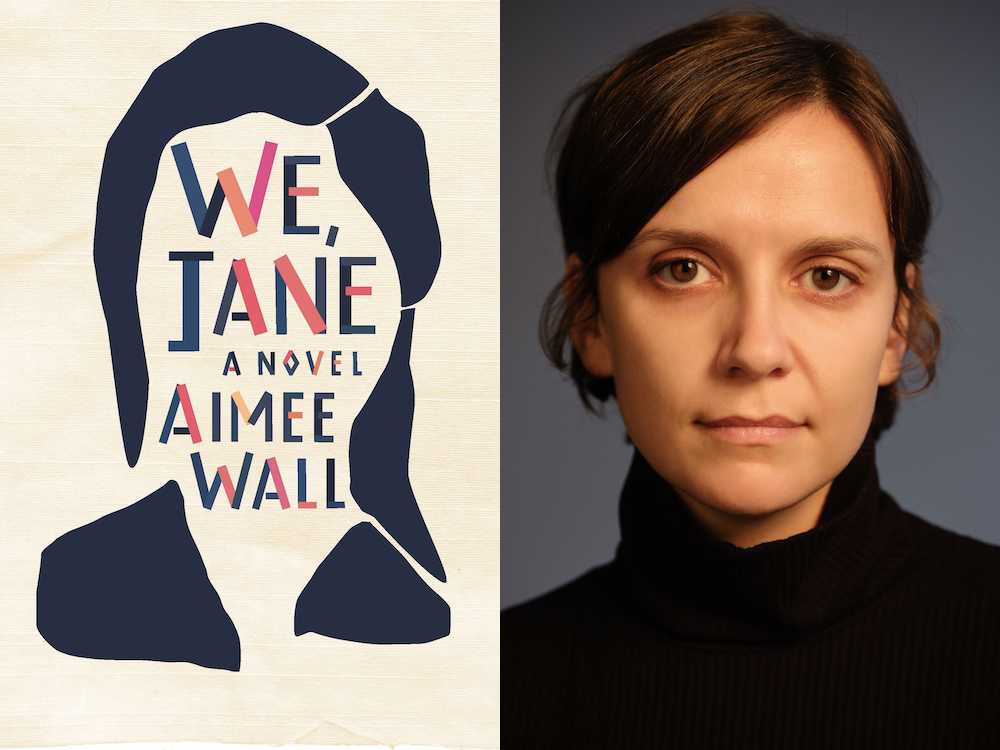

Spring Fiction Preview: We, Jane by Aimee Wall

Friends of Book*hug, meet Spring 2021. Earlier this year, we unveiled the forthcoming titles in our Spring 2021 season, but now it’s time to get to know the authors and their books a bit better. For the next couple of months, we’ll be highlighting individual spring titles, and sharing some thoughts from the authors and some exclusive excerpts on the blog.

Today, we’re excited to preview Aimee Wall’s We, Jane, a remarkable debut about intergenerational female friendships and resistance found in the unlikeliest of places. Wall is a celebrated translator of cutting-edge fiction—including Vickie Gendreau’s Testament and Drama Queens and Jean-Philippe Baril Guérard’s Sports and Pastimes—and We, Jane, her fiction debut, is equally prescient and compelling. The novel follows the Montréal-based, Newfoundland-born Marthe, who begins an intense friendship with an older woman—also from Newfoundland—who tells her a story about a duty to fulfill back home. We, Jane explores the precarity of rural existence and the essential nature of abortion, and probes the importance of care work by women for women. It beautifully captures the inevitable heartache of understanding home.

As promised, we’ve selected an excerpt from We, Jane, which you can read and enjoy below. The book is forthcoming from Book*hug Press on April 27th, 2021, and is available now for pre-order, either in our online shop or from your local independent bookstore. Be sure to stay tuned for more exclusive, never-before-seen sneak peeks of our forthcoming titles, and don’t forget: until March 12th, 2021 at 11:59 p.m. EST, we’re offering 25% off all Book*hug titles by women, including We, Jane. Use code IWD21 at checkout.

Jane had told Marthe all her other ideas were no good. Too didactic. Marthe had been thinking herself an artist and this so much raw material. Jane told her she was never going to make anything good if she was trying to convince people of something. Marthe thought of all the ideas she’d been happily convinced of. How upfront were those agendas? She of course misremembered, she wasn’t really sure.

But what if it’s funny, Marthe asked. Then maybe, Jane said. But is that really your strong suit?

It was only when Marthe decided to write the Great Canadian Abortion Novel that she’d started having bad dreams. She had been imagining herself diligently researching, spending long days in the library surrounded by stacks of books. She had been imagining the novel as a great moment, a breakthrough, even as she wasn’t entirely sure of the revolutionary nature of anything she’d have to say on the matter. She was focused on the saying part. But she got bogged down in the research phase.

Then she thought about comedy. She could do stand-up! This was the greatest untapped source of jokes she’d ever encountered. Why would nobody joke about it with her. They all shifted uncomfortably as they made laughing sounds. Marthe just wanted to joke about it. Take the piss out of the whole thing. She did, she really did, she had examined her own urges the way a woman who’s been to a handful of therapy sessions would, just to make sure, but it really did all mostly strike her as absurd and strange. And funny! She probably couldn’t get away with actual stand-up but maybe it could be, like, performance art stand-up, Marthe thought. Funny in an awkward, painful way.

Google search: art projects about abortion

Google search: aborted pregnancy art

Google search: abortion art

Don’t look at the image results.

A woman named Angie who live-tweeted her abortion.

A woman named Emily who filmed hers.

A YouTube clip in which Tracey Emin sucks and gnaws on lychee berries and says about learning more about creativity from her first abortion than anything at art school.

A woman named Aliza who told Yale University that she had potentially deliberately miscarried in a serial fashion. The shit had hit the fan. How dare she bleed out of her own womb, her own pussy, what may or may not have been cells that could have become a baby. The piece was the story of the piece. Her senior project. Are you sorry for what you did to Yale? they asked.

And then, Jane.

She wasn’t Jane yet but Marthe’s backward gaze was Jane-tinted now. Jane the sharpest eye in the room. Jane a thatch of eyebrows meeting in the middle. She was itching and anxious till Jane.

Jane catching her eye. Jane really seeing. Jane inviting her along. Jane’s long vowels sounding like home.

A sudden wave of vague, familiar longing. Knife-sharp and then duller, aching. This is how they’d do it then. This is how they’d do something, this is how they’d go home.

Newfoundland-native Aimee Wall is a writer and translator. Her essays, short fiction, and criticism have appeared in numerous publications, including Maisonneuve, Matrix Magazine, the Montreal Review of Books, and Lemon Hound. Wall’s translations include Vickie Gendreau’s novels, Testament (2016) and Drama Queens (2019), and Sports and Pastimes by Jean-Philippe Baril Guérard (2017). She lives in Montreal. We, Jane is her first novel.