Textured Sonically: In Conversation with Mark Truscott

Careful attention reveals that, even in moments that seem insignificant, our minds are constantly navigating disjunctions among registers of experience. Our intellect silently reminds our eyes that the car that appears to be moving between leaves is actually behind them and much larger. The sound of the vacuum cleaner in the next room is noise to be ignored. The phrase that arises in mind belongs to a conversation earlier in the day. Clear thinking demands that these navigations remain unconscious. But what if they’re meaningful, or productive, in themselves? What if they’re necessary to help us find a more meaningful place in the world? Branches explores these questions.

Jeff Latosik, author of Dreampad, calls Branches “a unique and assured meditative work, at once ancient and wholly contemporary, a space where Stevens, Ashbery, and Basho might mingle and discover some as-yet unnoticed path.” Robin Richardson adds, “Like Kay Ryan, Truscott has a knack for logical subversion, shifting perception seamlessly until one supposed certainty becomes another, and the foundation is not just shaken but obliterated. What we are left with is the expansiveness of pure potentiality.”

Book*hug intern Mary Ann Matias recently sat down with Mark to discuss his exciting new poetry collection.

❧

Mary Ann Matias: What inspired you to write this book?

Mark Truscott: It was what I suspect will always inspire me to write: my awareness of being apart, of gaps, especially the gap between my experience of myself and my experience of the world, and that between a line of text as a physical mark and the same line as a conveyor of sense. I explored similar terrain in my last book, but there I tended to approach the poem primarily as a vehicle of sense through embodiment. This time, I also wanted to allow myself to talk a bit more. I wanted to talk about how categories like subject and object in fact overlap, how we deliberately mark divisions between them in order to make sense of the world, and about how we can miss important aspects of experience when we take these divisions too seriously or don’t move them around from time to time. Also interesting to me was the very fact that we sometimes make sense of our situation by writing—by adding marks, with all their complexity, to the world. What a strange thing.

Practically, though, it happened like this: After Nature was published, when I began writing without knowing exactly what I wanted to do, I felt myself starting to write “Mark Truscott poems,” a kind of poem I already knew how to write and could just repeat without much mystery for me, and I wondered if I had been previously limiting myself unnecessarily. So I wanted to try something different, to open things up a bit. So I experimented and gradually, through trial and error, by reading my own poems, thinking about them, and then responding, found my way to this manuscript.

MM: What was your writing routine like while you wrote this book? What is your favourite writing spot?

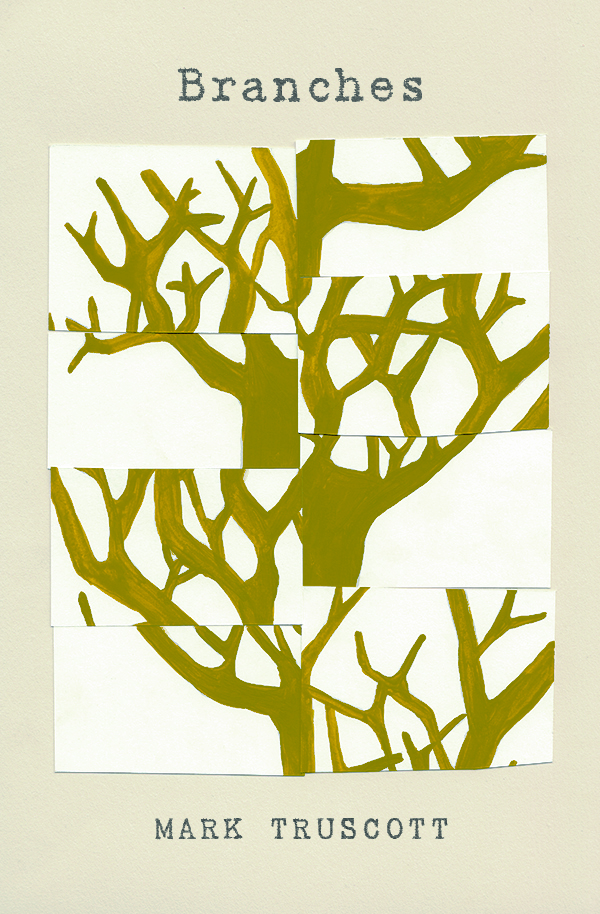

MT: I woke at 4:30 each weekday morning, made coffee, read a bit, and then wrote until 6:30 or so. I sat in the same chair and looked out the same window (I can see branches out the window, but no tree or shrub in its entirety.) I did a bit of work outside this setting, but most was there and then. I have a full-time job (as does Lisa, my wife), and we have two young children, so this arrangement was largely out of necessity. I’ve come to like it, though. Early mornings are very quiet.

MM: What motivates your writing?

MT: A big part of my motivation is dissatisfaction with the last poem. The awareness that I didn’t quite capture the impulse that gave rise to the writing, and the hope that if I change the parameters slightly, or if I come at things from a slightly different angle, I might get closer this time. I never do, of course, but then I still write another poem.

MM: What was the first thing you ever wrote?

MT: The first thing I remember writing that I thought of as a poem was about being shut out of a house that I felt I belonged in. In some ways, almost every poem I’ve written has been a version of this one. I don’t want to say that this is somehow my ur poem. Maybe my current ones are, and I’m writing out of sequence. Whatever the case, the orientation of the speaker of the poem toward the thing that’s being talked about is generally along these lines.

MM: What are you currently working on? Are there certain influences or lessons you’ll be taking from this project into the next?

MT: I’ve written five poems not entirely dissimilar from the ones toward the end of Branches. I believe they’re more textured sonically, and I think the scenes they throw light on are slightly larger. I’ll have to see where they take me.

❧

Order your copy of Branches here.

Credit: Lisa Heggum

Mark Truscott is the author of two previous books of poetry: Said Like Reeds or Things(2004) and Nature (2010), which was shortlisted for the ReLit Award for Poetry. Poems from Branches have appeared in Event, The Walrus and on the Cultural Society website (culturalsociety.org). Truscott was born in Bloomington, Indiana, and grew up in Burlington, ON. He lives in Toronto.