Stranger than Fiction: In Conversation with Jacob Wren

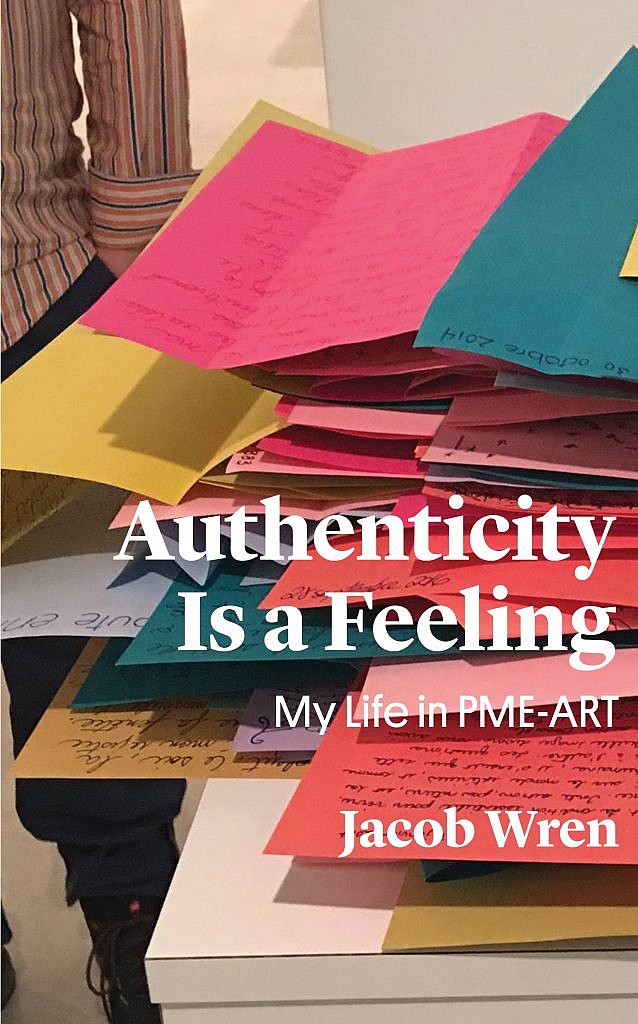

Jacob Wren’s latest book, Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART, is a compelling hybrid of history, memoir, and performance theory. It tells the story of the interdisciplinary performance group PME-ART and their ongoing endeavour to make a new kind of highly collaborative theatre dedicated to the fragile but essential act of “being yourself in a performance situation.”

Barbara Browning, author of The Gift, writes that with this book Jacob “recounts his utopian efforts at non-hierarchical collaboration over the last twenty years – not only with the members of his oddball, charming performance collective, PME-ART, but also with his spectators and readers.”

Book*hug intern Mary Ann Matias recently sat down with Jacob to discuss the writing process behind Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART, favourite books, what’s up next, and more.

❧

Mary Ann Matias: Tell us a little bit about your book and how it came to be.

Jacob Wren: Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART came out of a series of conversations in which we were trying to decide what things our collaborative, interdisciplinary performance group PME-ART might consider doing to celebrate our twentieth anniversary. Somewhere, in one of these conversations, I no longer quite remember which one, I must have jokingly said that maybe I could write “a novel about PME-ART.” And eventually that joke became the thing. Perhaps, at some point several years ago, I was actually thinking the book might be even more like a novel but, time and time again, as I was writing, the truth seemed to be stranger than fiction, what had actually happened felt to me far more interesting than anything I could think to make up, and therefore I started understanding the word “novel” in some other sense, more like a non-fiction novel, using different literary and rhetorical strategies over the course of the book to tell the all-too-true story.

And then I also found myself, at times, as I was working on it, calling it “a page-turner about PME-ART,” which I now think has a lot to do with what a “novel” actually is for me, in the sense that a novel is any book I really enjoy reading, a book that I can’t stop or don’t want to stop reading, a book that I enjoy reading even a bit too much. Somewhat later, we decided we would send the manuscript to everyone we had worked with over the past twenty years, they could comment on it freely, and I would incorporate their comments into the final version. This particular act shines a bright light onto one of the central themes of Authenticity is a Feeling, that it is a book about artists working together in a highly collaborative manner, but I am also writing about these collaborations (mostly, but not entirely) alone.

MM: What are some of your favourite books or genres? Did any of them influence this new book?

JW: I think this book has been very much influenced by books like I Love Dick by Chris Kraus, The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson, The Gift by Barbara Browning, etc. It is probably nothing like those books but I definitely had them in mind while I was writing. Those three books, along with so many others, use their first person, autobiographical narrators to speak directly about their lives and art – through the absolutely essential lens of feminism and often queerness – while I am a cis male writing about making collaborative performances over the course of the last twenty years. I’m sure my book doesn’t have the same political and personal urgency of those books, but hopefully it has some sort of urgency nonetheless.

At the beginning, I must have been thinking about how performance is usually written about, so often in a dry, academic or theoretical manner, and was wondering how to write a kind of performance theory that was equally influenced by the auto-fiction tradition, a performance theory that was therefore also achingly personal, conflicted and immediate. And now I find myself wondering: why exactly did I want to do this? Did it have something to do with honesty? With authenticity? With not believing there was any objective way to approach these questions, to tell this history, and therefore never wanting anything to feel or seem too fixed?

It definitely had something to do with bringing things together that, in my mind at least, might not fit together so naturally. The awkwardness of the combination. And I also wanted to show (and tell) what we do, and why we do it, in a way that absolutely didn’t hide all the questions, uncertainties, confusions and flaws of our practice, that was vulnerable in some of the same ways I hope the performances themselves are vulnerable in front of an audience.

MM: If there was one thing readers should know about your book, what would it be?

JW: I don’t know if people should know this, but I sort of want people to know how unsure I am about this book. I feel nervous about it in a completely different way than I’ve felt nervous about any of my other books. I have so many questions about it for which I don’t yet really have answers. About the ethics of writing about real people and the real things that have happened to us, real people who have no specific forum in which to further respond (beyond their comments already included in the book.) About setting down my reflections on performance – which I’ve always loved because it was live, ever-changing, never fixed the same way a book is fixed – and how the writing of these reflections might potentially undermine this lived, ephemeral essence of our work. (But, then again, I also feel this might be a too romantic way of thinking about performance. Something more down-to-earth might be more useful.) Concerns about how writing (my very personal, subjective) version of the history of PME-ART will change PME-ART, will change how we think of our past and what we choose to do in the future. Even though I’ve spent the past four years writing this book, I have to admit I was never completely sure it was a good idea, and I’m still not sure it is, but I hope this very uncertainty is also the strength of the book, what makes it so unusual and vulnerable in comparison to my other books.

MM: What are you currently working on?

JW: This fall PME-ART will make a new performance, in some ways connected to the book (as the title suggests), entitled A User’s Guide to Authenticity is a Feeling. It will premier in October at Inkonst in Malmö, Sweden. And then go on to be performed in Düsseldorf and Reykjavík. In Düsseldorf, at the FFT (Forum Freies Theatre) they will also be organizing a conference around PME-ART, Authenticity is a Feeling and more general questions regarding the state of collaborative performance today. I’m very curious as to what people will say and what I might learn there.

MM: Can you describe your writing process? What motivates you, and how do you deal with the challenges of this process?

JW: Since apparently I do have some sort of double life – half of my life spent making collaborative performances, the other half spent writing books – one question I often get asked is how are these two artistic lives similar and how do they differ. There are a couple of different ways of answering this question, and how I think about it has changed a great deal over the years.

I think at first I started writing novels, trying to re-invent myself as a novelist, as a way of trying to escape, or take a break, from my performance-making life. All of our performance work is based on the paradox and vulnerability of “being yourself in a performance situation,” and therefore in my novels you can almost see me actively fleeing from that limitation, doing all the things I would never allow myself to do in a live situation. Most of the things that happen in my books could physically happen in reality but the books are also, more or less clearly, not reality, more in the world of theory, thinking, dreams, parable and fable. So, in this sense, my books were a way of escaping from the overwhelming reality (or feeling of authenticity) that was at the heart of the performance work.

But then, over the years, I started to think of it all in a different way. Both my books and the performances have a fairly intensive quality of structured improvisation. At the very beginning of writing a new book I have some idea what will happen, but most of it is left open, and as I write I try to constantly surprise myself, keep myself on my toes, with the idea that if I’m engaged and surprised the reader will be as well. Most of our performances also have a clear structure in which much is left open, and as we’re performing there are always things, small and large, that have never happened before, that are happening in the moment, and this quality of moving freely through a pre-determined structure, and surprising each other, and surprising ourselves, is always my favourite aspect of the particular ways we engage with the act of live performance.

In some ways, if I were to now speak more specifically about Authenticity is a Feeling, it represents the two separate parts of my “double life” coming together, I often find myself thinking of it as a kind of car crash between the two separate parts of my artistic life, which for the most part, in the past, I’ve kept as distinct as possible. It’s a coming together of things that have never really come together before, and this is intriguing, though I’m still more fully trying to understand why and how and what it means and what the future repercussions might be.

MM: If you had to describe your book in one word, what would it be and why?

JW: Perhaps I would go with the word “liveness.” So much of what we’ve done in performance over the past twenty years must have to do with the desire to make something live, something alive, something that feels like we’re really doing it and that something is at stake in our desire for its immediacy. The opposite of phoning it in. Being there live and in the moment. I have so many questions about what this feeling is and why it might be important. Often I wonder if it’s important at all. But, nonetheless, I believe “liveness” is one of the main things the book is about and also one of the main questions in the actual writing itself. Can writing contain or embody liveness? Can a book?

MM: Have you ever had to let a writing project go? How do you know when it just isn’t working, and how do you move forward?

JW: There are so many books that I’ve started writing and then never finished. I think I’ve even lost count. Somehow, I find it very easy to work on something for six months, or even a year, and then simply walk away when I finally decide it’s not working and not going to work. And yet, in another sense, all of these failed attempts come back into the next book or the one after that. Ideas that I thought I had dropped forever suddenly re-emerge in a completely different form, most often when I least expect it.

❧

Order your copy of Authenticity is a Feeling: My Life in PME-ART here.

Credit: Jacob Wren

Jacob Wren makes literature, performances and exhibitions. His books include: Unrehearsed Beauty, Families Are Formed Through Copulation, Revenge Fantasies of the Politically Dispossessed, and Polyamorous Love Song (a finalist for the 2013 Fence Modern Prize in Prose and the 2016 ReLit Award for Fiction, and was named one of The Globe and Mail’s 100 Best Books of 2014). His most recent novel Rich and Poor, was a finalist for the 2016 Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction. As Co-Artistic Director of Montreal-based interdisciplinary group PME-ART he has co-created the performances En français comme en anglais, it’s easy to criticize, Individualism Was a Mistake, The DJ Who Gave Too Much Information and Every Song I’ve Ever Written. He travels internationally with alarming frequency and frequently writes about contemporary art. Connect with him on his blog (www.radicalcut.blogspot.com) or on Twitter @everySongIveEve.