Spring PREVIEW: Suzanne Leblanc’s The Thought House of Philippa, Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei & Ingrid Pam Dick

Multidisciplinary artist Suzanne Leblanc’s work occupies the space where philosophy and contemporary art converge. For several decades, her research, writings and visual art exhibitions have focused on the interconnectedness between philosophical forms and the artistic disciplines: how the architecture of human understanding informs creative endeavour.

In her acclaimed novel, The Thought House of Philippa (originally published as Le maison à penser de P. by La Peuplade in 2010, and now available from BookThug in a new English translation by Oana Avasilichioaei and Ingrid Pam Dick), Leblanc transposes a theory of individuality into a stunningly reflective, sensuous, and honest philosophical narrative.

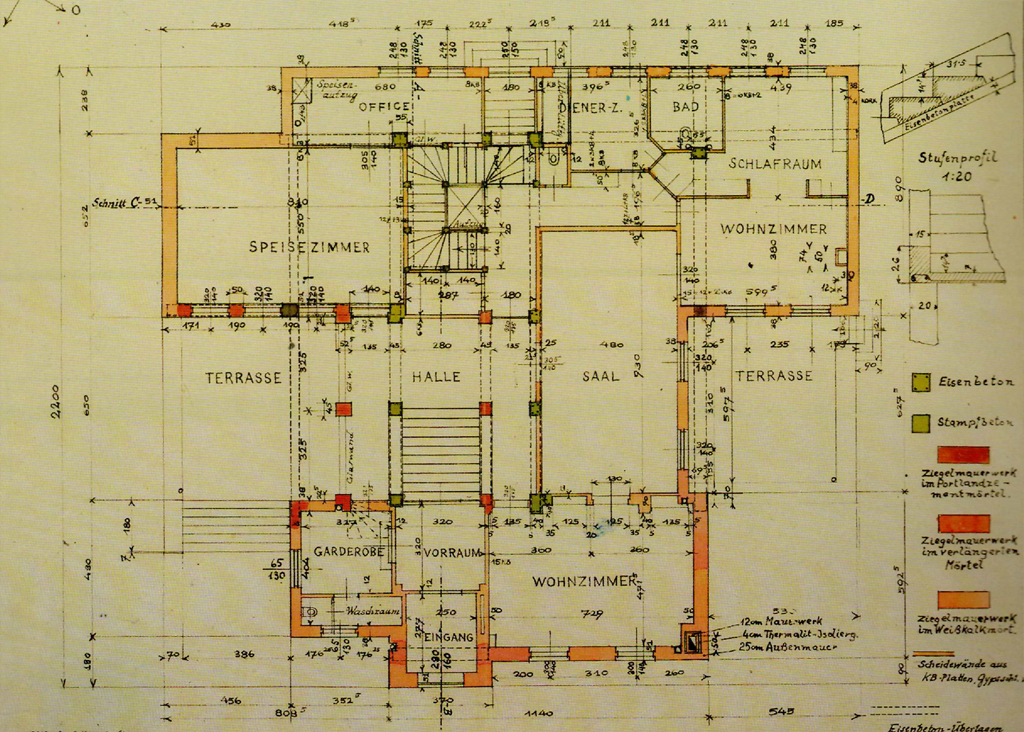

The titular “thought house” in the book is the famous Haus Wittgenstein in Vienna: the impressive modernist townhouse designed in part by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) for his sister Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein and her family. In 1925, Margaret invited her brother Ludwig to take part in the building project, in part to serve as a much-needed distraction after the rather disastrous end to his fascinating stint as a rural schoolteacher in Trattenbach, a small farming and factory village in the mountains south of Vienna.

Haus Wittgenstein, Vienna

Famously, Wittgenstein insisted that the luxurious townhouse meet his own rigorous specifications, spending years perfecting details like doorknobs and radiators, often quarrelling with the professional architects, and his family. When the house was nearly finished, according to one account, Wittgenstein insisted that a ceiling be raised 30 mm so the room would have the exact proportions he wanted. Of the resulting house, Ludwig’s eldest sister Hermine wrote: “Even though I admired the house very much, I always knew that I neither wanted to, nor could, live in it myself. It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me.” The house was completed in 1928.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Each section of The Thought House of Philippa (divided into chorales, foundations, phrases, and logics) corresponds with a specific room of the Haus Wittgenstein (although the philosopher-architect remains unnamed in the text). As the narrator Philippa (“P.”) ambulates through the house, the motion of her thoughts parallels her movement through the physical space — itself meticulously modelled after Wittgenstein’s floor plan. As her story unfolds, she moves from entrance hall to servants quarters to nursery, to the garden, and so on.

By spatializing Philippa’s internal ruminations, Leblanc harkens back to the famous ars memoriae: the broad canon of ancient and early modern texts interested in the spatial representation of ideas, and its relation to memory and comprehension. A standard trope in many of these treatises is the notion that human memory operates not unlike a physical space — a sort of storehouse — and that assigning things to their proper quarters inside an imagined physical space improves retention and recollection.

The Memory Palace of Robert Fludd

The Thought House of Philippa builds an architectural foundation for the main character’s intensely emotional and intellectually acute way of seeing the world and her place in it. Ideas crucial to Wittgenstein’s work — limit, freedom, interior and exterior, self and world – echo and shift in Leblanc’s precise, incantatory prose, propelled through the house’s architecture. The distinct voices of the novel’s four sections act as musical movements, constructed from repetition, variation and development of language, in alternating keys of austerity and splendour.

BookThug is proud to present The Thought of Philippa to an English-reading audience for the first time.

Praise for The Thought House of Philippa:

A unique and brilliant approach to the self, and to the intimate, as it creates and balances its own architecture of knowledge and emotion.

— Nicole Brossard

Attempts to make art with philosophical concepts continue to be treated with suspicion amongst those who insist that art be born in a burst, not composed stone by stone from ideas. What allows LeBlanc’s The Thought House of Philippa to succeed on its own terms lies in the elucidation of the propositions of its most prominent referent (Wittgenstein), while at the same time scraping against them. The result, oddly enough, is a firm yet soothing music. This is no mean feat. Same too for Dick and Avasilichioaei, the poet/translators of this edition, who deliver to English minds a text where (to enter squarely into Wittgenstein – if one dares to!) “What can be said at all can be [and is] said clearly.”

— Michael Turner, author of Hard Core Logo

The Toronto Launch of Suzanne Leblanc’s The Thought House of Philippa, Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei & Ingrid Pam Dick will take place May 15, 2015 @Videofag in Kensington Market (187 Augusta Avenue, Toronto, ON) 7:30-10:00 PM

For more information or to RSVP visit the event page, here.

❧

Excerpt from The Thought House of Philippa

By Suzanne Leblanc, translated by Oana Avasilichioaei & Ingrid Pam Dick

Available June 2, 2015, from BookThug

Chorale I

It was a house of which I knew nothing but the plans and several images. It had been constructed at the beginning of my century, the twentieth, in a city, Vienna, which proved decisive. This was well before I was born, by way of a philosopher whom I read at length, much later. His work had convinced me. I admired his life. The house was simple and austere, and I was rigorous and frank.

Pantry

Ground floor

Chorale II

This house drawn from the philosopher’s existence called up another in my own. I had reflected on the first while of the second I had forgotten everything. I linked an intellectual image to an emotive one. The connection was arbitrary. The philosopher’s work had convinced me, and I admired his life. The connection was singular. It contained a question and the discipline to traverse it.

East servant’s bedroom

Third floor

Chorale III

The house was a method. It was exact and simple. It was austere and obsessive. It issued from a life consecrated to the life of the mind. I cherished a neglected house. It was a house of the mind in which my method lived. I sought its coherence alongside that of the philosopher. His work was convincing, his life admirable. I sought, in the hallways of his house, my method, my mind.

Servant’s bedroom

Chorale IV

It was a singular house, and I sought a singular mind. Our encounter was arbitrary and yet coincident. In a sense I was its initiator, and it originated within the limits of my existence. In another sense the philosopher had originated a convincing work and had lived an admirable life. This encounter was at the foundation and at the conclusion of itself. Its artifact was primitive, emergent.

South servant’s bedroom

Second floor

Foundation I

One day, a very young child experienced indifference toward her parents and wanted to leave her family. Being obliged to sojourn there, she developed liminal, perilous and, frankly, psychologically acrobatic postures, in order to occupy the singular position that circumstances had forced on her.

The singularity extended beyond the family: it sufficed to be lodged there for one to feel this. Like a summit on which one had stood or a fold into which one had slid, making it possible to see what was not visible from anywhere else, her position demonstrated to P. to what extent the familial structure was accepted by its inhabitants, how this sketch of human organization also traced a limit whose infraction was only tolerated at the price of disgrace, bitterness, discredit—an unequivocal condemnation at best, a devouring feeling of culpability at worst. It seemed that the thought of this infraction, the idea of a life beyond this limit, was arduous: it sufficed to imagine a situation in which neither father nor mother were identified for one to recognize immediately the unavoidability of missing them. Against this background, hypotheses of afamilial socialist models, novel collectivist structures, radically alternative nourishing sketches were received with repulsion, as if it had been a question of dehumanized states that came from a future in which some exponential machination had outmanoeuvred her progenitors. So, no family at all, no humanity at all. From the summit, from the fold of her position, P. contemplated the full extent of her indifference.

Her vision outside the limits thus had to cohabitate with a life between walls. Yet it was equally necessary that she survive in the social territory, one region of which was constituted by her family—a different problem from the first, more formidable because more evasive. At the very least, this was the place where her mind was given back to herself, though within the family enclosure it had constantly been commandeered by the relationship of brute force inherent in all guardianship, albeit for her own good. In other words, neither father nor mother nor any master existed for her any longer, other than formally—none that P. hadn’t chosen and before whom she hadn’t considered herself, by the same token, an autodidact. It didn’t follow from this that the game had been played nor that, prior to this, her hand had been good and her bets, competent. It was even likely that this social game into which her family had transitively propelled her would prove all the more difficult, since she wasn’t certain she understood her role, or even whether she had one.

Additional impediments, therefore, these obligatory games where the best bets, those that are strategic and graceful, seem to proceed from real conviction, a consentedto immersion. Consequently, P. imagined a more general game than the one being played out immediately, a more natural role, more profound, of a cosmological scope, which earned her assent and from which she drew the impetus for her movements, actions, postures and even the feints in these human games in which she simultaneously found herself caught.

Entrance hall

Ground floor

Foundation II

Imagining a general game to motivate her role in the human games in which she was caught took priority in P.’s existence. This had a foundational cause, an originating event or, if one prefers, a primary motor, born of a mix of circumstances which, like the chemistry initiating life on a planet, owed the encounter of its congruent parts, the formation of its internal coherence, to chance. It was rather remarkable that this event occurred in the same place as her birth, a short interval later, on a terrain as if prepared to consummate the rupture which the initial detachment had commenced.

For ten days P. was removed from her father and mother, isolated from the family and kept in an unknown, clinical environment. The panic, despair, terror were seismic. Like a plate detaching from a matricial continent, P.’s life separated from that of her family—and she never again took it for granted. God required seven days to create the World, according to the Old Testament. P. required ten to lay the groundwork for her definitive universe. The latter was turned entirely toward Representation, whose figures and relations proliferated, like the minerals, flora, fauna and, after that, humankind in the biblical universe. A solitude arose, conscious of the external things she absolutely needed and which her representations sought to attain.

As a corollary, an autarchy emerged, establishing a singular regard that could no longer be “deconstituted.”

Governess’s bedroom

Third floor

❧

SUZANNE LEBLANC holds two PhD degrees, in philosophy (1983) and in visual arts (2004), and has been teaching since 2003 at the School of Visual Arts at the University of Laval (Quebec). She has exhibited multimedia installations in Quebec and has published theoretical works in Germany, France, Switzerland and Canada. Her research and creative work deal with philosophical forms inherent in artistic disciplines. She is currently leading a research-creation group on artistic strategies for the spatialization of knowledge. La maison à penser de P. (2010) is her first novel.

photo credit: Renée-Méthot

OANA AVASILICHIOAEI’S previous translations include Universal Bureau of Copyrights by Bertrand Laverdure (BookThug 2014), Wigrum by Daniel Canty (2013), The Islands by poet Louise Cotnoir (2011), and Occupational Sickness by Romanian poet Nichita Stănescu (2006). In 2013, she edited a feature on Quebec French writing in translation for Aufgabe (New York). She has also played in the bounds of translation and creation in a poetic collaboration with Erín Moure in Expeditions of a Chimæra (2009). Her most recent poetry collection is We, Beasts (2012; winner of the QWF’s A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry), and her audio work can be found on Pennsound. She lives in Montreal. Learn more about Avasilichioaei at www.oanalab.com.

photo credit: Anthony Burnham

INGRID PAM DICK (a.k.a. Gregoire Pam Dick, Mina Pam Dick, Jake Pam Dick et al.) is the author of Metaphysical Licks (BookThug 2014) and Delinquent (2009). Her writing has appeared in BOMB, frieze, The Brooklyn Rail, Aufgabe, EOAGH, Fence, Matrix, Open Letter, Poetry Is Dead, and elsewhere. Her philosophical work has appeared in a collection published by the International Wittgenstein Symposium. Also an artist and translator, Dick lives in New York City, where she is currently doing work that makes out and off with Büchner, Wedekind, Walser, and Michaux.

photo credit: Oana Avasilichoaei