Recommended Reading: Six Books to Help You Wrap Your Mind Around the Sixth Extinction

Today, we’re delighted to share a reading list curated and annotated by Kate Sutherland, author of The Bones Are There (published on October 13th) and How to Draw a Rhinoceros. We asked Sutherland to write about some of the books, ideas, and images that influenced her most recent poetry collection, which draws identifiable connections between various animal extinctions and human legacies of imperialism, colonialism, capitalism, and misogyny. The result—this reading list—is a powerful addition to the book’s call for environmental and social justice.

❧

Six Books to Help You Wrap Your Mind Around the Sixth Extinction

by Kate Sutherland

We’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction. Mass extinctions have been defined by scientists as events in which “substantial biodiversity losses” occur globally in “a geologically insignificant amount of time.” In one of the previous five, dinosaurs disappeared. In another, dubbed “the great dying,” nearly all life on earth was wiped out. Species extinction is now understood to be a natural process but ordinarily, for mammals, it occurs at a rate of about one species every 700 years (the “background extinction rate”), for amphibians, about one species every thousand years. One doesn’t need to spend much time reading the news to realize that the extinction rate in recent centuries has accelerated dramatically beyond those numbers. And the twist in the sixth mass extinction is that it’s the first time we can point to one species as the cause of the loss of the others, that cause being us, the human animal.

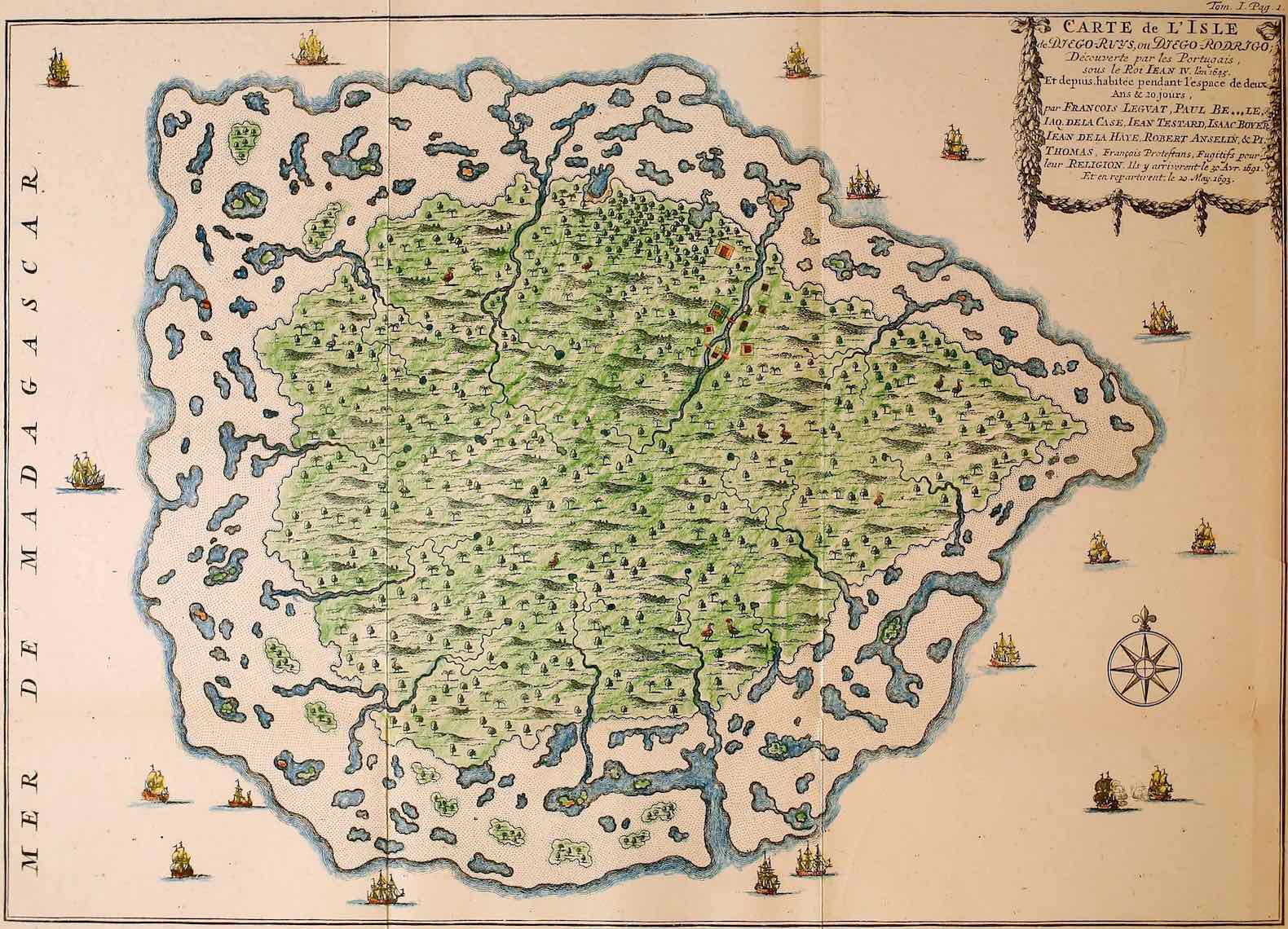

In The Bones Are There, I focus on the extinction stories of specific species: Steller’s Sea Cow, the Rodrigues Solitaire, the Thylacine, the Gastric Brooding Frog. But I felt the need to understand the broader context within which these stories unfolded and to that end did a lot of background reading. The following are some of the books that I found particularly illuminating.

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (Picador, 2014).

This is the first book on the subject of extinction that I read and it was a perfect place to start. Science journalist Kolbert is an unparalleled explainer and a vivid storyteller as well. Each chapter tracks the disappearance of a different species that she considers emblematic, some long gone, others recently departed, and others still with us but critically endangered. She thereby ranges widely through time and space, but in weaving these specific stories together provides a broad overview of the sixth extinction. In her prologue, she acknowledges that extinction, particularly mass extinction, is a morbid topic, but also a fascinating one, and indicates her wish to convey “the excitement of what’s being learned as well as the horror of it.” She succeeds amply on both counts.

Mark V. Barrow, Jr., Nature’s Ghosts: Confronting Extinction From the Age of Jefferson to the Age of Ecology (The University of Chicago Press, 2009).

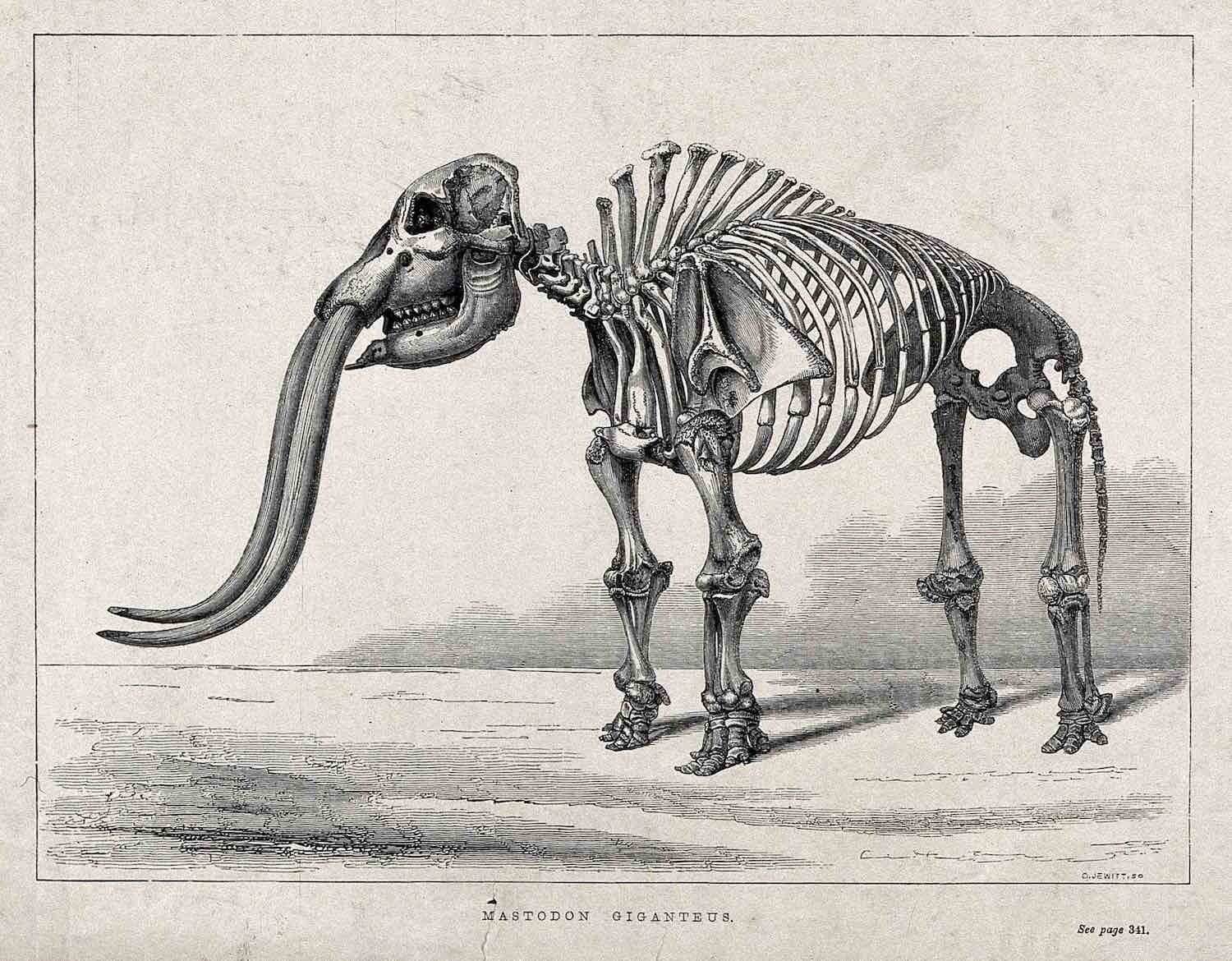

Barrow’s U.S.-focused book is a history of science and of scientists that tracks the understanding of and response to the phenomenon of species extinction from the first glimmerings of the 18th century through to the passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. He begins with Thomas Jefferson, an amateur naturalist as well as a professional politician, who, like most at the time, resisted the idea of extinction believing that God would not create an animal only to let it disappear. So convinced was he that the fossils he keenly collected must belong to animals still existing that when Lewis and Clark embarked on their 1802 expedition to map the western half of the country, Jefferson instructed them to keep an eye out for living mastodons and mammoths. But within a few decades, thanks to the work of Georges Cuvier (founder of paleontology) and others, scientific thinking shifted and the reality of extinction gained ever wider acknowledgment. Barrow tracks this shift and all that followed from it, focusing on naturalists and the ways in which their work of collecting, describing, and classifying wildlife was central to identifying the problem and its magnitude, and how it served to galvanize conservation efforts.

David Quammen, The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions (Scribner, 1996).

The field of Island Biogeography has become central to the understanding of evolution and extinction. To go straight to the source, one must read The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson. But if, like me, you find a lot of equations and graphs more confusing than elucidating, I recommend that you choose Quammen as your guide. He transforms the science into a sweeping narrative, making central characters of MacArthur and Wilson as well as their predecessor and Darwin-rival Alfred Russel Wallace, which continues riveting through 700 pages. I carried this tome around with me like a talisman as I wrote The Bones Are There, and midway through reading it, the section of my book that I had originally conceived as a poem-essay on the history of extinction fragmented into small islands of text.

Tim Flannery, A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World’s Extinct Animals (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001).

In this book, Flannery catalogues 104 animal species lost to the world since 1500, outlining what is known about each, their habitat, and the likely causes of their extinction (and in beginning in the “age of exploration,” highlighting the role of European colonial expansion in these losses). Each of Flannery’s word portraits is accompanied by a reproduction of a painting by Peter Schouten, originally painted life-size after much research. In the introduction, Flannery writes of their process: “Because it was essential for Peter to create images that would be as accurate as possible, we both made numerous trips to museums that held relevant specimens. There we would photograph, sketch and make notes on the faded and distorted specimens; and these records, along with written accounts and sketches drawn from life, made up the references we needed for the artwork and text.” Schouten’s paintings sometimes offer a first glimpse of an animal we might not otherwise have been able to imagine, and other times serve as a corrective to the images by which we believed we knew them. Consider, for example, the dodo, that icon of extinction that many of us think we know from ubiquitous images dating back centuries. But apparently none of those were drawn from life, or even by anyone who had ever seen a live dodo. Instead, they worked from over-stuffed taxidermied specimens that produced the familiar comical profile that does not match what contemporary scientist believe, based on its bone structure, to have been the dodo’s actual shape (see for example, the above reproduction of William’s Hodges dodo painted circa 1773). I’ve made a lot of trips to natural history museums myself, and am grateful for this compendium that effectively gives me access to the resources of many more.

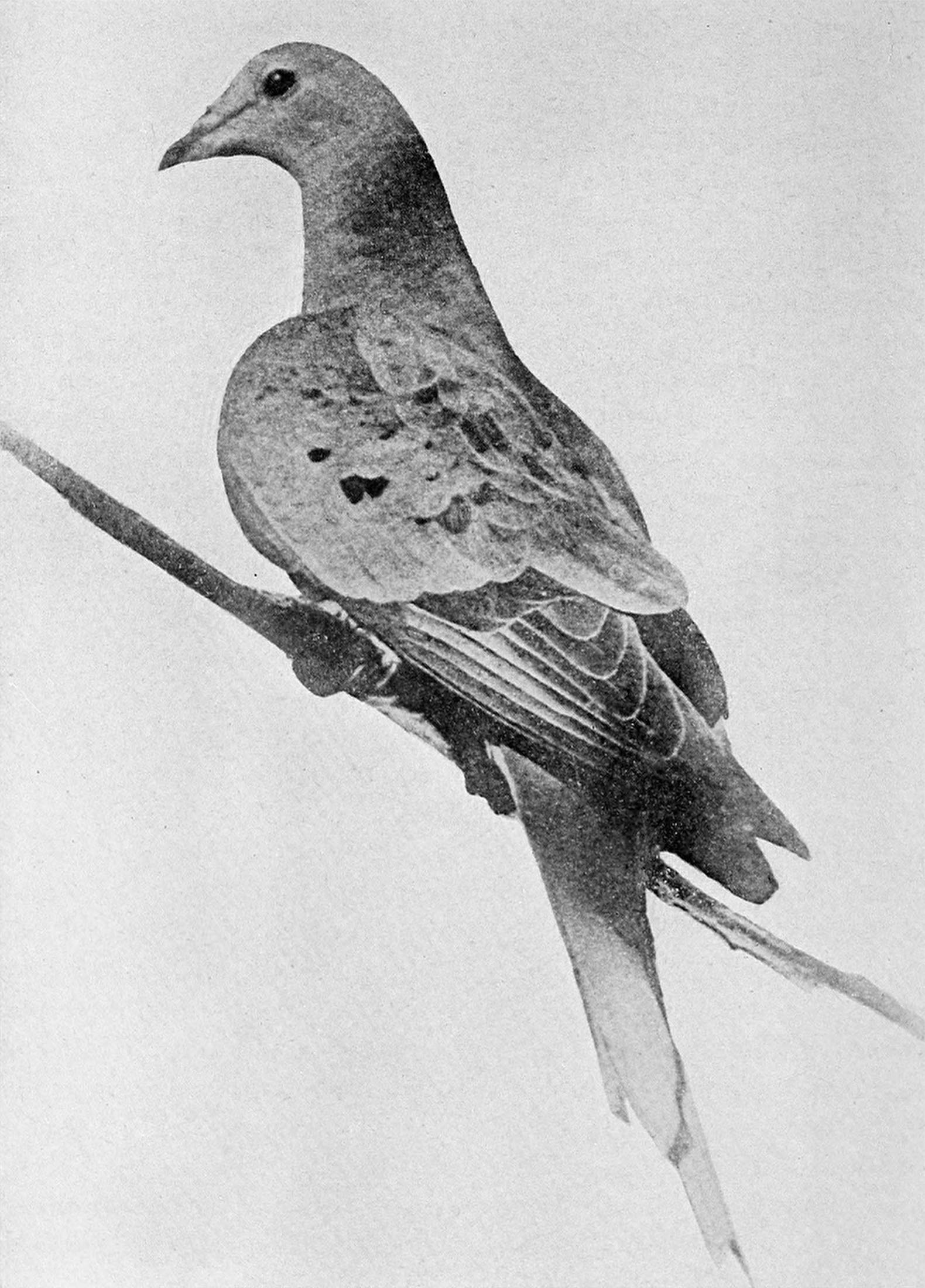

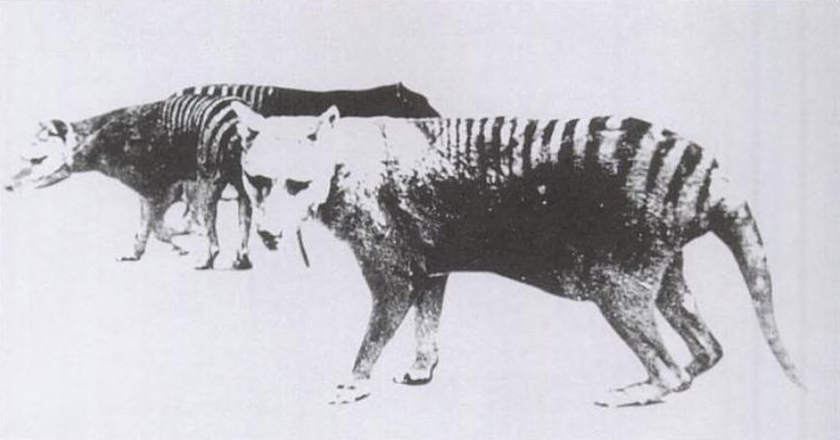

Errol Fuller, Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record (Bloomsbury, 2013).

The flap copy of this book boldly asserts, “A photograph of an animal long-gone evokes a feeling of loss more than a painting ever can.” And in 28 chapters devoted to 28 animals lost to us in “photographic time,” Fuller makes good on this claim with the reproduction of a haunting array of photographs. I find the early, ghostly, black and white photos of captive creatures in their last days, such as passenger pigeons and thylacines, to be particularly evocative.

Britt Wray, Rise of the Necrofauna: The Science, Ethics, and Risks of De-Extinction (Greystone Books, 2017).

The terms de-extinction and resurrection science have been bandied about a lot in the last decade, and what they describe is just as startling as it sounds. The quest is to return extinct species to the world or, at least, introduce replicas of them, through a variety of scientific techniques including cloning and gene editing. If you’re thinking Frankenstein and Jurassic Park, so is Wray who invokes both at different points in this exploration of de-extinction. She walks us through the science, describes various attempts at putting it into practice, past and ongoing (the woolly mammoth, the thylacine, the gastric brooding frog, the heath hen), and, more so than any other source on this I encountered, keeps ethical questions front and centre (from the introduction: “my larger focus is on the cultural, ethical, environmental, legal, social, and philosophical issues that de-extinction sets free into our world”). Consider, for example, the implications of resurrecting a species that went extinct because of habitat loss without restoring that habitat. Even apart from the limitations of the science, this is no easy solution to extinction.

I won’t say “happy reading,” as reading on the topic of extinction is never going to be happy. But such reading can be fascinating, informative, and galvanizing, and these six books make it so.

❧

Kate Sutherland was born in Scotland, immigrated to Canada as a child, and grew up in Saskatoon. She studied first at the University of Saskatchewan, then at Harvard Law School. She is the author of two collections of short stories, Summer Reading (winner, Saskatchewan Book Award for Best First Book) and All in Together Girls, and the poetry collection, How to Draw a Rhinoceros (shortlisted for a Creative Writing Book Award by the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment). Her stories and poems have appeared in various magazines and anthologies including Best Canadian Poetry and Best American Experimental Writing. She has done residencies at Hawthornden Castle in Scotland and at the Leighton Artist Studios in Banff. She lives in Toronto where she is a professor and conducts research in the fields of Tort Law, Feminist Legal Theory, and Law and Literature at Osgoode Hall Law School, York University.