“It is OK to Grieve”: In Conversation with Talya Rubin

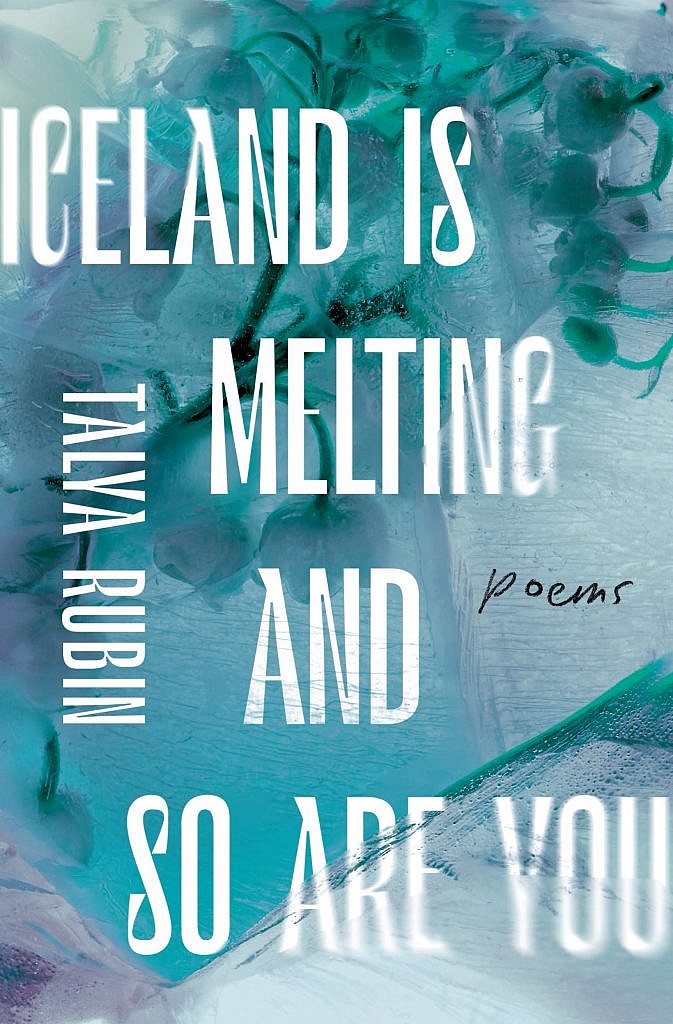

Today, we pick up our In Conversation series with the endlessly thoughtful Talya Rubin, author of the poetry collection Iceland Is Melting and So Are You. Read on to learn all about her ideas surrounding climate change and environmental poetry, and for news about the upcoming virtual launch taking place on November 10!

In the following interview Rubin speaks with feeling about her experiences of climate grief, along with her desire to face the facts and grapple with daily contradictions, the “rupture between what you know is right and what you do anyway.” We spoke about geological time, the enormity of climate losses, and the ways in which poetry might provoke climate activism. Rubin rounds off the conversation with some thoughts on natural spaces that offer inspiration and reprieve.

B*H: In Iceland Is Melting human time is laid up against geological time. Is it possible to grieve a planetary loss which exists beyond our human scale?

TR: It feels as though the human brain is in some way incapable of fathoming a lens wide enough to really take in geological time. Or if we can, it’s for a tiny glimpse and then the shutter closes again, as though it is a survival mechanism to stay with the particularities of this human life and experience. I felt very deeply that climate grief was wrapped up with this immensity of time and space, with the layers of rock and ice. As a poet, maybe it is my work to try and hold a mirror up to the impossible. I had to breathe my way into the earth. To really attempt to feel the losses on a level far beyond the human. I was reading a children’s magazine to my son at bedtime last night about the age of the dinosaurs and there was a phrase, “we don’t even know what we don’t know.” It feels like that a bit with climate grief, sometimes we don’t even know the scale of what we are losing and in what dimension.

I do also think of Aboriginal cultures and the Seventh Generation Principle based on an ancient Haudenosaunee philosophy. At least there you can find a connection to a span of human time, not just our individual experience, that connects us to the impact we are having and will have in the future and our connection to the past. Broadening that out to geological time is quite a bit more epic, and does that then connect us to our grief? If it connects us to the earth itself, hopefully it can connect us to our feelings, and to action.

B*H: Can poetry serve as a form of climate activism?

TR: I think it can, though I can’t honestly say that it was my intention to write a book of poetry about climate grief and loss as an act of activism. I wrote it much more out of a need to articulate what I was feeling and experiencing, to sit with those feelings and face them rather than have them overwhelm me on a daily basis.

I started writing the book because I literally found myself sitting on my kitchen floor weeping over the bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. I had been to that reef many years before and it was a profound sensory experience being with those corals and fish, all that colour and beauty and life. It felt like the most alive place I had ever witnessed on earth. And to think that all that life could just be drained like that, from human driven climate change, from our activity on this planet. That was just shattering. So, the book was a way of wrestling with all that I was overwhelmed by. And I thought if I am experiencing this surely many, if not most of us are on some level. And what do we do with those feelings? Just bury them? If it’s too much grief, I think we tend to shut down and get on with life—do nothing to face what we are feeling for as long as that is tenable.

Poetry has a subtle effect on the human psyche. It doesn’t hit you over the head with facts that are hard to swallow. In that way, it truly can be a form of activism. If it can go deeper inside a person, inside a reader, then maybe it can help us to confront what is really going on and do something about it.

Most of the time, when it comes to the climate, we are too paralyzed by grief to get out into the world and take action. It’s so alienating to feel like we are losing our own home. This new word, “Solastalgia,” was recently coined by the Australian philosopher, Glenn Albrecht, to describe it. It means having a feeling of homesickness in your own home, in your own environment. If we have that degree of disconnect where our own environment starts to make us feel overwhelmed and potentially alienated, we need a means of dealing with these feelings. I do believe poetry can assist with that. And the follow-on effect would hopefully be more people strengthened to go out into the world and do something about it.

B*H: Many of us cope with climate change by pushing it to the back of our minds. How did it feel to confront the climate crisis head on by exploring it in your writing?

TR: Very cathartic, actually. It felt a lot better than repressing it. Sitting with all the things that were swirling around in my mind was incredibly calming and I found that it became a kind of practice, sitting with things as they are, rather than trying to push them away. We are so busy living our lives, living over top of all the grief that is there that it felt like a gift to be able to live with it.

B*H: What did you read while writing your book?

TR: Loads of news articles on climate change, geology, cloud formations—anywhere my instincts led me. I gorged myself on news, looking for something that would spark emotion or that was odd or stood out and would inspire a poem. The permafrost melts and the discovery of ice age animals and artefacts really fascinated me. There were lots of articles about mass extinction or whales beaching or coral bleaching. Not too cheery, really. I also read about ice sheets melting and glaciers, how they are formed and what is happening to them right now. I tried to get a lot of facts and information in my head so that I would have it in there somewhere, whether I used those facts or not. It was more about having as much information as I could and then transforming that into poetry.

I also read a bunch of books:

- The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert

- A Wilder Time: Notes from a Geologist at the Edge of the Greenland Ice by William E. Glassley

- Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence by Timothy Morton

- What We Think About When We Try Not To Think About Global Warming: Toward a New Psychology of Climate Action by Stoknes, Per Espen

- Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane

- Learning to Die: Wisdom in the Age of Climate Crisis by Robert Bringhurst and Jan Zwicky

B*H: What new book, or books, are you looking forward to reading?

TR: To be honest, the book I would most like to read right now is Gardening Through the Year in Australia! I find Australian soils and seasons quite mystifying still. Canada seems so straightforward, growing seasons are clear cut and soils are very naturally rich. So, understanding the natural environment in a place I didn’t grow up in feels like a big task.

In my other life, I’m the co-artistic director of a contemporary solo theatre company called Too Close to the Sun. We work with objects, artefacts, and layered imagery to make contemporary performance. I would love to dive into a collection of essays put together by John Bell called Puppets, Masks, and Performing Objects. We’re making a new work right now about the liminal space between life and death. I’m interested in a book called Faces of the Living Dead by Martyn Jolly. It’s all about the history of spirit photography.

I’m also very curious about A Feathered River Across the Sky by Joel Greenberg. I’ve just started thinking about a new collection of poetry and I have an instinct it is going to have birds at its centre. The book is about the passenger pigeon and why it went extinct.

B*H: What role does driving and highway imagery play in the book?

TR: I think it somehow represents the dichotomies we live out, that rupture between what you know is right and what you do anyway. Objectively, we know that fossil fuels are destroying the planet in a way that is quite monstrous. They are so clearly something we need to stop using and to think of differently. But our love of travel and ease of being able to move about is at direct odds with this knowledge that it is killing us. I think it was in the book, Dark Ecology that Timothy Morton describes a human being getting in the car, turning the ignition, and driving and how that one act is not that big of a deal. It is the multiplicity of acts adding up, it is billions of people driving that make it a problem. So, we are able to justify that one action because we don’t live in the understanding of the many, of the larger picture.

I always tried to walk everywhere I went when I was a teenager, I wouldn’t even get on a bus at times I was so worried about pollution. And then I never really owned a car until last year. I ended up living in a place where you literally cannot get around without a car. It bothers me a lot. It probably highlighted this dichotomy for me, brought it home. Who can live without roads, pathways into the future, ways of navigating the world? It represents a path through and progress, roads, and highways. But they are also destroying us and the natural world.

B*H: Iceland Is Melting is filled with a longing for pause, a wish to delay disaster. How do you find moments of reprieve in a rapidly changing world?

TR: We have just moved to a house on three quarters of an acre of tangled, jungle-like garden that needs our custodianship and care. I think working in the garden trying to regenerate the land, plant native water-wise plants and a food forest is a good way to take a pause from disaster. With your hands in the earth and the bees humming in the rosemary, everything seems OK for a while. I also have a 9-year-old and I think raising a child means you necessarily have to be optimistic or at least fight for his chances to inherit a world that is better, not worse, than how you found it.

B*H: Can you share with us a natural landscape that inspires you as a writer?

TR: Banff comes to mind because a chunk of this book was written there, and that landscape is very powerful. It is almost too dramatic. I’m not used to mountains, being from Quebec where they are old and eroded. Those mountains almost hurt to look at they are so beautiful. I loved being near new mountains in Banff, it sparked a lot of my curiosity about geology and how these landscapes are formed and what we take for granted as always being there. It drove home that what we know as a place was not at all like that hundreds, or millions, or billions of years ago.

And all the wild animals, the wildness of the area. The fact that you might see a coyote chasing deer into the river to catch dinner. That there are bears in the woods and warnings about sightings. All the elk that live on campus. I found that meeting of the human and natural world so pronounced in Banff, the civilised and the wild. It’s extraordinary.

I also participated in a forest bathing session while I was there and that sort of blew me away. For many years I have been someone who has a contemplative practice of some kind and yet this was a whole new way of being with nature. It was very profound to sit with the trees in that way and to observe the natural world in silence for so long. It made me see the place quite differently and I felt so much more a part of it, both totally outside it and entirely connected to it. It was a fascinating experience. I had a much deeper sense of longing for home, for belonging on the earth, when I realised how truly disconnected we are from it, how we don’t really take time to watch movement on the ground and rustling in the leaves and a bird alighting on a branch and the particularities of place in this moment in time.

B*H: What do you want readers to take away from your book?

TR: That it is OK to feel. Feel everything, feel it deeply. That is what will heal you and allow you to step out into the world and be a force for change. That it is OK to grieve and to acknowledge what is really going on here, both inside and out.

SAVE THE DATE: Virtual Launch of Iceland is Melting and So Are You

Join us to celebrate the virtual launch of Iceland is Melting and So Are You with special guest Rufus Wainwright!

The event will be held via Zoom Webinar

Free to attend. All are welcome. Closed captions will be available.

November 10, 2021

8 pm EDT

More details coming soon!

_____

Talya Rubin is a Canadian poet originally from Montreal. She was awarded the RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers from the Writers’ Trust of Canada in 1998. Her poetry has been longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize and the Montreal International Poetry Prize. In 2015, she won the Battle of the Bards and was invited to read at the Toronto International Festival of Authors. Her first collection, Leaving the Island, was published in 2015. Talya holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia. She also runs a theatre company called Too Close to the Sun, and currently lives in Perth, Australia with her husband and son.