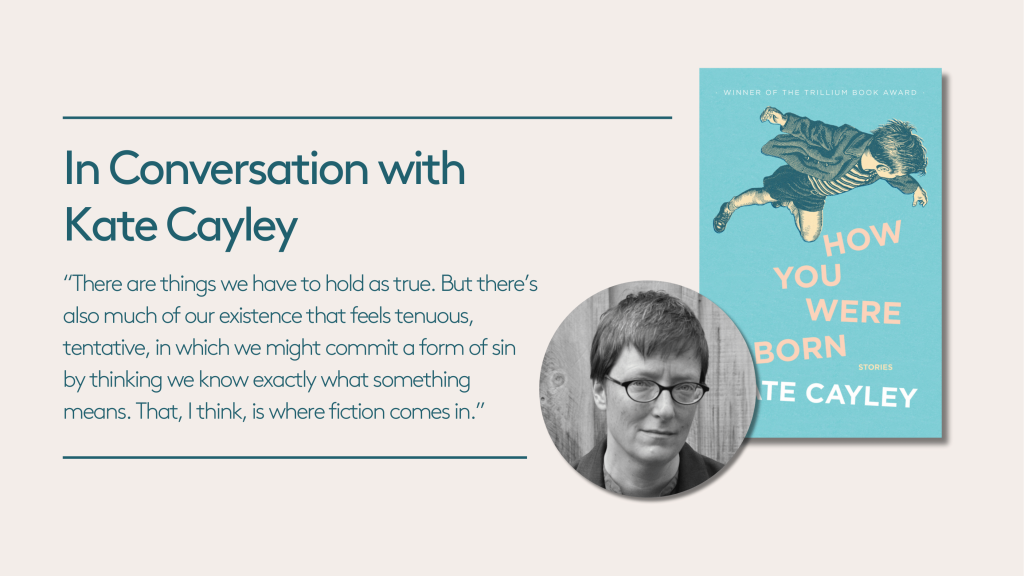

“Where Fiction Comes In”: In Conversation with Kate Cayley

Today, Kate Cayley sits down with Alayna Munce to discuss the tenth-anniversary edition of her award-winning short story collection How You Were Born.

AM: What kinds of things did you find yourself re-working in the original stories for this edition, and do you feel like those revisions had more to do with your craft developing over the 10-year interim, or about your perspective as a person changing? Or is that a false dichotomy?

KC: I don’t know if it’s a false dichotomy, but I definitely feel more convinced of change than of development, much as I’d like to believe in it. Sometimes it feels like I know less than I did when I was beginning to write, or at least that I’m hampered by a more sophisticated self-awareness, comparing myself to others and to my own past. I’m not sure whether this is an effect of the internet being a self-consciousness machine, or just the experience of aging. That aside, these revisions felt like an opportunity to fix things that had been nagging at me for ten years in the weirdest way. Tiny, tiny things no one would notice. Places where I’d clipped a sentence too short or taken out a necessary comma or added an unnecessary one. It was really fun to indulge that part of myself, all the small shifts in focus that I hope brought the stories a little further along.

AM: Do you see any generalizable differences between the original stories and the three new stories?

KC: I was putting together this collection at the same time as working on a new one (unfinished as yet) and it was really interesting to try to compose stories that would fit into How You Were Born. They had to be short (I’ve grown longer-winded, it seems, over the last decade!), they had to fit in thematically with the original book, and yet I wanted them to also feel like a bit of a departure, like they stretched the boundaries rather than slurring into a mood. I hope they have. An especially nice thing, which I discuss in the preface, is getting another crack at the third story about the queer couple, Molly and Robin, and their young daughter, and Molly’s relationship to an old woman with dementia who lives in the neighbourhood. This was, I think, one of the first stories I ever wrote, before I became a parent myself. I put it away for years, unable to make it work, but remained defensively fond of it, even though I knew it wasn’t working, my tendency (at the time) to sparseness tipping into opacity: the story wasn’t letting the reader in. But I carried it around, wrote and rewrote it, and kept hoping it could find a home. I never thought it would be with the two stories connected to it.

AM: Do you have a favourite story from this collection? Or some moment you feel particularly tender toward? Or is that like asking you to pick a favourite child??

KC: Hmmm. I’m really fond of “Young Hennerly,” maybe because of finding a recording from the library of congress of an old woman singing the song of the title. It was beautiful and terrifying, and I wanted to find an imaginative home for it. Which this story became.

AM: In the foreword I wrote for this edition, I reference a conversation you and I had recently about moral fiction, in which you quoted Brandon Taylor quoting D.H. Lawrence about the need for restraint on the part of the writer. The conversation came back to me when I was preparing to write the foreword, because it struck me as I read and re-read the stories, that there is a powerful moral impulse in much of your writing, along with a great restraint. Can you say more about how you grapple with moral questions in your fiction?

KC: I can’t seem to help grappling with them, I guess. But I hope I’m coming at it slant, which seems important in fiction, one of the only things art is good for, morally speaking. It can express itself ambivalently, without closing down in a conclusion, which seems more and more important to me with every passing year. In my life, which includes my life in which I hope to be politically attentive, at least a bit, there are some things I feel no ambivalence about. There are things we have to hold as true. But there’s also so much of our existence that feels tenuous, tentative, in which we might commit a form of sin by thinking we know exactly what something means. That, I think, is where fiction comes in. Events and people can retain an inexplicable quality that seems morally significant. I read a piece recently by the critic Julian Lucas in which he (paraphrasing a theorist whose name I haven’t successfully retained) says “opacity is the foundation of ethics,” and I was very struck by this. That there is something moral in keeping a distance from meaning, in evading final meaning. Which is where the restraint comes in. This also feels like the distinction (which is really important right now!) between politics and ideology. Politics, I hope, just means giving a flexible attention to what is. There is nothing that is truly apolitical. But ideology (of the left or the right) feels more like knowing what a thing is, even prior to the muddle of experience. Which makes art impossible, or reduces it to a strategy or an educational tool rather than a force in and of itself.

AM: There were a lot of things I really enjoyed in your preface to this new edition, and one was the passage where you talked about how you see the short story as a form, especially the bit about the short story as a form with some humility in relation to the reader. You write about the modest amount of time it takes from the reader, how it can slip unobtrusively into the cracks of a life, how it “can be a small yet quietly transformative thing, like an unexpected conversation with a stranger.” I wonder if this quality of humility might also be related to the restraint with regard to morality discussed above? What do you think?

KC: Yes, definitely. That and failure. Everything I’ve ever done that I felt succeeded, even a little bit, had to teeter on the edge of failure. And I like the humility of the short story especially right now, because we’re all engaged in this weird attention economy in which everyone is afraid of being unrecognized, unseen, that someone else is more seen than they are, and this leads us all to grandiose claims, or the hazard of them. That art will “transform” or “revolutionize” or something else that sounds great, but seems dangerously close to advertising. The smallness of the short story feels like a domestic possibility, the way a poem is, a small claim not a large one. Which might resist economies.

AM: What short story writers do you read most avidly, both in an enduring way, and lately?

KC: In no particular order: Yiyun Li, Brandon Taylor (I really want to recommend “Prophets,” which I think so far has only appeared in Joyland and which is the epitome of a morally ambiguous story), Lisa Moore, Lorrie Moore, Rebecca Curtis (her reading of “The Christmas Miracle” is what I go to when I want to laugh and cry very hard without feeling like an idiot, the story is that good), Edward P. Jones, Alice Munro, George Saunders, Yukio Mishima (terrible views, brilliant writer), Tessa Hadley, Carmen Maria Machado, Gogol, Kafka, Alexander McLeod, Kelly Link, ZZ Packer, Mavis Gallant, David Bezmozgis, and Andre Alexis.

AM: Are there any questions you’ve been dying to be asked about this book?

KC: I think you’ve asked them. Thank you.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Kate Cayley is the author of three poetry collections, including Lent, a young adult novel, and two short story collections. How You Were Born won the of the Trillium Book Award and was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction. She has won the O. Henry Short Story Prize, the Mitchell Prize for Faith and Poetry, and the Geoffrey Bilson Award for Historical Fiction. She has been a finalist for the K. M. Hunter Award, the Carter V. Cooper Short Story Prize, and the Firecracker Award for Fiction, and longlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize and the CBC Literary Prizes in both poetry and fiction. Cayley’s plays have been produced in Canada, the US and the UK, and she is a frequent collaborator with immersive company Zuppa Theatre. Cayley lives in Toronto with her wife and their three children.

Alayna Munce is the publisher and a member of the editorial collective at Brick Books. Her first novel, When I Was Young and in My Prime (Nightwood Editions, 2005) was nominated for the Trillium Book Award and appeared on the national bestseller list. Alayna has also worked as a freelance fiction editor. She lives in the Parkdale neighbourhood of Tkaronto/Toronto in a bustling household of six, and is slowly at work on a new novel.