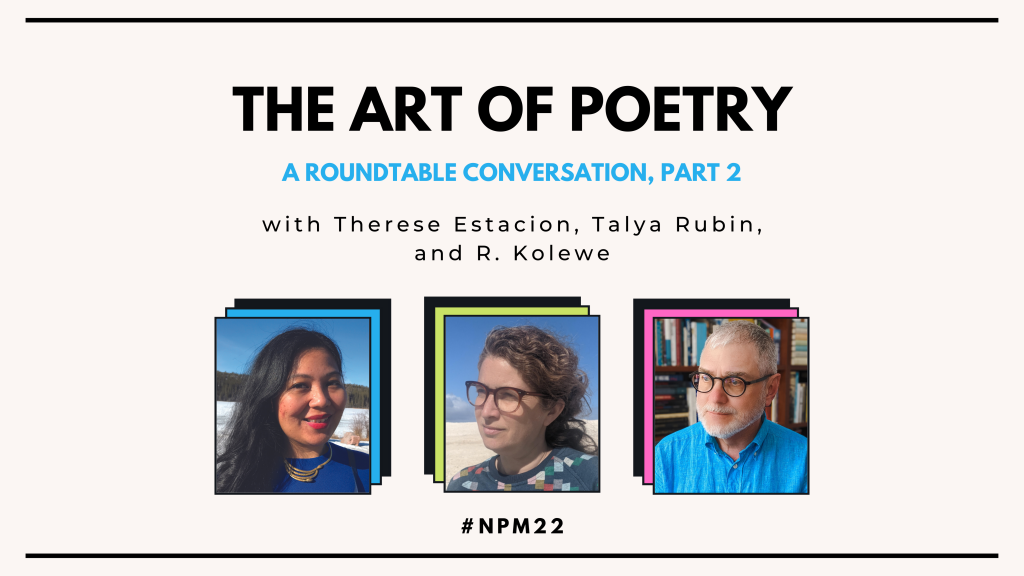

The Art of Poetry Roundtable, Part Two

As we continue to celebrate National Poetry Month, we return with Part Two of the Art of Poetry Roundtable! This time, Therese Estacion (author of Phantompains), Talya Rubin (author of Iceland Is Melting and So Are You), and R. Kolewe (author of The Absence of Zero and Afterletters) are sharing the scoop on their creative practices and some of the influences that animate their work. Without further ado:

B*H: How did you find your way to poetry?

Therese Estacion: I took some poetry classes after work to pass the time and really enjoyed the flexibility the genre gave me. I also started to enjoy reading poetry and the intensity it made me feel.

Talya Rubin: I think it was being surrounded by an appreciation for language and the origins of words growing up. My mum is an actor and a translator and between playing definition games as a child with obscure words from the Oxford English Dictionary, and cueing my mum on Shakespeare, I think I was just saturated with language. That, and growing up Jewish and Anglophone as a bit of an outsider in Quebec probably helped. I think it’s also innate, a way of seeing the world, a sensibility that you’re simply born with. An astrologer once told me I was born under a “Black Moon Lilith”. She said it was a poet’s moon. So, I guess there was just no escape!

R. Kolewe: Like most teenagers who read books, I wrote (excruciatingly bad) poems, under the influence of Rimbaud (of course) and TS Eliot, with maybe a bit of Robert Duncan and early Robert Bringhurst mixed in. I also wrote science fiction stories, heavily influenced by Samuel Delany and Ursula Le Guin, which I suspect were also awful. Thankfully none of that stuff survives. One of the things I realized, although I didn’t articulate it to myself in this way, was that I simply couldn’t think in terms of plot: what interested me in the stories was the background, the history and texture of the places where the stories were set, and the way language could bend and warp to invoke that. It didn’t matter what happened: the language mattered. And what was poetry but purified language? So I continued writing awful poems for a few decades until they started to be less awful.

B*H: Desk, café, library, or outdoors?

Therese Estacion: On the couch, prosthesis off.

Talya Rubin: I usually start out at my own desk, surrounded by notebooks and research. But after some time, I need to mix it up and I often enjoy writing in noisy places like cafés. Something about drowning out background noise can lead to an interesting kind of inner focus, and I seem to work well with that tension, depending on where I am at in the process of writing a poem. I also love combining writing poetry with a walking practice. Going for long walks in nature or in urban settings and bringing a notebook with me can spur new ways into work.

R. Kolewe: I usually write at my desk, or at a table on my deck, which I suppose means outdoors. I rewrite in those same places, and in cafes, rarely. The only libraries I’ve enjoyed writing in are the BAnQ in Montréal, where much of what became Inspecting Nostalgia was revised, and the New York Public Library’s main branch, where a large part of the Wild Fox section of The Absence of Zero was written in early March of 2020.

B*H: Pen, pencil, or word processor?

Therese Estacion: Processor.

Talya Rubin: I’m definitely a write by hand in notebooks with a pen kind of writer. I love the visceral feeling of ink on paper.

R. Kolewe: Pen for first drafts, word processor (actually a plaintext fullscreen text editor, never Microsoft Word, I despise Word and only use it when forced to) for rewrites, though I also print drafts and scribble on them. With a pen.

B*H: Do you start with a single poem or an idea for a book?

Therese Estacion: Single poem, but I pay attention to any connecting themes and see if I can start creating a collection based on what’s coming up for me.

Talya Rubin: Usually, it has been a single poem and then another, and another, and the poems will show me the way, pointing towards a more unified idea for a book through what emerges. I rarely start with a pre-conceived thematic idea for a collection. I let the poems tell me where they want to go and what they are trying to say on a larger level.

R. Kolewe: Hmmm, neither, or maybe both. In the case of both Afterletters and The Absence of Zero, it took a while to realize that what I was writing was a book and what its shape had to be. With Inspecting Nostalgia I looked at my notebooks and realized I had a whole pile of poems that were vaguely related to each other, but could make a book. A Net of Momentary Sapphire, which comes out next year, is kind of a bit of both.

B*H: What do you do if you hit a wall or feel discouraged during the writing process?

Therese Estacion: I go for a drive or I read a book of poetry.

Talya Rubin: I often need to take a break and take a step back from the work if I hit a wall. I find it tends to mean I am forcing something or trying too hard to take the work in a particular direction. For me, when I am blocked, it is often from not listening to the deeper voices at work and if that happens, I need to get out of my own way and remember the source of the work and remind myself that I am not entirely responsible for writing these poems. Sometimes you just need fresh air and a walk and to do something entirely different to gain perspective.

R. Kolewe: This happens pretty much every day, or certainly every week. I have a regular meditation practice, which is a constant reminder of the transience of thoughts and feelings: that’s very useful. Just getting out of the house helps with that hitting the wall feeling, though after a couple of years of pandemic isolation “just getting out of the house” has acquired its own challenges. And discouragement? Sometimes I ask a friend to read something I’ve been working on, and that interaction is energizing and uplifting, even if they aren’t particularly enamoured of what I’ve shown them. Or I’ll read something mostly theoretical but not poetry-theoretical, like John Cage’s essays or Thomas Aquinas on different kinds of eternity or papers on arXiv about the problems with the cold dark matter hypotheses in cosmology or something, and I’ll get excited about the parallels between this stuff and what I’m writing. But sometimes discouragement isn’t so easy to get past. Then I just wait.

B*H: How do you land on a title for a poem? Is this act of naming important to you?

Therese Estacion: I often name a piece of work once I’ve completed it. I also like the idea of leaving things untitled as well.

Talya Rubin: I find titles so important. They are anchors that pin the poem to a universe, or a philosophical world. Without a good title a poem can float away and not really be known to itself or the reader. Titles often come first for me. Sometimes I will list a whole series of titles when I am writing a collection and then write my way into the poems as I go. Other times, a poem will emerge, and the title will be embedded inside it.

R. Kolewe: Yes, names are supremely important! But all my books, except for Inspecting Nostalgia, have started out with absolutely awful titles which I’ve mostly forgotten now. (I could check but I don’t want to.) And I’ve pretty much given up on titles for individual poems, since I’m now mostly writing sequences. When I did title individual poems, the title was often either a variation on a line in the poem, or a quotation from something else, more an epigraph than a title. The titles of the books are more generally descriptive, not citational.

B*H: What’s the last book of poetry you read that moved you?

Therese Estacion: Blert by Jordan Scott and Where Things Touch: A Meditation on Beauty by Bahar Orang were both profoundly moving for me.

Talya Rubin: I’ve just finished reading a new collection of poetry called Clean by the Western Australian poet Scott Patrick-Mitchell. I found the first 70 pages that directly address the author’s struggle with addiction particularly moving. The poems are very alive, the language cuts right through you. There is an ache to them. They’re just beautiful.

R. Kolewe: I can never pick just one, so two new and one old. Liz Howard’s Letters in a Bruised Cosmos and Dale Martin Smith’s Flying Red Horse are both beautiful and moving, in very different ways. I keep going back to them. I’ve also recently been going back to William Blake’s Jerusalem, and its weird incredible wonder and energy, reading it aloud. The difference between Blake on the page and Blake aloud is astounding.

B*H: What can poetry do that fiction and nonfiction cannot?

Therese Estacion: Maybe provide catharsis with a single word.

Talya Rubin: I think it can burrow inside of a person, it can whisper in your ear, it can rearrange your atoms, it can make the light in a room look different, it can make you re-see the world.

R. Kolewe: The thing that characterizes fiction is that it’s largely about events in time, call it diachronic, call it story. The thing that characterizes nonfiction is that it’s largely discursive or expository. Poetry can do those things too: there are narrative poems aplenty (fiction with a fancy prose style?) and the documentary poem is a mainstay of the Canadian long poem tradition. I don’t think either of those kinds of poetry generally do anything that prose fiction or nonfiction can’t do. Poetry that isn’t narrative or documentary, I’d say lyric but I don’t want to, which is the sort of thing I think I write, can manage a kind of synchronic, all-at-once view, that isn’t available if your concern is solely this-after-that event (fiction, narrative) or the detail of this-or-that event or thing or idea (nonfiction, documentary).

B*H: Is there a poem you have written that has remained particularly meaningful to you/close to your heart?

Therese Estacion: My “Eunuched Female” poems still stir up mourning whenever I read them, they also remind me of my experiences living in these liminal spaces- between being able-bodied and disabled, sick and healthy. I feel like those poems are a conversation between my real self and my exterior self. There’s a lot of potential space that exists within those poems that still make me curious about what I have yet to express.

Talya Rubin: The poem that sprang to mind is called “This Is Home” from my first collection, Leaving the Island. It’s about a puffin who was accidentally transported to Montreal on a freight ship from Newfoundland and was found wobbling down a downtown street and finally returned to a colony in eastern Canada. There was something incredibly poignant in that news story for me – that lost bird, my own hometown, that fact I am living on the other side of the world, being a displaced person, wondering where I belong, and feeling losses in the natural world deeply, this terrible displacement of wild animals by our human one. There was humour in it too, which I think we need, this acknowledgement of absurdity in the face of impossibly difficult things.

R. Kolewe: There’s one poem in each book. In Afterletters, there’s a poem called “The letters of my new solitude.” In Inspecting Nostalgia, there’s a poem called “Before.” Of course, The Absence of Zero is one long poem, so…

B*H: What advice would you give to your younger self, or yourself as a poet just starting out?

Therese Estacion: As a poet starting out, I would probably tell myself to rest more, and that grieving is a natural part of my writing. So yes, definitely more rest!

Talya Rubin: I think I would say don’t care what the world thinks of you. Don’t try and achieve anything in the outside world. Just stay with what is on the page and inside of yourself. Stay true to the intimacy of making the work for as long as you possibly can, until the world comes to meet you.

R. Kolewe: Read more! Read everything! Don’t just read what’s popular or topical or current, don’t just read what’s published here in Canada or the US. Learn as many languages as you can and read poetry and fiction in them. If you can’t read other languages, at least read translations. Poetry in French, or German, or Arabic, or Classical Chinese, is very different than what’s being written in English in North America in the early 21st century. And a poem that was written 10, 50, 200, 500, 1000 or more years ago and is still being read today is important, no matter who wrote it or where. Read it! Oh, and read stuff that isn’t poetry or fiction: science, mathematics, economics, history, philosophy, anything dense with ideas or detail.

As for writing, yes, just write. Don’t try to get it right the first time, don’t wait for inspiration, just write. If you write enough, you can throw most of it away and what’s left might be pretty ok. And once you’ve written something, read it aloud, to yourself, to other people, to your cat or turtle if need be. (My cat Charlotte runs away when I do that.) Because poetry is an oral/aural art. Sometimes something works on a page but just doesn’t work in voice. (Of course, sometimes that’s ok too.)

Therese Estacion is part of the Visayan diaspora community. She spent her childhood between Cebu and Gihulngan, two distinct islands found in the archipelago named by its colonizers as the Philippines, before she moved to Canada with her family when she was ten years old. She is an elementary school teacher and is currently studying to be a psychotherapist. Therese is also a bilateral below the knee and partial hands amputee and identifies as a disabled person/person with a disability. Therese lives in Toronto. Her poems have been published in CV2 and PANK Magazine, and shortlisted for the Marina Nemat Award. Phantompains is her first book.