In Conversation: Angela Carr

“At first, writing was like singing, something I did for pleasure, and the compulsion came from deep inside, arising from the rhythms of the body.” —Angela Carr

A new season means new conversations, or, rather, new In Conversations! We talked to some of our Fall 2020 authors about their forthcoming books, and about the essential but frequently elusive art of writing. For the next couple of months, we’ll be sharing their wit, their wisdom, and their work with you on the blog. You can also subscribe to the Book*hug Press e-newsletter or follow us on social media—we’re partial to Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—for updates on upcoming author events. Happy fall, y’all.

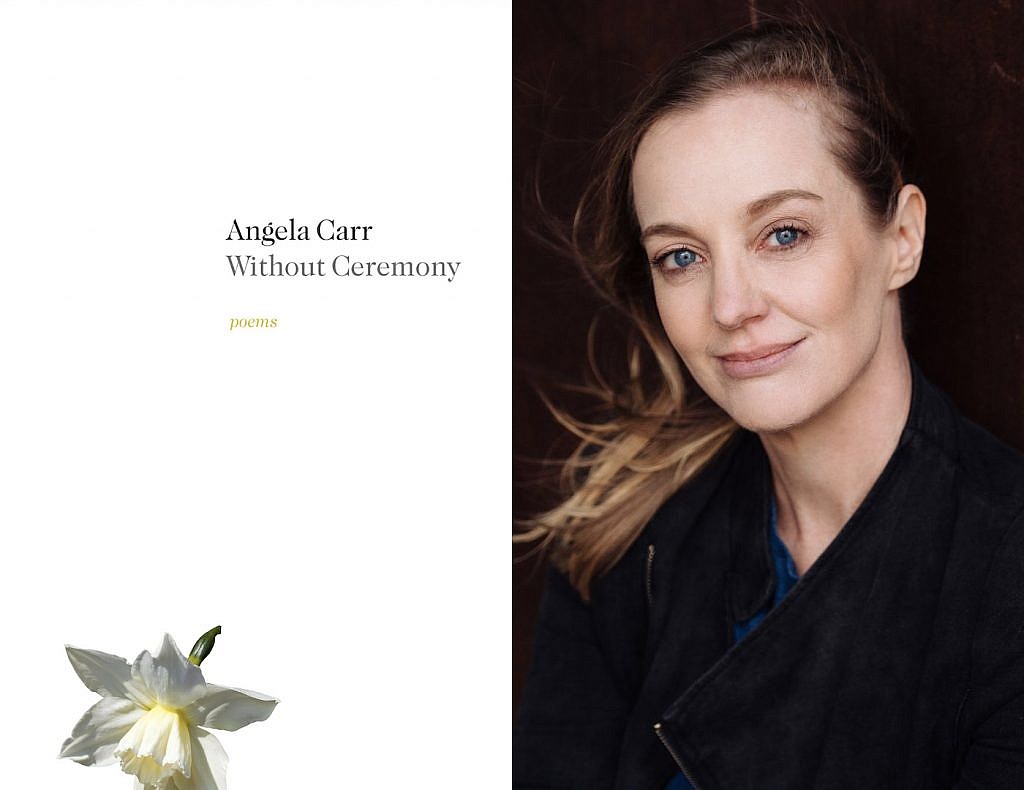

Our conversation continues with Angela Carr, whose poetry collection, Without Ceremony, celebrates its official publication today; congratulations! Centred on the everyday, and crafted without preamble or pretension, the poems in Without Ceremony are a literary pastiche—a thematic mosaic not unlike tracks on an album. Carr is no stranger to elegant understatement: her previous poetry collections, Here in There and The Rose Concordance, also commune with the subtler dark matter—stillness, fragment, abstraction—that sprawls around us. We talked to her about reading, writing, and the state of her wardrobe in quarantine; all equally important topics.

Describe your favourite article of clothing.

Every fall, I order wool socks from Schreters, a store on Boulevard Saint-Laurent, in Montréal, at the corner of Marianne. They are very thin wool socks so you can wear them with fine boots and still be warm. If you have ever lived through a Montréal winter, you know the difference between good and bad winter socks, because it’s truly dangerous to neglect this distinction (which I did for many years). The feeling in your toes could be lost forever. Maybe part of my spirit stayed in Montreal when I moved to New York, because my undergarment habits are all intact from that part of my life, as though my interior life is lost in time, anachronistic. In Montréal, I used my first cheque from poetry translation to purchase lingerie. I’ve added some emotional layers to my exterior, so I appear different on the outside, I blend in easily in New York.

An outer layer that I wear at work or the library when it’s chilly: a boiled wool “kimono” jacket that fastens with an oversized safety pin. It’s something Eileen Fisher made or remade, originally in the 90s, and I have it in black. It’s huge and soft. There’s something post-punk and shabby-chic about it that I love. There are other pieces I love, but since quarantine, I’ve been wearing mostly loose and comfortable clothing. I started wearing jogging pants for the first time, which are useful if you want to sit cross-legged at your desk. I can see that my partner is a little alarmed by my quarantine wardrobe. I’ve been trying to recruit her to the jogging pant uniform, so far without success. In fact, last week she ordered a pair of high-waisted black jeans for me from Rag and Bone, my favourite cut, cigarette leg, that I used to wear in pre-quarantine times. She says she ordered them because of a discount but I took it as a loving hint. It is easy to lose ourselves to the pandemic.

Where do you write?

Honestly, anywhere I can focus without interruptions is ideal, but that’s not the only way, because quiet is not always an option. I know that some writers travel around endlessly to formal retreats and residencies, but that has never been realistic for me or really desirable, to be honest; I have too many responsibilities — and pleasures — in my daily life. So how make space for writing amid the chaos of everyday life? It’s possible. Marianne Moore wrote the poems in Observations on a sofa in a studio apartment she shared with her mother. On his lunch breaks, Frank O’Hara wrote poems in which all the distracting stimulus of New York City is allowed to coexist, just as it does in everyday life. I’ve become an advocate of this type of writing; I like poetry that makes space for all the noise instead of trying to retreat from it and block it out. When Charles Dickens moved away from London, he complained about the quiet: he missed the noise and the chaos of the city. Now I live in New York City where there are a lot of interesting distractions and there’s not much private space. These days, when possible, I like to work in a library that recently re-opened (with restrictions) after being closed for six months due to the pandemic. It is the only place I work now, outside my apartment. Though I know the library may have to close again soon, in a second wave.

What book coming out this season can you not wait to read?

I just ordered Under the Dome: Walks with Paul Celan, by Jean Daive, translated by Rosemarie Waldrop. Also: Claudia Rankine’s new book, Just Us. I recently finished reading Phil Hall’s Niagara & Government, which is amazing.

What are you currently writing?

I’m currently writing a text about a translator named Cleo Archer. The name is partly inspired by Agnes Varda’s Cleo de 5 à 7, a film about a character who is waiting for biopsy results to learn whether her disease is terminal (the narrative takes place in a single day). Also, Cleo Archer’s initials, CA, are the reverse of my own, a concept inspired by Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, which I was reading during quarantine because it was Emily Dickinson’s favourite book (I was teaching an Emily Dickinson course at the time).

Why do you write?

At first, writing was like singing, something I did for pleasure, and the compulsion came from deep inside, arising from the rhythms of the body. I would not have told you when I was a kid that I would be “a writer.” Writing was not part of my identity, just something I loved and felt compelled to do. The identity part came later; it took me by surprise, it overtook me. I was raised to imagine my future in more practical terms than this. So, although I loved writing and had teachers who encouraged my writing early on, I never imagined myself becoming a writer. But despite the sense of practicality instilled in me by my family, I’m a hopeless romantic, which has kept me going through the more difficult periods in my writing life. If you want to be a writer, you need to be prepared to one day look around at the state of your unconventional life and know why you chose it, know with certainty that it has brought you more happiness than anything else could have. At first, it takes courage to make the decision to pursue writing, along with some foolish blind faith. Later, when others in your generation start to reap the financial benefits of their intelligent, measured, more conventional (more reasonable, they might say) life decisions, you need to know deep down that you wouldn’t trade your writerly life for anything. If you are not rich, you’ll have to be endlessly creative in the way you structure your life to make adequate time and space for writing. It’s a big commitment. Some people have managed to balance these needs (financial considerations versus time and space for writing) better than me. The writer’s life is not easy, but it’s endlessly interesting. And beautiful, too.

Describe the sky where you are.

Suddenly it is thick, unbroken cloud, dark, swollen with rain. I’m at the library so I had to step outside to see the sky. A few isolated drops falling. Elegant brick high rises appear shabby in such light. I notice a huge hole where townhouses stood a year ago, and worry the rain will start to pour as I walk under scaffolding. Across the street, a brick high rise built into or on top of an older brownstone. Pedestrians all in masks, except for one man with a baseball cap held over his nose and mouth, anxiously. Someone drives by playing Madonna through open windows, also wearing a mask. Now there will be tickets for those who don’t comply. They are shutting down areas of the city again.

I currently live on the twentieth floor of a high rise in Manhattan. What’s weird, though I am now used to it, is that you can’t hear the rain fall from this height. Our apartment is not spectacular but the view of the sky is stunning. It’s something like an “amphitheatre” view, which is an expression I first learned on a trip to the Greek island, Tinos, when we stayed in a cave house carved into a hillside with a panoramic view of the sea. In our high rise apartment, I feel like a bird in a nest. Resting on a branch of light (the sunlight is overwhelming bright). We should be moving soon, to an apartment with an entirely different sky view.

☙

Angela Carr is the author of three previous poetry collections, including Here in There (shortlisted for the A. M. Klein Prize for Poetry), The Rose Concordance, and Ropewalk (shortlisted for the McAuslan First Book Prize). Angela has also translated poetry books by Nicole Brossard (Ardour) and Chantal Neveu (Coït). She studied Creative Writing and Literature at Concordia University in Montreal, and later earned a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Montreal. She currently resides in New York City, where she teaches Literary Studies at the New School University.