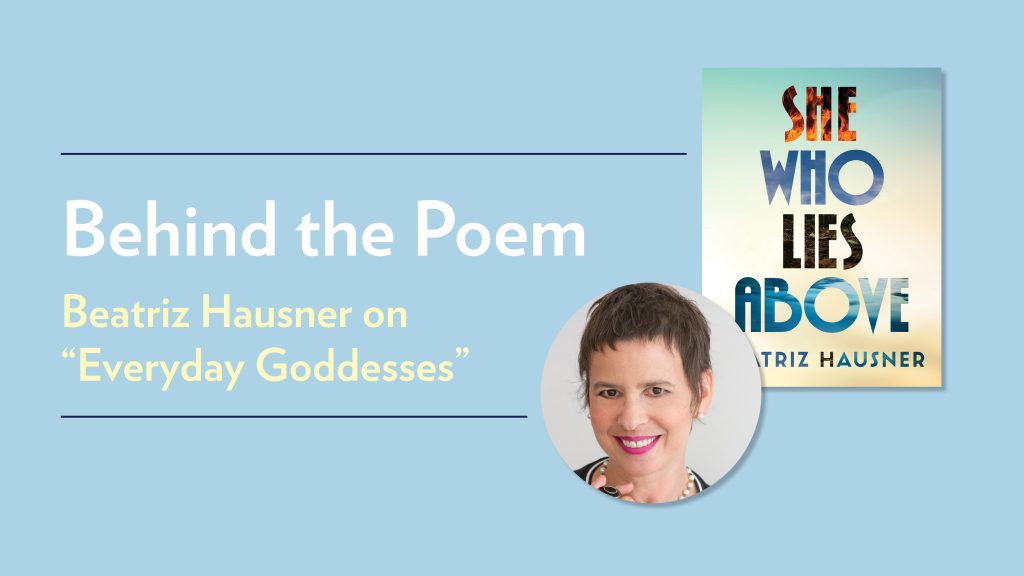

Behind the Poem with Beatriz Hausner

Today, Beatriz Hausner is taking us behind “Everyday Goddesses,” a poem from She Who Lies Above!

“Everyday Goddesses” is a distilling of a longer poem inspired by the work of surrealist artist Virginia Tentindo. I initially conceived of it as a kind of incantation in the manner of the ancient elegiac texts. It incorporates elements of alchemy, which is a running theme in She Who Lies Above.

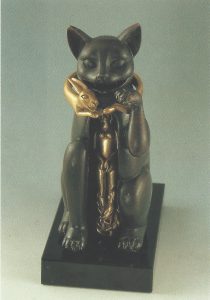

In the spring of 2019, while in Paris, I visited Virginia Tentindo’s studio. I already admired her work, so visiting her studio in the legendary Bateau Lavoir in the Montmartre neighbourhood felt like a dream come true. What I encountered there was awe inspiring: sculpture after sculpture, in stone, clay, bronze and, in the case of miniatures, gold. There were sculptures of humans that morph into animals often erotized in ways that transform bodies and objects into entirely new beings. This marked me, perhaps because Tentindo’s work feels like the expression of my poetic process made physical. They are clearly the product of a great artist, a master of the techniques. The piece that inspired “Everyday Goddesses” is titled Chat d’octobre. Here is a bronze version of the sculpture.

The sculpture evoked deities and mythic female figures that often take me back to ancient Egypt. In this poem, the goddesses I “invoke” more specifically are Bastet, represented as a cat in Egyptian art and script, and the Egyptian hare goddess Wenet.

Here is a photograph I took in Virginia’s studio of the same work, only rendered in clay. It forms part of a separate edition.

Virginia Tentindo, like many surrealists, subscribes to alchemy as a metaphorical system to express the making of surreality: the objects of the physical and psychic world (base metals), when put through the processes at work in wakefulness, dream, or revery, are conducive to the liberation of the mind and by extension, the world (gold). There is no question in my mind that Tentindo’s creations exemplify the alchemical process proper.

Here I am with Virginia Tentindo in Paris in April 2019, in the metro, on our way back from a poetry reading.

My time in Paris was spent researching much of what would become She Who Lies Above. I was able to visit the places where the medieval alchemists practiced their art, including the house that Flamel is purported to have lived and laboured in, in the 14th and 15th Century. I was taken by my surrealist friend Guy Girard to one of the bouquinistes that set up shop along the Seine. There, I happened upon an edition of Fulcanelli’s Le Mystère des cathédrales, a book that I’d been looking for. I thought it fitting to begin by reading the chapter on the Paris cathedral Notre Dame. Guided by my reading, I took the metro to Notre Dame, and seeing as the lines to enter the precinct were forbiddingly long, I determined to concentrate on the exterior first, and leave the inside for another day. Of all the images and symbols Fulcanelli focuses on, the one that I found most striking was that of Lady Alchemy, a carving situated in the front of the church, at the juncture of its very support, the bottom of the central pillar. Here is Lady Alchemy in the photographs I took that day.

In the closeup one can see that Lady Alchemy is holding a sceptre in her left hand. In her right hand she holds two books, one closed, the other one open. Held between her legs and resting on her chest is a nine-step ladder, the scala philosophorum, which in Fulcanelli’s analysis represents “the patience which the faithful must possess in the course of fulfilling the nine operations of the hermetic work.”

A few days later, as I made my way back to Notre Dame to explore the alchemical references in the interior of the building, a friend called me to say that the great cathedral had caught fire. I took the metro and got there in time to see the great building engulfed in flames, its two towers making her look like an impassive sphynx in flames. I hope to one day return, and examine the restored stone carvings inside great cathedral, but that is for another, likely very different poem.