Language would not exist without the body: In Conversation with Sandra Ridley

Sandra Ridley’s latest book, Silvija, is a sequence of five feverish elegies which combine narrative lyric and experimental verse styles to manifest dark themes related to love and loss: the traumas of psychological suffering (isolation and confinement), physical abuse (by parent and partner), terminal illness (brain tumour and heart attack), revelation, resolution, and healing. Pulsing with the award-winning writer’s signature blend of fervour and sangfroid, the serial poems in Silvija accrue into a book-length testament to a grief both personal and human, leaving readers with the redemptive grace that comes from poetry’s ability to wrestle chaos into meaning.

Sandra recently spoke with Wanda Praamsma, author of a thin line between, to discuss her new book.

Wanda Praamsma: Could you talk about the process of creating this poem? What was the initial seed and how did you work from there?

Sandra Ridley: Silvija ended up taking a different route than usual in that there was no tangible, directed impetus. In previous books, I began with a clear intention with plans and endpoints in mind. This book was pieced together from fragmentary, isolated long poems that had been written over five years or so, each with seemingly disparate purposes and sources. A few were written in response to art created by Michele Provost (http://www.micheleprovost.ca) and Pedro Isztin (http://isztinfoto.com/study-of-structure-and-form/).

These sporadically created long poems merged into a larger sequence in the middle of a sleepless night. That night gave me a revelation of sorts. Maybe clarity? I saw how the separate parts could work together. They spoke to each other. All sourced from the same kindred impulse or origin; there was consanguinity. The poem “In Praise of the Healer” became a tether, as it had to, by weaving between the others—or think of it as a bloodline, a life sustaining breath from first gasp to last. If there’s a central, sustaining poem in Silvija, I’d like to think that’s it.

WP: As the reader, I get to create and see images for certain things in your poem. Other things are so well hidden, no images appear. Then there is this line: we will/Never depend upon our eyes. How does ‘seeing’ and vision shape this narrative?

SR: It’s through our senses that understanding begins and ends. Can we trust this? There’s the visible, the hidden, the missing, and the absent. Each of these things has its own potency. Even the smallest of images, pure, obfuscated, or their absence, contain worlds of experience. What are we experiencing—what can we, what will we? How do we bear witness to the traumatic? We’re left with hauntings in our mind’s eye.

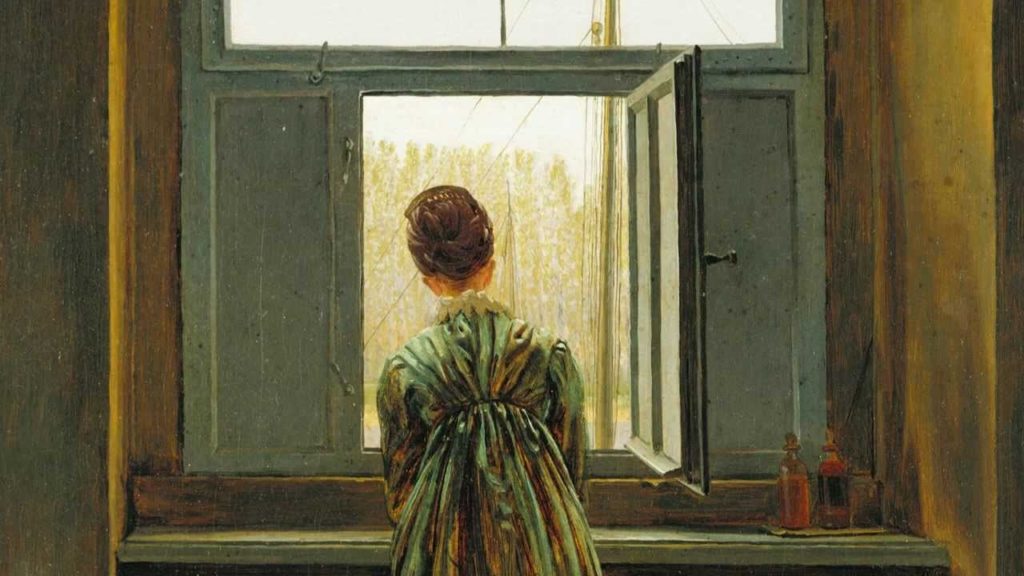

There’s a German word: Rückenfigure. It’s often associated with romantic paintings, implying the ‘back figure’. This figure turns her back to those viewers looking upon the larger image. (See above: Frau am Fenster, Caspar David Friedrich.) The Rückenfigure’s form blocks part of the view. And the viewer can’t see exactly what she herself is looking at. Because of her impeding gaze—her act of captivation as verb, not noun—layers of the work are lost to us. We, as viewers have a partial, impeded view. We have no choice but to take on her role as seer, albeit with our own impressions. As with actual lived experience, representations and interpretations become part of the view of what is seen and not seen. Our gaze is always obstructed and there are always layers to work through—and that is where a poem begins. I guess I’m curious about what is revealed and concealed in our vision.

Robert Kroetsch has a good way of putting it in his Lovely Treachery of Words, and I reference this again and again: It’s…“not the raising of the veil but, rather, the lowering of the veil, the acknowledgement of the untellability of the story, that is the generative moment, the enabling act.”

WP: Reading it as a long poem, I feel great heaviness and lightness in the body. For you, is writing poetry in the body – is it always linked?

SR: Language would not exist without the body. We wouldn’t be able to articulate it, conceptualize it, or even dream it into existence. Without the body, nourished by the breath, there would be no poems.

In a way a poem is its own transformative being; there’s an active transmutation at work. The poem assumes its own shape, its form and content, and this act is in no way passive. Writing is simultaneously transference and embodiment, with its unexpected beauty and monstrosity, with its own desire. You can never know how the writing will manifest itself.

I don’t cite “monstrosity” with any dread or implied darkness. I’m thinking of the verb ‘demonstrate’. The word comes from monore, to warn; montstrare, to show; monstrum, something marvelous, extraordinary, a prodigy, a divine portent or warning. Poetry can give form to what has been banished, to what we’re afraid to encounter and acknowledge. At its best, and best is a horrible word, poetry speaks with urgency in its own deviant and shocking voice. A poem is a beautifully monstrous form.

WP: It seems the lightness, in addition to the words, comes from space in your writing – how do you let go of words and thoughts to bring it down to the essentials?

SR: I try to be conscious of the scoring of the words on the page. White space and punctuation work as notation, like a musical score. There are so many means to embody silence, and every word, every phoneme and sound, carries its weight into that silence.

Let me stay with words. Consider: kiss. For each of us, this word entangles a spectrum of emotions arising from a complex of associated experiences and memories. This, incarnate, carries weight. Kiss. Then consider: one kiss, the kiss, lone kiss, singular kiss, last kiss, only kiss, final kiss. Even the smallest and seemingly simpler words carry enormous weight. Then add all those intended and unintended permutations and combinations, and the incantations of sound. Verberations and reverberations. I try to lighten a text by lightening the load—pare the text back and let each word, each sound, set itself into place in the mindscape and on the landscape of the page. And all that remains in the lightness of this silence becomes heightened.

Order your copy of Silvija here.

Upcoming events with Sandra Ridley:

Versefest, and NRC Showcase present Sandra Ridley, with Angèle Bassolé Ouédraogo, Mark Frutkin and Guy Jean.

Sunday, March 26 @ 1:00 pm – 3:00 pm

Knox Presbyterian Church, 120 Lisgar Street, Ottawa, ON

1pm

For more info, visit here.

Richmond Hill Public Library presents the 13th Annual Poetry Celebration, hosted by Barry Dempster, with Sandra Ridley, and Michael Fraser, Steven Heighton, Maureen Hynes, Soraya Peerbaye. Readings, Refreshments & Book Signing.

Note: Room A, 2nd Floor, Central Library. Free. Register online here.