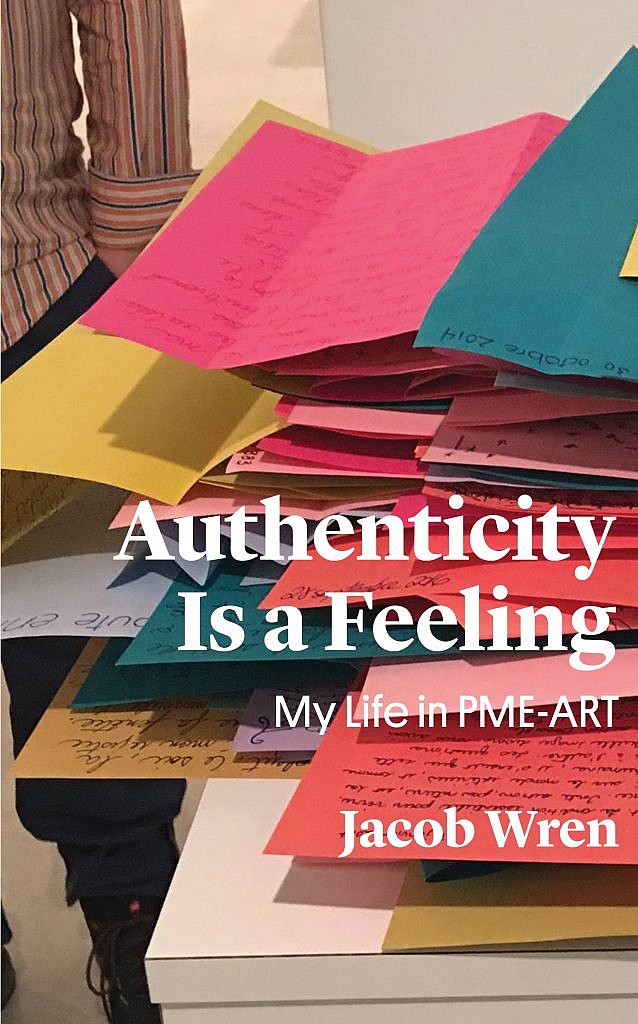

Feature Friday: Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART by Jacob Wren

In this week’s edition of Feature Friday, we are excited to bring you an excerpt from Jacob Wren’s Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART, a compelling hybrid of history, memoir, and performance theory. Written, among other things, to celebrate PME-ART’s twentieth anniversary, the book begins when Jacob Wren meets Sylvie Lachance and Richard Ducharme, moves from Toronto to Montreal to make just one project, but instead ends up spending the next twenty years creating an eccentric, often bilingual, art.

Author of The Gift, Barbara Browning, writes that Jacob, “Investigates the possibility of “being oneself in a performance situation” – including the performance of this beautiful, quiet, vulnerable book.” Praising PME-ART, Brian Parks in The Village Voice adds, “PME-ART interrogates the idea of the performance itself. But it never fails to be that performance, and a damn good one. God bless Canada.”

It is a book about being unable to learn French yet nonetheless remaining Co-Artistic Director of a French-speaking performance group, about the Spinal Tap-like adventures of being continuously on tour, about the rewards and difficulties of intensive collaborations, about making performances that break the mold and confronting the repercussions of doing so.

We hope you enjoy this excerpt from Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART. Happy reading!

From Authenticity is a Feeling:

Gaétan Nadeau has a peanut allergy of the life-threatening variety. When we performed Families Are Formed Through Copulation in Prague, he carried around a scrap of paper that explained his condition in Czech, to show waiters in restaurants as he ordered. About two hours before our second show, Gaétan sat down next to me in the lobby of the Divadlo Archa. He was having difficulty breathing and turning a bright shade of red. He had eaten some Thai food (apparently with peanuts) a few hours ago and the reaction was kicking in hard. He had the injection in his pocket and self-administered it, inserting the needle through his jeans into his leg, while we waited for the ambulance. As we waited, we debated whether there was any way he could be back in time for the show at 8 p.m., whether we should cancel, or what our other options might be. It was decided that I’d fill in for Gaétan, holding the script in my hand, doing my best to follow along with the staging and choreography. (An echo of replacing Mads back in Bergen during my first trip to Europe.)

Performing in Families Are Formed Through Copulation for the first time that night, as a last-minute replacement, I had new insights into what was bothering me about the show. It was like a machine in which you had to follow the text, lighting, and movement, like a conveyer belt carrying me along from section to section without respite. I didn’t feel anywhere near the same freedom I sometimes felt performing the previous two shows, freedom to improvise at times, adjust the pacing as we went, say something unexpected, or break the structure and then effortlessly return to it. Some of this was because I was only filling in, and didn’t know the show well enough to fully play within it. Also, I was literally holding the script in my hand, following along with it page by page. But I don’t think it was only that. The script, the narrative aspects of the script, the storytelling aspects, and the way we had organized them to alternate with performance actions, made the structure much harder to pull away from. It was tight rather than loose, a quality greatly admired in most theatre, but apparently not by me.

It was also one of the worst audiences we have ever performed for, consisting primarily of a school group of international students who texted, sniggered, made unpleasant noises, talked (only to be hushed by one of their teachers), and generally misbehaved from the first minute to the last. They were especially amused during moments when I seemed confused, when I wasn’t sure what happened next, when I paused, unsure where to go or how long I should take to get there, and either Tracy or Laure had to give me the necessary hints in order to keep the show rolling. Mathieu Chartrand, our technical director, said listening to me speak the text changed his understanding of it. My delivery was considerably more ironic than Gaétan’s. Mathieu said I had a way of speaking the text in which it sometimes meant almost the exact opposite of what it literally said.

The next day Sylvie went to pick up Gaétan at the hospital. She was talking with the nurse when the doctor arrived and, since the doctor spoke English well, Sylvie thought it would be all right to leave Gaétan there while she organized the insurance payment for his stay. But then the nurse looked more closely at Gaétan’s chart, followed by an examination of the plate from the lunch he had just eaten. It was clear something was wrong; she was rapidly speaking to the doctor in Czech and gesturing at the chart and then to the plate. Gaétan had gone to the hospital with a peanut allergy and, the next day, they had served him peanuts for lunch. (There’s a reason Kafka comes from Prague.) Because he was still on the antiallergen drugs, he hadn’t felt any negative reaction from what he had just eaten. But if he had left the hospital without realizing what had happened, the drugs would have worn off around 8 p.m. (the exact time he was meant to be onstage performing) and, with the peanuts still in his system, there is a possibility he might have died. It was only because the nurse and doctor noticed in time, before he left the hospital, that this calamity was avoided and Gaétan was back in time to perform our third and final show in Prague.

*

When I’m onstage, I sometimes think about the degree to which my way of being onstage has been influenced by Tracy Wright. I have never told anyone this. The stillness, the care, the precision and anger and irony. Tracy died on June 22, 2010, just six and a half months after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. When I first heard the news I was on tour with An Anthology of Optimism in Italy. We were just about to perform in a former sports stadium in Polverigi. The next day we were invited to lunch at someone’s house. From the large balcony I looked out at one of the most beautiful landscapes I had ever seen in my life, endless green rolling hills, and thought there was no possible way to reconcile such an idyllic setting with such completely fucked-up news. (Strangely, she died the day before my birthday.) I wouldn’t make it back in time for the funeral, and later also missed her memorial service.

I worked with Tracy for fifteen years. We made at least nine shows together. We were on tour for many, many years. I’ve never worked with a better performer or a better artist. She is also one of the few artists PME worked with who is absolutely and unquestionably as stubborn as we are. This is the first time I’ve written about her since she died.

+ + + +

One of my clearest memories. We were walking down the street in Montreal, in the middle of rehearsals, making yet another show together, I don’t remember which one, when she asked me why we were doing this, or why I was doing all this, what was the point of making all these shows, since it was often so difficult. Why were we doing it?

Without missing a beat, I said: “Just killing time before my eventual and inevitable suicide.” It was a joke but, at the same time, one of the more honest things I’ve ever said. Now, when I think back on the exchange, I regret being so flippant. It is such a clear memory because it is a moment, an utterance, I so clearly regret. I wish I had said something more inspiring. Over the years I have tried my best not to take my depression out on other people, but that was a moment I remember when I used it as a club. “Oh, is that all,” she replied. Each word precisely withering in that way only Tracy could be.

I don’t think it’s any secret that much of my life is taken up in a struggle with depression. And yet, more and more, I’m not even sure depression is the right word. Melancholy, despair, sadness, self-sabotage, mourning for myself and for the world. It might have been during that same conversation, or it might have been a different one. But I remember Tracy saying to me that she had so many more reasons than me to be depressed, her life was more fucked up, she dealt with so much sexism in her work life, while I got away with murder in that way straight white male artists so effortlessly seem to do without even noticing it. Nonetheless, she had to admit, though she had so many more reasons to be, I was clearly the more depressed one. I think I just silently agreed. At any rate, I don’t remember what I said in response.

❧

Order your copy of Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART here.

Jacob Wren makes literature, performances and exhibitions. His books include: Unrehearsed Beauty, Families Are Formed Through Copulation, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed, and Polyamorous Love Song (a finalist for the 2013 Fence Modern Prize in Prose and the 2016 ReLit Award for Fiction, and was named one of The Globe and Mail’s 100 Best Books of 2014). His most recent novel Rich and Poor, was a finalist for the 2016 Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction. As Co-Artistic Director of Montreal-based interdisciplinary group PME-ART he has co-created the performances En français comme en anglais, it’s easy to criticize, Individualism Was a Mistake, The DJ Who Gave Too Much Information and Every Song I’ve Ever Written. He travels internationally with alarming frequency and frequently writes about contemporary art. Connect with him on his blog (www.radicalcut.blogspot.com) or on Twitter @everySongIveEve.

Jacob Wren makes literature, performances and exhibitions. His books include: Unrehearsed Beauty, Families Are Formed Through Copulation, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed, and Polyamorous Love Song (a finalist for the 2013 Fence Modern Prize in Prose and the 2016 ReLit Award for Fiction, and was named one of The Globe and Mail’s 100 Best Books of 2014). His most recent novel Rich and Poor, was a finalist for the 2016 Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction. As Co-Artistic Director of Montreal-based interdisciplinary group PME-ART he has co-created the performances En français comme en anglais, it’s easy to criticize, Individualism Was a Mistake, The DJ Who Gave Too Much Information and Every Song I’ve Ever Written. He travels internationally with alarming frequency and frequently writes about contemporary art. Connect with him on his blog (www.radicalcut.blogspot.com) or on Twitter @everySongIveEve.