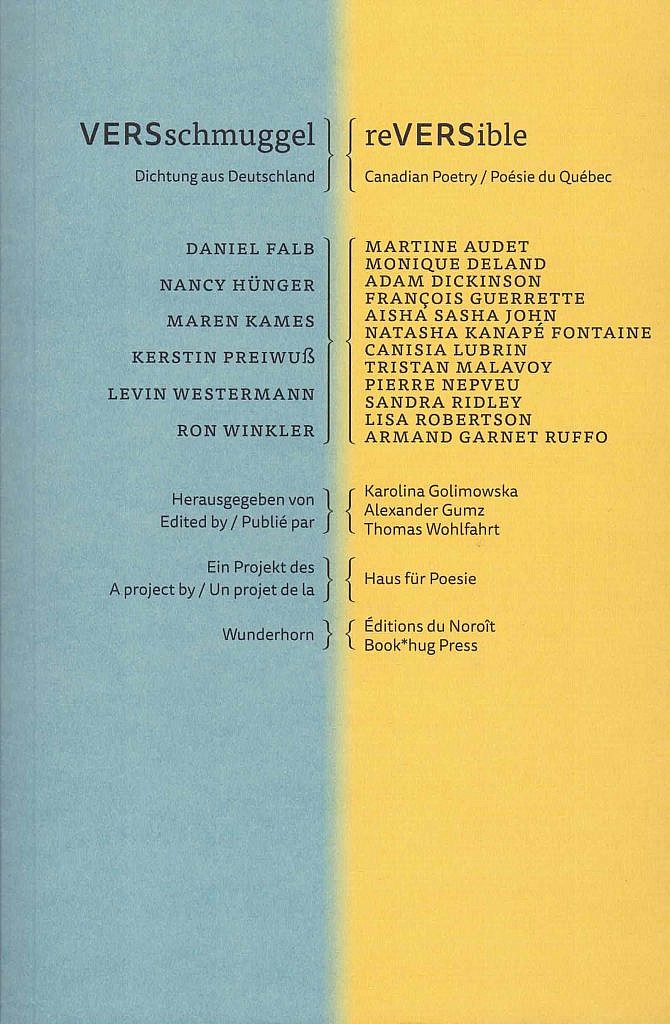

Presenting VERSschmuggel / reVERSible: An Anthology of English Canadian Poetry / Poésie du Québec / Dichtung aus Deutschland

Today, Book*hug Press is excited to present VERSschmuggel / reVERSible: An Anthology of English Canadian Poetry / Poésie du Québec / Dichtung aus Deutschland and a roundtable-style interview with some of the contributors.

VERSschmuggel is a poetry translation project hosted by Berlin’s Haus für Poesie. This unique international collaboration and cultural exchange between poets includes three main components. First, a group of poets are invited to Berlin to participate in a week-long translation workshop during which they share work and translate each other’s poems into their respective languages. Following the workshop, the poets join one another on stage for an evening performance at the annual Poesiefestival Berlin. All of this work eventually culminates in the publication of a multilingual anthology that showcases the workshopped poems, both in their original and translated versions, which is where we come in. More on this soon…

In recognition of Canada’s role as Guest of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the focus of 2020’s VERSschmuggel project was on poetry from Canada. And so, in June 2020, six German poets virtually met twelve Canadian poets, six writing in French and six writing in English, including:

English

Adam Dickinson | Aisha Sasha John | Canisia Lubrin | Sandra Ridley | Lisa Robertson | Armand Garnet Ruffo

French

Martine Audet | Monique Deland | François Guerrette | Natasha Kanapé Fontaine | Tristan Malavoy | Pierre Nepveu

German

Daniel Falb | Nancy Hünger | Martin Kames | Kerstin Preiwuß | Levin Westermann | Ron Winkler

Due to the pandemic, the eighteen participating poets were unable to gather in person in Berlin for the translation workshop, as was originally planned. Instead, they met over Zoom, “smuggling” their poems across linguistic borders. The poets worked with all three languages—English, French, and German—reading, discussing, and translating one another’s poems. At the end of the workshop, the poets participated in a virtual event hosted by Poesiefestival Berlin. The event, which was streamed on June 6, 2020, can be watched below:

The corresponding intimacy that carried across the virtual space is noticeable in the resulting publication, VERSschmuggel / reVERSible: An Anthology of English Canadian Poetry / Poésie du Québec / Dichtung aus Deutschland. This trilingual edition was co-published by Book*hug Press (English Canada), Éditions du Noroît (French Canada), and Das Wunderhorn (Germany), in collaboration with the Haus für Poesie. We became involved after meeting with representatives from the Haus für Poesie at the 2019 Frankfurt Book Fair. We were immediately enticed by everything about this project—the coming together of poets, the cultural exchange of ideas and language, the act of translation, and so much more—and we readily agreed to sign on as one of the anthology’s co-publishers. It’s been an exciting project, from start to finish, despite the many challenges we all faced as a result of the pandemic. We’re delighted to share this expansive anthology with all of you today.

To celebrate the release of reVERSible, we talked to some of the Canadian English-language participants—poets Adam Dickinson, Sandra Ridley (Silvija, The Counting House), and Lisa Robertson (The Apothecary, The Men, Nilling)—about their experiences working on both the reVERSible / VERSschmuggel translation project and the resulting reVERSible/VERSschmuggel anthology. We’re honoured to share their responses below.

What stood out to you or surprised you about being part of the reVERSible project, both with regard to the translation workshop in June 2020 and the publication of the resulting anthology?

Adam Dickinson: I was really energized by the translation workshops. I was surprised by how much translation felt like a form of writing. These poems were not my own, yet I was giving them a life in English, I was sculpting them and editing them in an effort to transport them or smuggle them into a new linguistic field. The work of translation felt as playful and as creatively generative as writing my own poems (when the writing is going well, that is). I also love how relentlessly trilingual the anthology is. The French, German, and English come at you with all their beauty and intensity.

Sandra Ridley: The seamless ease we had in sliding into “the work” of working with each other’s work. We seemed to be kindreds in the midst of chaos. And collaborating lifted me.

Lisa Robertson: This was my first ever experience translating German, which I only ever briefly studied in high-school, 45 years ago. So it was a very good thing that a pre-translation gloss was made. In the publication, I really enjoyed everyone’s short notes or statements on translation.

“We seemed to be kindreds in the midst of chaos.” —Sandra Ridley

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the translation workshop in June 2020 was hosted online, over Zoom. Can you talk about the experience of participating in the workshop virtually?

Adam Dickinson: Working on translations over Zoom with Daniel Falb and François Guerrette was an intimate and transformative experience. The early, disorienting days of the pandemic were swirling around us while we focused our attention on precise turns of phrase, the relative merits of synonyms, and the physiological effects of punctuation. Our meetings were long, but the time flew by. I felt dialed-in and freed from the pandemic for a moment, as though working by candlelight or with flashlights in a tent deep in the woods. Anneke Lubkowitz and Roland Glasser provided navigational assistance between languages, offering opportunities for playful and provocative mistakes. We had fun as we explored each other’s work. Our conversations were opportunities to learn how to inhabit each other’s poems with our own tongues and ears. Eventually, for me, it felt like the poems were conjuring their own version of English, a version bent by my experience of camping out for a while in their linguistic forests and back alleys.

Sandra Ridley: There was urgency and intensity. We slipped into each other’s worlds, not just into the poems. A different kind of immersion would have happened in Berlin. The pandemic meant that instead of a brief time together in person, we met online for hours and hours over several weeks and became as thick as thieves.

Lisa Robertson: I did not work on Zoom. I used email to do our work together. The reason is that back then—it was the beginning of Zoom, remember?—there were very poor security protocols in place generally speaking, and shortly before the translation workshop began, I was doing a different Zoom reading for an American university, and the event was Zoombombed with a criminally violent video. I was too affected by that to risk another Zoom contact just a couple of weeks later. Honestly, I was very sad to not be able to go to Berlin and enjoy one another’s company in the setting of that city. We all did our best under the circumstances.

“Our conversations were opportunities to learn how to inhabit each other’s poems with our own tongues and ears. Eventually… it felt like the poems were conjuring their own version of English.” —Adam Dickinson

How can we incorporate translation into our daily lives?

Adam Dickinson: My recent writing incorporates scientific data, so I often find myself thinking about how to “translate” microbiological or toxicological data into poetry. Translating between domains of knowledge and scales of observation and information is already part of my daily poetic practice because I think of metabolic processes (both bodily and global) as forms of writing (hormones, for example, are a mode of mass communication). More generally, I think moving between languages attunes one to the generative potential of less obvious forms of translation. One could argue that art itself enacts translation by provoking us to look at things in unfamiliar ways.

Sandra Ridley: As I write these answers, Selina Boan’s first book of poetry, Undoing Hours, sits beside me—a beautiful ache of a book. I mention this because I’m thinking of a word in it that she repeats, and it’s one that I didn’t know. It’s a Cree word. Nohtâwiy. I hadn’t encountered it before. The easiest and most disrespectful thing would have been to gloss over it.

With translation… with being… we have to want to do the work. I hope that learning fuels change. There is so much work—and reparation and healing—that we need to do.

How can we incorporate translation? By mindful listening, fearless curiosity, and respectful play. What would our world be like if we could encourage/enact/experience more of all of this?

As I look back, the reVERSible project was an incredibly rewarding experience.

Lisa Robertson: By moving out of our domestic language/s. Since I moved to France from Vancouver, I translate daily. Also though, and more practically speaking, by insisting on reading often and at length in unfamiliar languages. The point is to construct a relationship with another language, not to master it, or even “know” it.

“The point is to construct a relationship with another language, not to master it, or even ‘know’ it.” —Lisa Robertson

—

reVERSible is available to order from our online shop, or from Knife Fork Book.

The reVERSible / VERSschmuggel translation project is supported by the Government of Canada, the Ministère des Relations internationales et de la Francophonie du Québec, the Embassy of Canada, and the Vertretung der Regierung von Québec in Deutschland.