Short Story Month Celebration: Alex Leslie

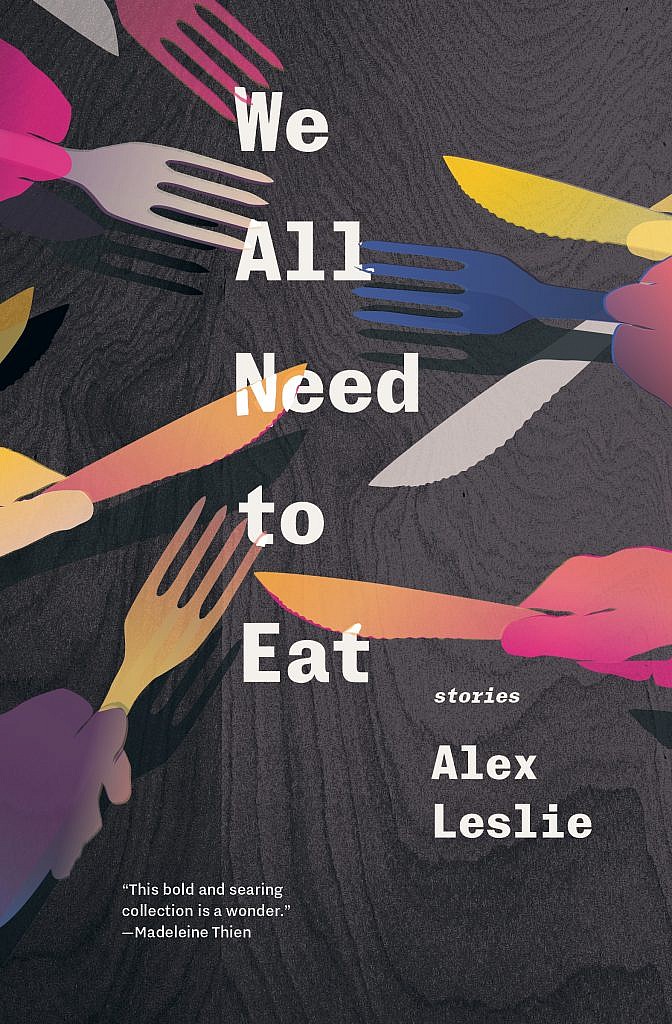

Our Short Story Month Celebration concludes today with Alex Leslie, author of We All Need to Eat.

This collection of linked stories revolve around Soma, a young Queer woman in Vancouver. Through thoughtful and probing narratives, the stories slipstream through Soma’s first three decades. Lyrical, gritty, and atmospheric, Soma’s stories refuse to shy away from the contradictions inherent to human experience, exploring one young person’s journey through mourning, escapism, and the search for nourishment.

We All Need to Eat has been nominated for several literary awards, including the Ethel Wilson Fiction Award, the Kobzar Book Award, and most recently, the Western Canada Jewish Book Awards. In praise of the collection, Scotiabank Giller Prize-winning author Madeleine Thien writes, “This bold and searing collection is a wonder.” Kirkus Reviews calls the book “a magnetic collection that must be read over and over,” and Broken Pencil adds, “We All Need to Eat is a work of precision.”

Today we’re pleased to share an excerpt from “The Sandwich Artist,” a story from the collection.

The Sandwich Artist

My father always told me, “if anything terrible happens, treat yourself to a nice meal.” Advice passed on from one generation to another, a recipe for a history of starvation, but I didn’t know that yet. I only knew Chinese five spice BBQ pork with pineapple and red glaze, fish and chips bundled in greasy newspaper, corned beef boiled in bags, rotisserie chickens leaking orange condensed steam over tinfoil. I knew sweet and sauced and salty and, later on, spiked. I knew broiled and fat ’n’ happy. I knew how to drink a bad day out of a gravy boat. It isn’t that I’ll run out, it’s that in the beginning there was never enough.

When my brother hadn’t left the house for three weeks, my father called me up and said, “Hey, I bought a Heritage Farms chicken, want to come over?”

“How’s Josiah?”

“We’ll need a lot of garlic, right?”

“A lemon,” I said. “Is he any better?”

“Yeah, he seems better. What else.”

“Rosemary.”

“Dried.”

“I’ll bring some from my pots.”

“Bring extra so I’ll have some in the fridge. I have wine,” he said.

“Fresh garlic.”

My father never bought fresh spices, just endlessly replenished the giant containers of powdered garlic, onion, and oregano from the bulk bin at Real Canadian Superstore. The containers lined the top of the family stove, unmoving as gravestones. The garlic was the texture of instant milk and smelled like chicken soup mix. Its scent flavoured my childhood memories of camping trips, burgers laced with its rank tang. When I started to cook for us, after my mother left, I walked to the grocery stores and asked a white-aproned man restacking the peaches where I could find the garlic. “I don’t know what it looks like,” I told him. He looked at me like I was playing a prank. At home, I scraped at the sheer white outer tissue, then sliced the whole bulb down the middle and hacked bits out with the point of a steak knife, flung the massacred pulp into the pan, juice stinging my eyes. Now, my fingers dismantle garlic instinctively. I press a knife’s blunt side to a clove with the flat of my palm to loosen the casing, and the smooth white clove falls free, its side fingernail-smooth.

“My garlic not good enough for you?” he growls.

“We need lots of olive oil for the skin. You got enough?”

He’s always running out of something.

“I have lots of oil, just bought a new can.” I wince. He buys his olive oil in bulk too, in a giant can with spout, like an emergency gasoline supply.

“Tell Josiah I’m coming.”

“He knows.”

My roast chicken is perfect. If you know how to make one thing perfectly, you will always get invited back. It’s your basic French roast chicken. Remove the neck from the cavity, keep it for the jus. Halved lemons and salt and crushed peppercorns and a few garlic cloves fisted into the belly, stretch the skin over the neck hole, pin it in place with a skewer. Massage the chicken with oil, coat the skin with rock salt and cracked pepper. Not table salt; the flavour is french-fry sharp. Use salt with enough substance to cook in the oil. Yogourt makes the skin brown and thick, but I prefer the crunch of oil, salt, pepper. Bacon fat if you want smoke. 375 oven until it browns, then 350 with a tent of oil over it. Thirty minutes to the pound.

Baste often.

(Save 25% off all short story collections from Book*hug Press, including We All Need to Eat, until May 31. Please follow along all month as we celebrate short stories by sharing excerpts and readings on the Book*hug Blog. Follow us as well on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.)

Alex Leslie was born and lives in Vancouver. She is the author of two short story collections, We All Need to Eat, a finalist for the 2019 Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and People Who Disappear, which was shortlisted for the 2013 Lambda Literary Award for Debut Fiction and a 2013 ReLit Award. She is also the author of the prose poetry collection, The things I heard about you (2014), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Robert Kroetsch Award for innovative poetry. Alex’s writing has been included in the Journey Prize Anthology, The Best of Canadian Poetry in English, and in a special issue of Granta spotlighting Canadian writing, co-edited by Madeleine Thien and Catherine Leroux. She has received a CBC Literary Award, a Gold National Magazine Award, and the 2015 Dayne Ogilvie Prize for LGBTQ Emerging Writers.