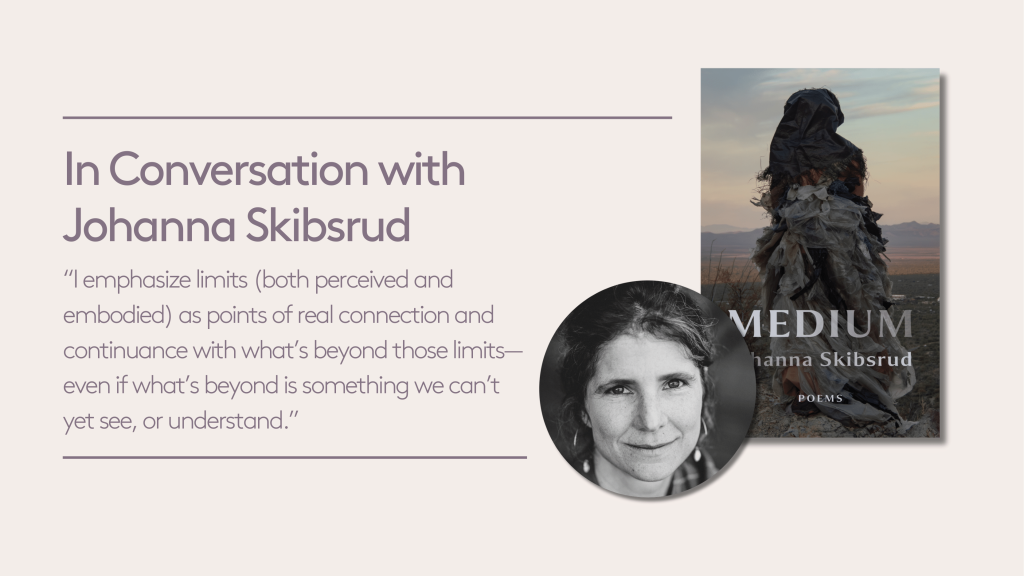

Limits as Points of Real Connection: In Conversation with Johanna Skibsrud

Join us today in welcoming our guest Johanna Skibsrud, author of Medium! Johanna sits down with Beatriz Hausner, author of She Who Lies Above, to answer some questions about her newest poetry collection.

BH: You note, in the Preface, that Medium began and evolved over a period experienced as pregnancies, childbearing, and parenting, wisely equating life-giving as a mediumistic state particular to women. Inherent in gestation, bearing and giving birth to life, is the notion of existing inside time. How do you relate the mediumistic process to time and its passing? Is the mediumistic state limited by time? Is it finite? Is it infinite?

JS: Thank you for this question, because I’ve been thinking about the role and structure of the medium in spatial and material terms, primarily—in terms of the processes of connection and transmission between two otherwise seemingly disparate points. But I’ve also wanted, very particularly with this collection, to tap into poetry’s prophetic mode—its link to more ancient forms of conjuring and spell-making. With this project, as with other ongoing work, I try to emphasize limits (both perceived and embodied) as points of real connection and continuance with what’s beyond those limits—even if what’s beyond is something we can’t yet see, or understand. So, I guess I would say, in answer to this question, that the mediumistic state is not limited by, but rather a way of participating in, time. And, as such, it’s both finite and a way of touching upon the infinite.

BH: The troubadours, as you point out, invented the form where the reasons (razos), the vital conditions that give way to their poems, or songs (cansos) of love are separated, made distinct one from the other, thereby creating a kind of dialectic tension between the two ways of being inside their poetic experience. How do you see the energies in the vidas of the women portraited in Medium inform and define the poetics you’ve created to accompany them?

JS: My goal for this book was, pretty specifically, to find a way of articulating the tension you describe here so beautifully while, at the same, not seeming to compartmentalize or isolate what’s valuable and generative within lyric expression from its vital condition. I wanted the poems to seem just as continuous and/or co-extensive with the vidas as they are a departure from their more grounded and linear narrative structure. The vidas introduce the possibility of their own rupture or opening—and then the poems speak from and within the space of that opening. A big part of the revision process for me was to try to find a balance between the abstracting and universalizing potential of the lyric “I” with the particulars of both its historical and material context. I hope that what I’ve achieved in the end is a collection of voices that both speak from and respond to the grounded (but, hopefully, as you suggest, still energetic) particulars of their personal and historical conditions and frame.

BH: I am in awe of your talent at merging the intellectual, the conceptual, even, with the lyric. Ideas obviously interest you, as does the possibility of developing a poetics, a unique language (voices, cadences, rhythms, and forms) that somehow echo those ideas. Can you comment?

JS: This observation is meaningful to me because I don’t tend to think of concepts and/or the acts of thinking and being as separate from their language of expression. Ideas and words and sense and sound seem absolutely co-extensive to me—like the condition of having a “voice” and the frameworks that give rise to that condition. This is a big part of why I really revere the poetic form. Poetry has such a capacity for not only demonstrating but also exploring and developing this essential relation, giving rise to new forms and modes of thought, new relationships and ways of being.

BH: How would you describe the place, the juncture you find yourself in, interiorly and externally, as a poet?

JS: I hope that I’m at the very beginning of something. For years, I’ve been thinking about the relationship between poetry understood as a language-based art form and as a mode of thought, a creative potential for making. Right now, I’m working on a follow-up project to my critical study, The Poetic Imperative: A Speculative Aesthetics (published my McGill Queens in 2020), that I’m tentatively calling The Poetic Imperative: A Study in Practice—because I see the new project as a follow-up (and maybe even a form of protest or rebuttal) to my earlier, more “speculative” approach. I’ve challenged myself to find and to make active or living examples of poetry at work in the world—to observe its various trajectories, and impacts, and real potentials. In the process (so far) I’ve run into a lot of seeming impasses in terms of both getting the work made and illustrating (sharing) the connections I intend. At the same time, though, it’s exciting to engage with poetry in this way…off the page, and in forms that aren’t, maybe, easily recognized as poetry, but that nonetheless—through the poetic activation of unfamiliar relationships between “subject” and “object,” “I” and “Other”—allow us to read and pay attention to the world around us more responsively.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Johanna Skibsrud is the author of three previous collections of poetry, three novels—including the Scotiabank Giller Prize–winning novel, The Sentimentalists—and three nonfiction titles, including The Nothing That Is: Essays on Art, Literature, and Being, and most recently, Fool: A Study in Literature and Practice. An Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of Arizona, Johanna divides her time between Tucson, Arizona, and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Beatriz Hausner was born in Chile and immigrated to Canada with her family when she was a teenager. She has published many poetry books, including The Wardrobe Mistress (2004), Sew Him Up (2010), Enter the Raccoon (2012), and Beloved Revolutionary Sweetheart (2020). Her prose and poetry have been published in many chapbooks and included in several anthologies, and her books have been published internationally and translated into several languages, including her native Spanish, French, Dutch, and Greek. She is an active participant in the international surrealist movement, and a respected historian and translator of Latin American surrealism. Hausner, who is trilingual, served three terms as President of the Literary Translators’ Association of Canada and was Chair of the Public Lending Right Commission. She was also a founding publisher of Quattro Books. Hausner lives in Toronto where she publishes The Philosophical Egg.