“The narrative of heroism is continually bent”: In Conversation with Gail Scott

Gail Scott’s Permanent Revolution, a collection of new essays gathered alongside a recreation of her groundbreaking text, Spaces Like Stairs, was recently named a finalist for Le Grand Prix du livre de Montréal 2021. To quote the awards jury, Gail Scott is a “véritable icône of Montreal’s literary scene… Her work is both humourous and érudite and her attention to the material aspect of language creates a spiral of thinking that is absolutely captivating, a spiral calling for Permanent Revolutions, as the title suggests, for Scott is not afraid to re-actualize her propositions. Radical and constantly curious, the intelligence at work in this collection of texts offering, as soon as one starts to read, an experience of resolute jouissance.”

In celebration of her nomination, we asked Scott some questions about this genre-defying collection. With characteristic wit and a mesmerizing grasp of language—all the ways in which it sinks and folds into politics—Scott shared some thoughts on literary/feminine “excess,” her use of the elusive + sign, and the ways French-language writing has influenced her artistic practice. Read on for all of this and more.

B*H: Many of the essays in Permanent Revolution comment on your past novels: Obituary, Heroine, My Paris. In a sense, they spill out of past works; revisit, reframe, and elaborate past politics. Are these essays experiments in excess? Writing which exceeds/cannot be contained within its initial form?

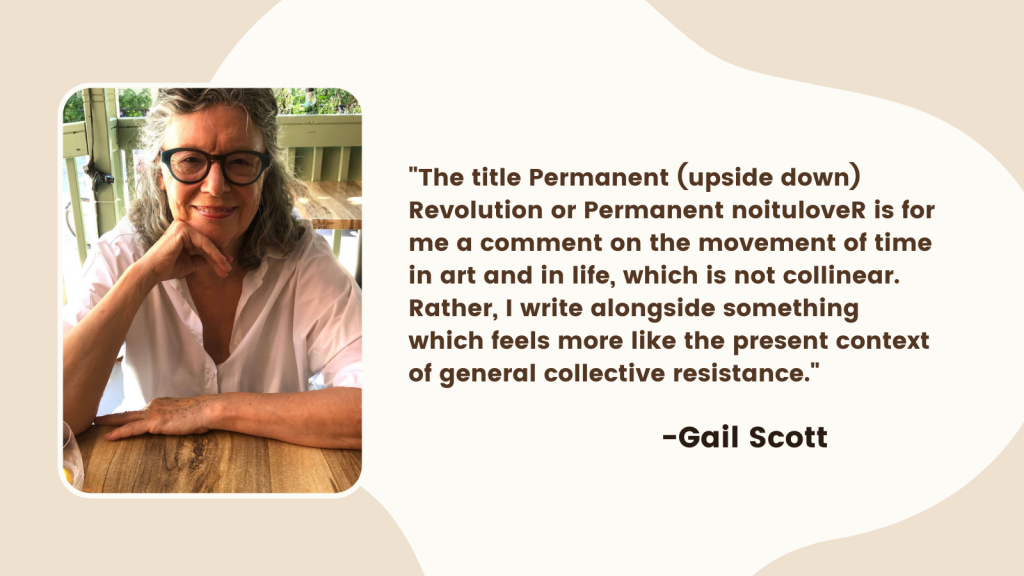

GS: I do see the notion of excess as something bursting to be expressed in the present moment, but which, for reasons that are often political or social, is still beyond our language horizon. However, I am absolutely not focused on reframing my own past efforts. If the cores of some new essays in ‘The Smell of Fish’ section issue from thoughts expressed upon the writing of each novel, this core material is woven into current considerations. The title Permanent (upside down) Revolution or Permanent noituloveR is for me a comment on the movement of time in art and in life, which is not collinear. Rather, I write alongside something which feels more like the present context of general collective resistance. To write is to be part of an interaction with many energy vectors, which is why time is less forward than moving as in a field of wildflowers. When I look at the paintings of Hilma af Klint (painted a century ago!), in the opening essay, called Excess, I am striving to discover what I read as a notion of the féminine that leaks in now-time from the jumble of geometric pastel abstractions–something in excess of language that is not yet named.

B*H: Does the identity of the writing subject change throughout these essays?

GS: I do have an ever ongoing reconsideration of my relationship to the word feminine. Or at least of how the word works in writing. In itself, the word still appears to me to be disastrously bounded, even if the external manifestations of that bounded-ness have differed over the generations As I say in the book, the feminine is something I often admire or desire in others but what is it? Furthermore, too often feminism has been portrayed as focused on the heteronormative feminine. What about lesbians? What about transwomen? The answer lies in thinking of the writing itself as the subject of the work (and not individual identity questing). But reading and writing the moment means language constantly modifies in the dialogue of the one with the many. For instance, the tragedy of the assassination of one young Black man calls up the deaths of the many remembered in the Black Lives Matter or Indigenous movements of resistance. The instances of death referenced do not function as new signs; they provide rather electric shocks running through our current and perpetually ongoing consciousness of a perpetual state of emergency foisted on minorities.

B*H: Can you share some thoughts on the significance of the “+” symbol in place of “and” throughout the book?

GS: The + sign signals the notion of ‘and’ as cumulative and absorbative. Again, I think of the communal relations of things in the architecture of a field as opposed to the architecture of an arc.

B*H: Did writing and editing this book at the height of the pandemic have any effect on its structure or language?

Yes! Isolation makes one feel weirdly unbounded, and since I live alone I was able to muster tremendous focus. This allowed me to find a shape for the essays both erudite and playfully anecdotal. But it is important to note I was not in many ways alone. There was an ongoing good conversation with my editor Margaret Christakos and with books and with memories and zoom readings by poets I adore from all over the continent.

B*H: You are a writer “who wants to write with French in her ear to frame her own culture from a certain critical distance,” disrupting an Anglo-dominant context. You also speak of productive literary exchanges with various Franco-Canadian writers and members of the Theory, a Sunday group. Are Franco interlocutors crucial to your creative process?

Certainly. I live in Québec! Apart from a certain gallic sonority in my sentences, spoken and written, what has drifted into my work from French-language writing is the desire to make language think in fiction—and to find it useful to let the thinking appear on the surface of the tale. Living among Francophone writers helped me realize, very early on, that theory is not something necessarily academic. It can also arise from collective interaction—and activism!—and thus be a part of how one sees that everyday life which is fundamental to writing a novel.

B*H: What draws you to the idea of the “heroine,” with its connotations of heroism, nobility, or sympathy?

Not much. My so-called heroines may struggle heroically but their little private revolutions are full of almost comic (hence abject) hairpin curves. The narrative of heroism is continually bent.

❧