out through the taxi’s open window, pulled his shirt closed around his big scrawny ribs, and headed off between the houses, his long skinny body slumping over the dips and bumps.

Saturnino Bayo, called “Couto.” Mix of faded greying glory and incorrigible brat whose pride prevented him from working more than a few hours a day, a few days a month. Eternally idle Lord, eternally broke, but who had only to drag his sorry ass through the streets for all eyes to linger on him.

Couto the dutur di biola, the great maestro of the guitar. Couto the dun, the captain.

Dun di ke, captain of what, dun di tuda, captain of everything, dun di nada, captain of nothing at all.

❧

Jessica Moore is a Toronto-based author and translator. Her collection of poems, Everything, now (Brick Books 2012), is partly a conversation with her translation of Turkana Boy (Talonbooks 2012) by Jean-François Beauchemin, for which she won a PEN America Translation Award. Mend the Living, Jessica’s translation of the novel by French author Maylis de Kerangal, was nominated for the 2016 Man Booker International Prize and won the £30,000 Wellcome Prize in 2017. Her next book, The Whole Singing Ocean is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in 2021. Learn more at www.jessicamoore.ca.