The Modern Self is a Reader Self: In Conversation with Bertrand Laverdure and Oana Avasilichioaei

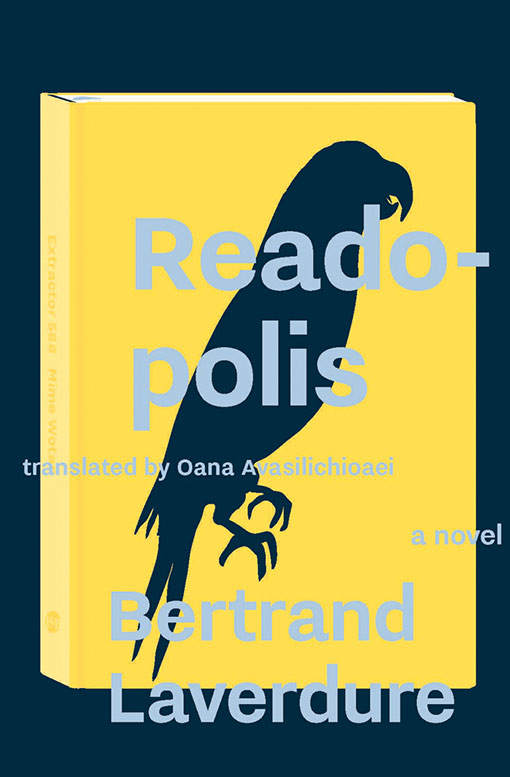

Bertrand Laverdure’s novel, Readopolis, translated by Oana Avasilichioaei, playfully examines the idea that human beings are more connected by their reading abilities than by anything else. Originally published in French as Lectodôme (Le Quartanier, 2008), the novel was critically-acclaimed and was a finalist for the 2009 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault. A review in Le Devoir called the book, “Brilliant, playful, perfectly convincing, Lectodôme has everything to place Laverdure in the ranks of the ‘sickest literary greats.’”

BookThug intern Shayanna Seymour recently sat down with Bertrand and Oana to discuss the process of translating the novel into English, and more.

Shayanna Seymour: How did you decide on Readopolis as a title and what might an alternate title be?

Bertrand Laverdure: In French, the title is Lectodôme, in part a reference to David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, and also simply a dome, an architectural form. In a way, like Cronenberg’s film, my book is a kind of bizarre response to the invasion of a new form of technology of communication (in the film, it’s a reflection on the power of TV), the social network, the web, and a philosophical essay disguised as a character-driven story about our natural, networked mind. A dome is at the same time a religious metaphor and a beautifully crafted form. It’s made from many concentric circles, akin to radio waves pulsing into the sky and Wi-Fi in our houses. A dome is like emissions of waves stuck in an elegant shape. Readopolis is a book about communities of readers all around the world and in a way, about the idea that to read and talk about what we have read is connected to our ability to distribute waves, circles and responses all over our network. The French title is more metaphoric; the English one is easier to grasp and a great find by my translator.

Oana Avasilichioaei: I think Readopolis comes across somewhat metaphorically in English as well, due to the fact that it is an invented word, and readers are prompted to imagine what it might mean. The suffix polis, which has given us words such as metropolis and acropolis, was a city state in Ancient Greece, particularly one that would be philosophically considered in its ideal form. As such, a polis of readers speaks to Bertrand’s idea of a community of readers that are connected and who form a sort of network. “Readopolis” also considers what such a world/state/community might look like both philosophically as a concept and physically as enacted by people in an urban context. I also wish to mention that I am indebted to the translation’s first reader, Ingrid Pam Dick, for this title’s formulation. Our conversations were instrumental to helping me reimagine the novel’s title in English.

SS: What’s one thing you want readers to know about Readopolis?

BL: All things change so quickly and swiftly that we are unable, quite often, to take a moment and think about what we experience as readers, thinkers and writers. Every six months, something is updated somewhere; every two years, there’s a new technology, a new app, a new super product that swipes clean our old way of life, that changes our way of thinking. We are living in what is probably the most exciting and most disturbing period of modern history. Art, literature, technology are slowly merging into some kind of exponential potential that reshapes our knowledge of what is art and literature. Readopolis is a novel in which I try to address these questions in different ways. Readopolis is an essay disguised as a novel, a novel disguised as a bizarre play, and a play disguised as a desire to understand our modern consciousness. To read is to be naturally updated. To read is to network efficiently in a world that evolves quickly. The modern self is a reader self. Readopolis develops these ideas in novel form.

OA: Readopolis is also very anchored in Montreal and in Quebec literature (while also going beyond these sites) and as such offers an inside view into a literary and reading tradition that is still very little known to English readers in Canada.

SS: What impact did working with Bertrand Laverdure have on your style as a literary translator?

OA: Every book one translates is an opportunity to place oneself in the imaginary world of the writer and in a way, inside their creative process of composing the work. It is the most intimate and closest form of reading that I know. And also a great privilege. As such, translating gives me an in-depth and physically embodied understanding of how other writers write and has most likely contributed to my restlessness and constant curiosity in form and made me a more versatile writer.

SS: Was there any difference in procedure between writing/translating Universal Bureau of Copyrights and Readopolis?

BL: Certainly, it was more difficult for Oana to translate Readopolis because there are a lot of style shifts in the book. Universal Bureau of Copyrights was more or less the work of one narrative voice.

OA: One of the most interesting aspects of working on Readopolis was the fact that, due to its many voices and forms, I had to reinvent these many voices and forms in English. So it was compelling to rethink how the epistolary sections, Socratic dialogue or screenplay, for example, could be expressed in English, sometimes vis-à-vis the ways that these forms have historically existed in English. The challenge with Universal Bureau of Copyrights was that it is a work of speculative fiction, which is not an area with which I am greatly familiar, so finding its speculative voice (and in a way my own as well) involved several drafts of revision. It felt almost like making a sculpture in layers; with each layer, you chip away at it a bit more until you end up with the sculpture itself.

SS: What do you think is the most important thing to do when translating between two languages?

OA: One of the most important things to realize about translation is that one doesn’t translate between two (or more) languages only, but also between two (or more) cultural specificities, histories, geographies, ways of being in and relating to language, ways of understanding through the particularities of the languages, etc. So I need to be aware of this as a translator and develop strategies that can account for these aspects in some way.

How long did it take you to complete writing/ translating Readopolis? Were there any obstacles?

BL: Oana is an exceptional translator and I’m so respectful of her work that I just responded to her few and precise questions. It’s so easy to work with her because it’s always easy to work with talented people. I am honoured to have been translated by a sensible poet who is also a translator. Working with Oana is a great pleasure.

OA: I am grateful to Bertrand for his kind words here and also, of course, for answering my questions and helping gain further insight into the work. Being able to discuss certain aspects of a book with the writer can make the task easier at times. I translated Readopolis over an intensive period of about four to five months, which included writing an initial draft, revising the entire translation, getting feedback from an initial reader and making more revisions, and receiving feedback from the copyeditor and coming up with the final draft.

SS: What books are you currently reading?

BL: I’m currently reading a lot of books at the same time: Les Adieux by René Lapierre (a great contemporary French-Quebecois poet); Un Long Soir by Paul Kawczak (a great first book of poetry form a new voice); Correspondence by Albert Camus and Rene Char (I’m a fan of letters exchanged by great writers); City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara by Brad Gooch (research for my next novel that will be a kind of literary fiction about the life of O’Hara).

OA: I also always read many books at once, usually across various genres. Most of my current reading has to do with research for my next two main projects (a hybrid work of poetry and a libretto for an opera): A Book of the Book edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay (a classic collection of essay on what constitutes “the book” which I am revisiting); Le son comme arme by Juliette Voleter (essays on how sound has been used as weapon); Spit Temple, the Selected Performances of Cecilia Vicuña edited and translated by Rosa Alcalá; The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin; Sonic Somatic: Performances of the Unsound Body by Christof Migone (essays about sound art); So We Have Been Given Time Or by Sawako Nakayasu (a work that is both poetry and theatre all at once).

❧

I’m resting.

Dozing off. Doing nothing, just resting.

All I want is to lie in bed, arms out like a cross, left cheek on the pillow, legs and chest flat on the mattress. I haven’t read anything today and won’t read anything before one in the afternoon. I am a reader—what publishing houses call “a member of the editorial board.”Yet there is no editorial board, no summit meeting, no secret gathering to formulate impartial, obvious decisions, ones that are democratic and positive. I am a reader because I have my own view of literature: what it should be; what buttons to sew on a novel’s sleeves; what zippers to place throughout a narrative; the ideal length of writers’ detestable pipe dreams.

—From Readopolis

Order your own copy of Readopolis here.

Bertrand Laverdure is a poet, novelist, and the current Poet Laureate for Montreal (2015–17). A prolific writer, Laverdure is the author of three books of poetry and four novels, including Lectodôme (2008), Bureau universel des copyrights (2011; published in English by BookThug as Universal Bureau of Copyrights in 2014), and La chambre Neptune (2016). He has won many awards for his work, including the 2003 Grand Prix du Festival International de Poésie de Trois-Rivières, and was a finalist for the 2009 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for Lectodôme.

Montreal-based writer, translator, and editor Oana Avasilichioaei has published five poetry collections, including Expeditions of a Chimæra (with Erín Moure; 2009), We, Beasts (2012; winner of the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry from the Quebec Writers’ Federation) and Limbinal (2015). Previous translations include Bertrand Laverdure’s Universal Bureau of Copyrights (2014; shortlisted for the 2015 ReLit Awards), Suzanne Leblanc’s The Thought House of Philippa (co-translated with Ingrid Pam Dick; 2015), and Daniel Canty’s Wigrum(2013).

Coit by Chantal Neveu, translated by Angela Carr

Coit by Chantal Neveu, translated by Angela Carr