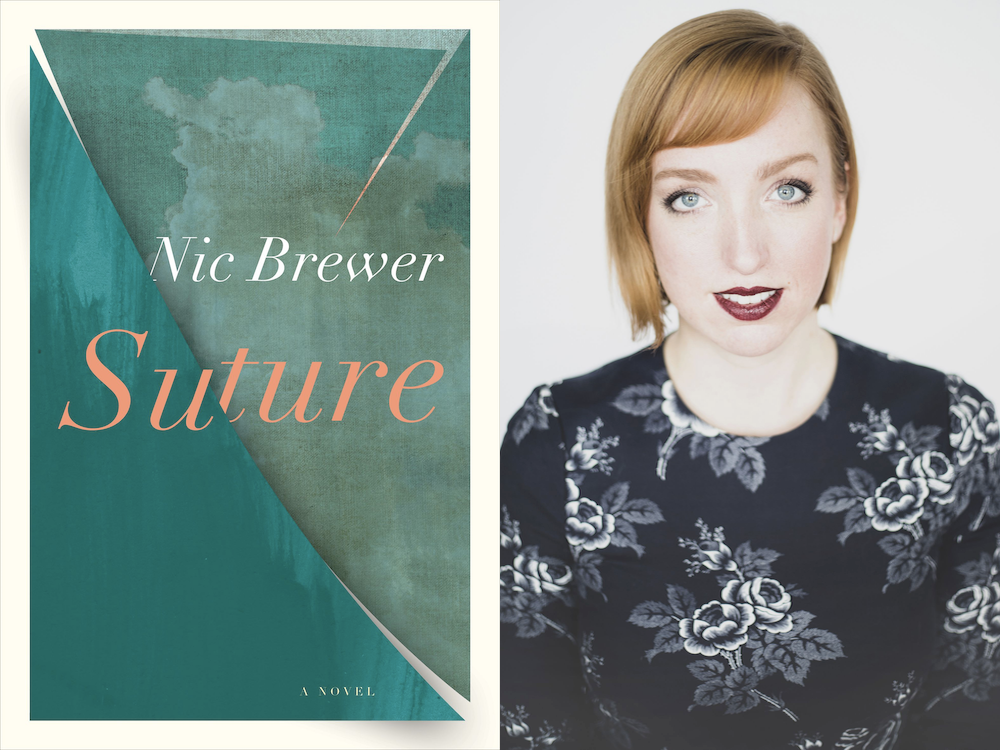

In Conversation: Nic Brewer

Continuing our In Conversation series, Nic Brewer joins us to discuss her remarkable debut novel, Suture! Suture fiercely and tenderly interweaves the stories of three artists who literally tear themselves open to make art. Each artist baffles their family, or harms their loved ones, with their necessary sacrifices. Using body horror as a means of exploring creativity, Brewer renders a new vocabulary for thinking through art, empathy, and mental illness.

The following interview reveals the deep care and consideration that went into Brewer’s near decade-long process of writing Suture. Countless books were read, characters evolved, details changed, life changed, ideas expanded, then hollowed, then softened. Brewer shares some of her thoughts on reading and writing, and what she hopes Suture will mean to her readers.

B*H: Can you describe what your book is about?

NB: You know, I’ve been copy-pasting a description of Suture here and there for a while now, but I want to come up with a new one here. I’m going to be dramatic: Suture is about making the wrong decisions. In a world where making art tears a person apart, most decisions feel like the wrong one—it feels like everything hurts, all the time. I went through a huge part of my life feeling like I’d never made a right decision, and it was lonely and painful, and I wanted to capture that feeling. Because then, Suture is also about how most decisions are not wrong, even if they aren’t right. Each character has a story with a beginning, a middle, an end, and each character’s story begins anew after its first ending. Life goes on, people change, values change, and the spectrum of feeling is beyond measure in every direction. Suture is about the horror and blessing of trying to live a meaningful life.

B*H: Can you describe the ideal reader of your book?

NB: The ideal reader of my book is ready to be at least a little bit uncomfortable for the sake of finding something new. For some readers, it might be the body horror that’s uncomfortable, and it might bring a new understanding of how painful a bad brain day can be for a person with mental illness. For some readers, it might be uncomfortable to watch characters hurt and disappoint the people they care about, and it might bring a new capacity for empathy and understanding. I think Suture will only be a comfort for the people who feel (as I do) that it’s horrific to be alive sometimes, and I hope it holds them like a blanket and I hope they feel validated in their keeping on. For others, I think it will be uncomfortable, but it is meant to be hopeful above all.

B*H: Why is body horror a useful genre for a book about art-making?

NB: I think that most horror is a really visceral way to explore things that are hard to talk about, and that body horror is no different. In the past couple of years, I became absolutely hooked on ghost stories and hauntings, because ghost stories are such an incredible way to address trauma. I hate the feeling of being scared, but I love nothing more than talking about the hard things. So while the body horror of Suture started from a lens of satirizing the absurdity of judging art, it developed much beyond that for me, into a way of expressing how much it literally hurts to be alive sometimes.

B*H: In the world of Suture, art is sometimes reproduced in factories (if the artist is popular enough). What is the role of industry/reproduction in the book?

The section you’re referencing here was inspired directly by the song “Light Leaves, Dark Sees Pt. II” by Los Campesinos, which opens: “I part the curtains of your hair / And all the light of the sun floods the room/ Poured from your sleepy stare / Two seconds each morning without fail / Before I enter the abattoir / To see my insides hanging there / But they request that I leave/ ‘Cause my sad eyes are too much to bear”

I was already crafting the novel and the world when I first heard this song (in fact, one of Suture’s earlier titles was Enter the Abattoir), and it pulled me in right away–I knew I had to write a story where someone sees their own insides, and is horrified. I suppose if you looked at this from an art point of view, there could be something in there about selling out, about sacrificing artistic integrity, but that’s not where that story came from. That story is about knowing what something means to you, and understanding that nobody else really cares about it in the same way, and how painful that is.

B*H: What about writing your book surprised you?

NB: Goodness, what didn’t surprise me? Over a decade in the making, this book took on so many different forms as I wrote it, as I changed and grew as a person and a writer. I think the biggest surprise came very near to the end of writing it, though. I had left a six-year abusive relationship, I’d realized I was gay, and I’d fallen in love with the woman who will eventually be my wife, and I was still working through some big, sweeping rounds of edits with Malcolm (a literal saint). We were struggling with bringing the parts of the story all together into a meaningful whole, without leaning into anything too kitschy. Finally, after the first Christmas with my girlfriend in our new home together, something clicked. I fleshed out one of the character’s storylines in a way I’d never been able to do before, and I realized it was because this character was meant to have a healthy, nurturing relationship – and I had no idea how to write it until that moment.

B*H: How did you know that your book was finished?

NB: I was convinced several times that my book was finished long before it ever actually was. Or, maybe that’s not quite true: I felt I’d taken my book as far as I could take it, and I needed someone to tell me if it was finished or not. I had the ending of each character’s story written long before the rest of the book, and the first time I thought it was finished was when I’d mapped out and written the stories that got us to that ending. After that, I thought it was finished when I’d filled in more of the details of each story, given each character more of a standard arc. After that, I thought it was finished when I’d managed to capture the feeling of each story in the way that I’d intended since the beginning. Let me cop out of a real answer here: is a story ever really finished? The book is done, but the story is yours to finish.

B*H: What did you read while writing your book?

NB: Oh dear, I read everything while writing this book. It took me almost a decade, after all. This is going to sound so pretentious, but one of the first books that really influenced Suture was Infinite Jest. I took a Greyhound bus from Toronto to Whitehorse and I stayed in a cabin for a week, reading Jest and writing Suture. The breadth of the book was so inspiring, and David Foster Wallace’s crisp-yet-meandering genius was the first of its kind I’d ever encountered. Kate Gompert knows how it hurts to be alive, and I was in awe of how he captured depression in her character. Some other notable books along the way were (in no particular order) A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride, Blood Fable by Oisin Curran, Endgame by Samuel Beckett, Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, All Saints by KD Miller, Air Carnation by Guadalupe Muro, Sophrosyne by Marianne Apostolides, Malarky by Anakana Schofield, All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews, What is Not Yours is Not Yours by Helen Oyeyemi, A Manual for Cleaning Women by Lucia Berlin, The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Glory by Gillian Wigmore, Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado, Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, Milkman by Anna Burns, Normal People by Sally Rooney, To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, and Heartbreaker by Claudia Dey. (To name a few.)

B*H: What new book, or books, are you looking forward to reading?

NB: Great question, let me just refer to my literal database of books I’d like to read. In all seriousness, I stepped away from Canlit these past few years to take care of my brain, so I’m referring to all of the “Most Anticipated” lists just like everyone else. I’m so excited for my fellow Book*Hug Fall Fiction books! I am rediscovering speculative fiction and discovering a love of gothic horror, so anything called “haunting” has me hooked. Some books that have specifically captured my heart are Probably Ruby by Lisa Bird-Wilson, The Pump by Sydney Warner Brooman, The Annual Migration of Clouds by Premee Mohamed, Open Your Heart by Alexie Morin, A Dream of a Woman by Casey Plett, The Quiet is Loud by Samantha Garner, Amora by Natalia Borges Polesso, and the newest books from Tilley Walden and Helen Oyeyemi. (Also, readers, please recommend me your favourite weird, haunting, queer books!!)

B*H: Towards the end of the novel, filmmaker Eva gives a beautiful lecture about how making great art is about noticing what is already there. “People—all of us—already have what we want to see, and you can show your watchers where they have hidden it.” What does Suture uncover?

Okay, this makes me sound very woe-is-me, but I hope Suture uncovers pain, and grief, and hurt. I’ve been listening to a lot of Brene Brown recently, and just today I listed to a section where she was discussing the importance of talking about what gets in the way of joy: shame and vulnerability, in her area of research. Things that hurt can hurt so badly, whether that’s the loss of a friend or partner, the loss of a job, feelings of inadequacy, low self-image, or any myriad of painful experiences, and the hurt has the power to shape us in a way that closes us off from joy. And it’s so hard to talk about, to see, hurt–because if your listener doesn’t respond with empathy and compassion, that just seems to validate every bad feeling that had piled up until that point. So in Suture’s case, every reader has what they don’t necessarily want to see, and I hope to guide them gently towards it and into a gentle, caring truth of hurt and joy being inseparable.

B*H: What do you want readers to take away from your book?

NB: I want readers to take kindness and empathy away from my book, for themselves and others. I want the readers who need Suture for its company to know that I love them, and that their worlds are a better place for having them, and that it is worth sticking around.

Nic Brewer is a writer and editor from Toronto. She writes fiction, mostly, which has appeared in Canthius, the Hart House Review, and Hypertrophic Literary, among others. She is the co-founder of Frond, an online literary journal for prose by LGBTQI2SA writers, and formerly co-managed the micropress words(on)pages. She lives in Kitchener, ON, with her partner and her dog. Suture is her first book.