Spring Fiction Preview: In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova, Translated by Sasha Dugdale

Friends of Book*hug, meet Spring 2021. Earlier this year, we unveiled the forthcoming titles in our Spring 2021 season, but now it’s time to get to know the authors and their books a bit better. For the next couple of months, we’ll be highlighting individual spring titles, and sharing some thoughts from the authors and exclusive excerpts on the blog.

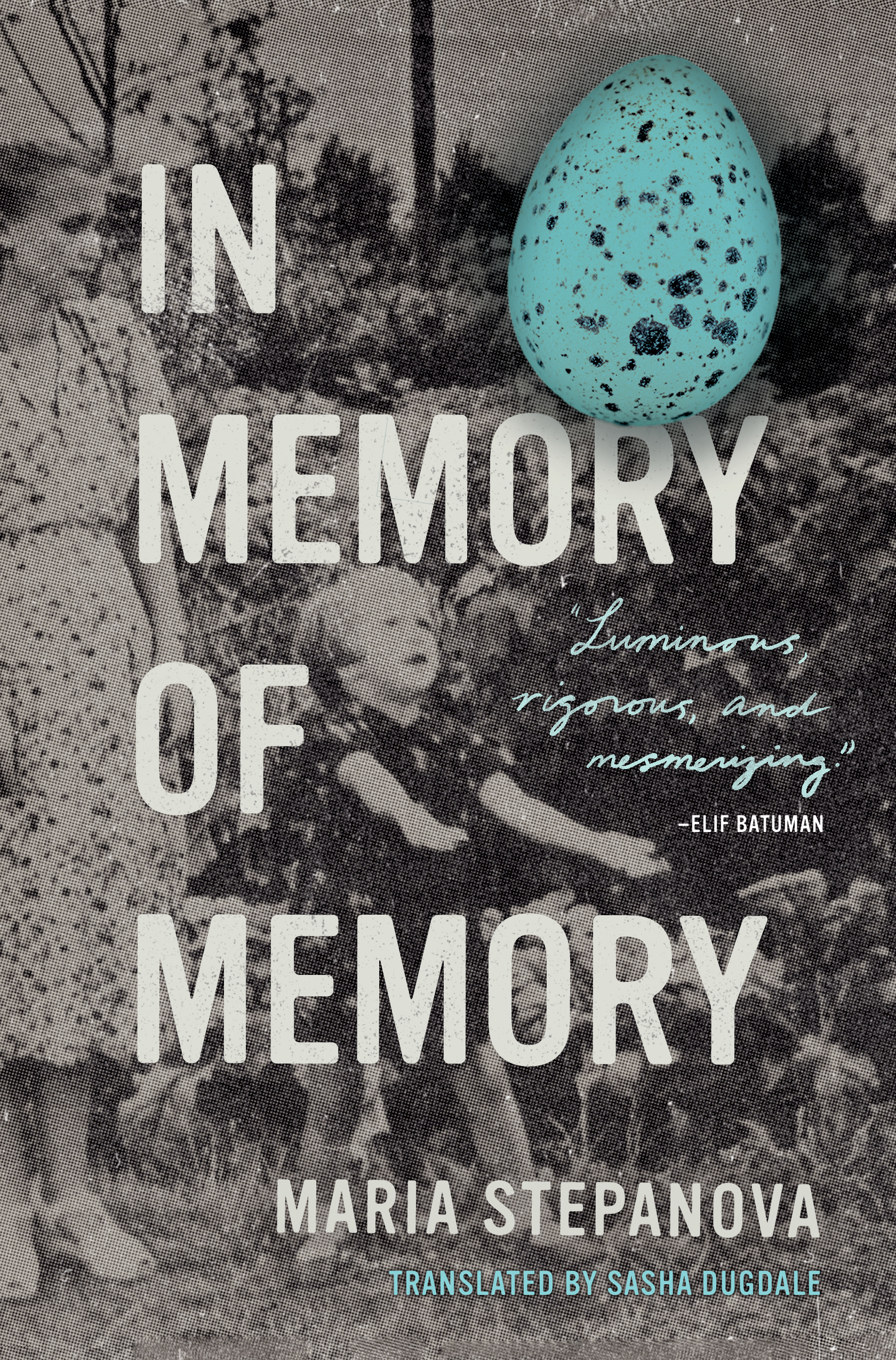

Today, we’re excited to preview Maria Stepanova’s award-winning novel, In Memory of Memory, translated from the Russian by Sasha Dugdale. Stepanova, “Russia’s next great writer,” is one of the most powerful and distinctive voices of Russia’s first post-Soviet literary generation. She’s received several Russian and international literary awards, including the Andrey Bely Prize and the Joseph Brodsky Fellowship, but in 2021—the “year of Stepanova,” according to The Guardian—English-language readers will finally be introduced: not just to Stepanova’s fiction, but to her poetry and essays, as well. In Memory of Memory’s English-language translator, Sasha Dugdale, is a force of nature in her own right: a poet and a playwright as well as a translator, she was recently shortlisted for the prestigious TS Eliot Prize, “the Prize most poets want to win.”

Don’t take our word for it; we’ll let Stepanova introduce herself:

Forthcoming from Book*hug Press on March 2nd, 2021, In Memory of Memory is imbued with rare intellectual curiosity and a wonderfully soft-spoken, poetic voice. In dialogue with writers like Roland Barthes, W. G. Sebald, Susan Sontag, and Osip Mandelstam, and dipping into various forms—essay, fiction, memoir, travelogue, and historical documents—Stepanova assembles a vast panorama of ideas and personalities and offers an entirely new and bold exploration of cultural and personal memory. In this book, an exciting contemporary Russian writer explores terra incognita: the still-living margins of history. Pulitzer Prize finalist Elif Batuman, author of The Idiot, calls In Memory of Memory “luminous, rigorous, and mesmerizing.”

As promised, we’ve selected an excerpt from In Memory of Memory, which you can read and enjoy below. The book is available now for pre-order in our online shop. Be sure to stay tuned for more exclusive, never-before-seen sneak peeks of our forthcoming titles.

For the interested reader, diaries and notebooks can be placed in two categories: in the first the text is intended to be official, manifest, aimed at a readership. The notebook becomes a training ground for the outward self, and, as in the case of the nineteenth-century artist and diarist Marie Bashkirtseff, an open declaration, an unending monologue, addressed to an invisible but sympathetic ear.

Still I’m fascinated by the other sort of diary, the working tool, the sort the writer-as-craftsperson keeps close at hand, of little apparent use to the outsider. Susan Sontag, who practised this art form for decades, said of her diary that it was “an instrument, a tool”—I’m not sure this is entirely apt. Sontag’s notebooks (and the notebooks of other writers) are not just for the storage of ideas, like nuts in squirrels’ cheeks, to be consumed later. Nor are they filled with quick outlines of events, to be recollected when needed. Notebooks are an essential daily activity for a certain type of person, loose-woven mesh on which they hang their clinging faith in reality and its continuing nature. Such texts have only one reader in mind, but this reader is utterly implicated. Break open a notebook at any point and be reminded of your own reality, because a notebook is a series of proofs that life has continuity and history, and (this is most important) that any point in your own past is still within your reach.

Sontag’s notebooks are filled with such proofs: lists of films she has seen, books she has read, words that have charmed her, the dried husks of completed endeavours—and these are largely limited to the notebooks; they almost never feed into her books or films or articles, they are neither the starting point, nor the underpinning for her public work. They are not intended as explanations for another reader (perhaps for the self, although they are scribbled down at such a pace that sometimes it’s hard to make out what is meant). Like a fridge, or, as it was once called, an ice house, a place where the fast-corrupting memory-product can be stored, a space for witness accounts and affirmations, or the material and outward signs of immaterial and elusive relations, to paraphrase Goncharov.

There is something faintly displeasing, if only in the excess of material, and I say this precisely because I am of the same disposition, and far too often my working notes seem to me to be heaped deadweight: ballast I would dearly love to be rid of, but what would be left of me then? In The Silent Woman, Janet Malcolm describes an interior that is, in some ways, the image of my own notebook (and this was a horrible realization). It is littered with newspapers, books, overflowing ashtrays, dusty Peruvian tat, unwashed dishes, empty pizza boxes, cans, flyers, books along the lines of Who’s Who, attempting to pass as real knowledge, and other objects passing as nothing at all, because they lost all resemblance to anything years ago. For Malcolm this living space is Borges’s Aleph, a “monstrous allegory of truth,” a gristly mass of crude fact and versions that never attained the clean order of history.

Maria Stepanova, born in Moscow in 1972, is one of the most powerful and distinctive voices of Russia’s first post-Soviet literary generation. An award-winning poet and prose writer, essayist, and journalist, Stepanova is the author of ten poetry collections and three books of essays. Her poems have been translated into numerous languages including English, Italian, German, French, and Hebrew. She has received several Russian and international literary awards, including the prestigious Andrey Bely Prize and Joseph Brodsky Fellowship. Her novel In Memory of Memory is a documentary novel that has been published in over 17 territories. It won the 2018 Bolshaya Kniga Award, an annual Russian literary prize presented for the best book of Russian prose, and the 2019 NOS Literature Prize. Stepanova is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of the online independent crowd-sourced journal Colta, which covers the cultural, social and political reality of contemporary Russia, reaching audiences of nearly a million visitors a month.

Poet, writer, and translator Sasha Dugdale was born in Sussex, England. She has published five collections of poems with Carcanet Press, most recently Deformations, shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize 2020, and an Observer Book of the Year 2020. She won the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem in 2016 and in 2017 she was awarded a Cholmondeley Prize for Poetry. She is former editor of Modern Poetry in Translation and is Poet-in-Residence at St John’s College, Cambridge (2018–2021).