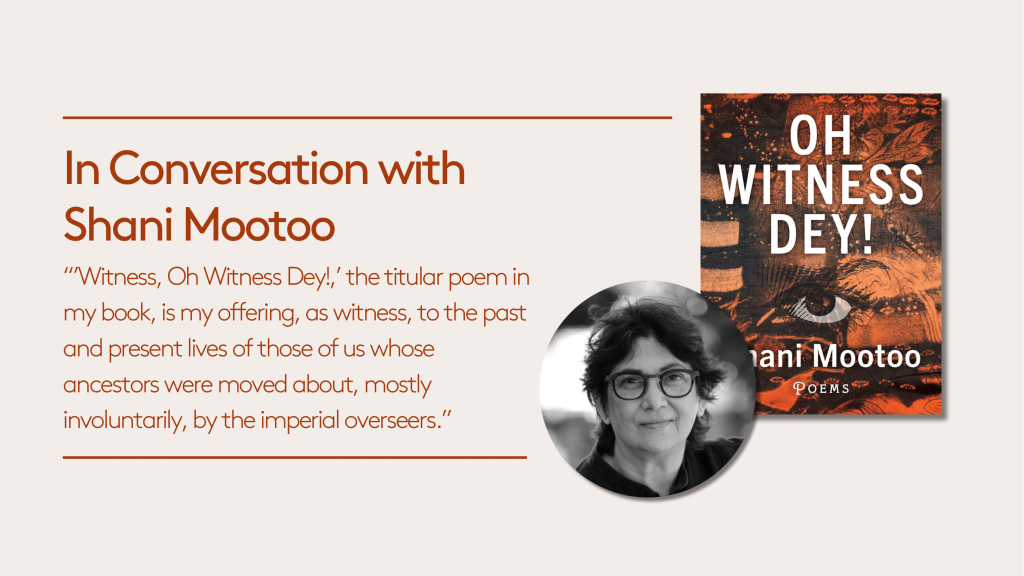

“My Offering as a Witness”: In Conversation with Shani Mootoo

Today, Shani Mootoo sits down with Shazia Hafiz Ramji, who worked with Shani on her newest collection of poetry, Oh Witness Dey!

SM: Thanks Shazia for these great questions. Before I respond, I’d like to say that the process of editing with you was exciting, as you knew, for the most part, the material I was working with. More than knowing it, you felt it. Out of that process came a book, and a friendship. I am grateful for all of it.

SHR: Shani, tell us what “witness” means for you?

SM: I first came across the notion of the enlightened witness in the writings of the Jewish-Polish-Swiss psychologist and philosopher Alice Miller. In her article “The Essential Role of an Enlightened Witness in Society”, Miller states that people who have “been lucky enough to find enlightened and courageous witnesses, people who helped them to recognize the injustices they suffered, to give vent to their feelings of rage, pain and indignation at what happened to them….never become criminals.”

I turned to Miller’s work to try to find a way to deal with my own traumas of childhood. Miller’s notion of a witness shone a credible light on why, rather than becoming a person whose actions would imitate in adulthood the ills experienced in childhood, I would instead engage in works of creativity that sought to make order out of chaos, to find answers to hard questions, and to search for possibilities of beauty. In the midst of harm, there had been, for me, several loving people who validated me and for whom I could have done no wrong. My childhood witnesses showed me an alternative view of the world; there was love in the world, it was an amazing thing, was there to be searched for, and could even be created.

When I was commissioned by Spike Island Gallery in Bristol England to write a work for the catalogue of American artist Candice Lin’s touring exhibition Pigs and Poison, I was reminded, in her work, of the idea of the witness. In Lin’s three-floor installation work showcasing the story of Chinese indentured labourers in the United States of America, anthropomorphic figures wearing ceramic masks that bridle their mouths are stationed at the exhibition’s entrance. Though bridled, they are sentinels, guardians who watch and see, who are witnesses to a plethora of injustices, and who validate the inevitable pain, and the equally inevitable triumphs.

Lin’s story of Chinese indentured labourers resonated with that of Indian indentured labourers, my own ancestors that is, in the islands of the British Commonwealth. These are painful stories, but while Lin created sculptures of figures she called witnesses to that history, I saw that she, too, as the exhibition’s author, was a witness, and these figures, frightening though they were, turned a terrible story into one that one felt empathy for rather than pure horror or disdain. Credit and blame are, by dint of the presence of the witness, appropriately administered.

I had previously thought of Miller’s witness as vital in childhood, but Lin’s laying out—validating—of a brutal history and its resulting trauma was, for me, an example of the artist as an enlightened witness of history for descendants who carry in the fibre of their everyday lives the legacies of historical trauma. The validation of a witness supports children of history to rise above history, to not perpetuate on others the harms that had been visited upon them. “Witness, Oh Witness Dey!,“ the titular poem in my book, in conversation with Lin, is my offering, as witness, to the past and present lives of those of us whose ancestors were moved about, mostly involuntarily, by the imperial overseers.

SHR: Ancestry is so complicated, and ancestry tests are doubly so in their own ways with their racial categorizations and colonial apparatus. Talk to us about ancestry and inheritance, and how these themes flow through Oh Witness Dey!

SM: Recently, there has been an uptick in interest in the descendants of Indian indentured labourers taken by the British from India to their colonies to do the work that had been done in the days of slavery by Africans. Questions often asked are, exactly from where were we taken, and what is our relationship today to India.

I was once told, rather undiplomatically, by the son of an Indian diplomat, that people like me, the descendants of Indian indentured labourers are “bastardized Indians.” I was assured, also, by the wife of one of the Indian High Commissioners to Trinidad that, unlike Trinidadian Indians, they were never indentured. As well-meaning as the more academic questions of our Indianness, and about India, might be, they act to underline that we are not Indian. We may look Indian, but true Indianness was washed away on the waters of the Kala Pani. And that is sort of true.

I know I am Trinidadian, but race is alive and kicking in Trinidad, and although Trinidadians in general like to boast that all a we is one, people are painfully aware of their own and each other’s races. We mentally and socially cordon off ourselves from one another at times, the Africans here, the Indians there, the Chinese there, etc. But to those countries from which our ancestors came, we are not them. So what exactly are we?

If the academic interest is part of a movement to validate minority identity, it is a two-sided coin where the idea of exactly presses us to account not only for skin colour, but for historical injustices we did not ourselves initiate. When you can’t say where you come from, this might be interesting to an academic theorist or researcher, but it is a one-two punch in the stomach to the individual. An ancestry test employed by me is nothing but cheekiness, an act of art, that hints at something, not unlike a fortune teller, but gives me nothing, no street address, no town, no province from which to say my ancestors came. I came from nowhere, but surprise, I am 94% Indian. Nothing about Trinidad, naturally, and even more obviously, nothing about Ireland where I was born and of which I am a citizen whether I like it or not (I like it), and nothing about Canada where I have lived, worked, loved, and grown-up for over two-thirds of my lifetime.

As a pawn in one empire’s rule of much of the world, one cannot rely on scientific ancestry tests, to understand and state the reasons for one’s ancestors having been ripped up and scattered about, but one can search for ancestry, for the sake of art and poetry, in fields more reliable than science; for instance, in the spice trade of the 15 and 1600s, the lineage of ocean navigators, biblical, Aristotelian, and supposedly “scientific” notions about who is and isn’t human, about who has the right to own land, about what land belongs to whom, what language one should speak, books one learn from, and so forth.

SHR: We both love art: visual, sound, everything intertwined and in between. How does your practice as an artist inform your writing and vice versa?

SM: Although I always wrote, I had learned early that with words one was able to be explicit enough to cause trouble for oneself and for others. If I wanted to speak out, I realized, I had to find subtler ways than using words. As a result, for a long while my public speaking self was as a visual artist, employing two dimensional, and moving images. Visual art and video making allowed for hard-hitting declarations, but the framing, the use of sound, and other aesthetic choices always gave one the cover of ambiguity, and therefore safety.

At the same time, working as a visual artist taught me, among other things, that I must focus right in on my subject, know its boundaries, what its nuances are, and what straying, even a little, might do to a good idea. I learned to juggle images and ideas, how to soften while hitting, how to punch and block while softening, and also how, when, and why to use veiling as a tool. The conundrum with words, I rediscovered when I began to work more publicly with them, was their precision and explicitness. Words not meant, or not well-chosen were not only useless but could be dangerous. And while colour and framing, soundscapes and camera movements could act as a kind of sleight of hand that might turn a poorly conceived work into a thing of small beauty, misused words on the page were sure to drive an idea off the rails. If, as a writer, one wanted to be heard, understood, and believed, one could not afford to veil or blur the edges of an idea, nor, by the same token, to scream and shout. Words are less forgiving than the tools of the visual artist.

But here’s the catch: it is a kind of contradiction, and yet a truth, that in the writing of prose—not so much poetry—I do actually draw on my experience as a visual artist to help me figure out how to be explicit with words. The process starts with the confidence gained from experience that abstract ideas, thoughts, that is, can be made visual. It is always a matter of translation. Translating from the idea or thought to the visual—or more simply, to a picture, or pictures, in the mind—and then from those pictures to words on a page. It is long and slow, image by image, one word—no, not that one, for there is always a more precise one—punctuation, pictures in the head, a tangle of words and meaning unravelling and unspooling onto the page. Relying on the visual to help me with writing, I must pay attention to the minutest detail, like a filmmaker, or set designer who knows that the inclusion of, say, this cup instead of that one on a desk at the side of the protagonist will be read as a clue by the discerning viewer. If the cup is not meant to be a clue it is a bad inclusion in the scene, or if it is the wrong cup it can be a messy clue. Either way, the trust of the viewer will be lost.

Writing poetry, however, is more like making visual art. I find in poetry that how much one draws the curtain back and how much one veils, oftentimes is more immediate and revealing of one’s intentions than the same subject tackled in a piece of long prose.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Shani Mootoo was born in Ireland and raised in Trinidad. Mootoo’s highly acclaimed writing includes the novels Polar Vortex, Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab, Valmiki’s Daughter, He Drown She in the Sea, and Cereus Blooms at Night, as well as the poetry collections The Predicament of Or, Cane | Fire, and Oh Witness Dey! Her poetry has appeared in Wasafiri, Poetry Magazine, and Room Magazine. She has been awarded the degree of Doctor of Letters honoris causa from Western University, is a recipient of Lambda Literary’s James Duggins Outstanding Mid-Career Novelist Prize, and the Writers’ Trust Engel Findley Award. She lives in Southern Ontario, Canada.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji is the author of Port of Being. She received a 2023 Critic’s Desk Award from ARC Poetry magazine and was a finalist for the 2023 Alberta Magazine Awards. She lives in London, UK, and Vancouver, BC, where she is at work on a novel.