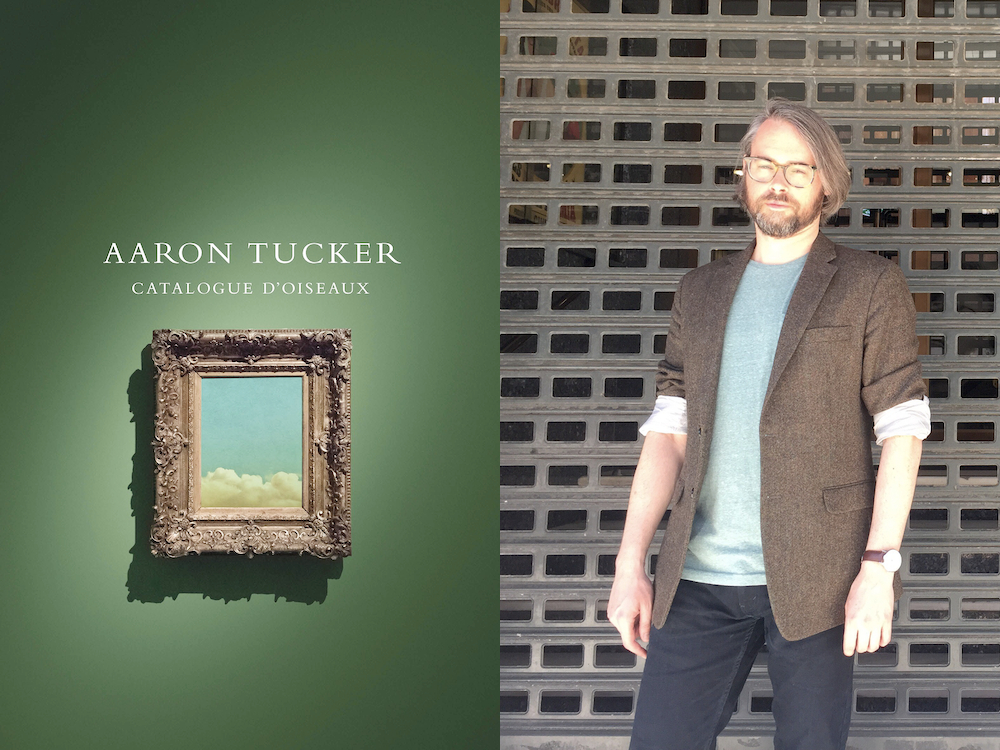

Happy Publication Day to Catalogue d’oiseaux by Aaron Tucker

Happy publication day to Aaron Tucker’s Catalogue d’oiseaux! We’re delighted to share this book-length lyrical, confessional love poem from the author of Irresponsible Mediums, especially during National Poetry Month. This expansive poem moves sensually through small, intimate spaces and the larger world alike. Traced through art, architecture, and the cultural life of various cities, this stunning celebration of love lives between geographies and chronologies as a kaleidoscopic gathering of the many fractals that make up a couple’s life.

“Tucker’s elegant lines, each a marvel, like the finest of lenses, draw us into exact focus, remind us of why we cascade trip fall head over heels at all,” writes Kirby, author of This Is Where I Get Off. “Here within the immensities of love we experience ourselves, trees, birds, streets, buildings, worlds, as bodies in every heightened, intricate detail, anew. My pilot light is aflame.”

We talked to Tucker about his practice—which includes daily walks, films, little libraries, and, of course, music—and about how Catalogue d’oiseaux came to fruition.

B*H: Why do you write?

AT: I usually start with a problem I am interested in responding to, sometimes spurred by a book, or a news article, or a conversation. More often than not it’s something I circle around for a while: my writing process involves a lot of thinking and reading before I commit to writing. Basically, I spend that time trying to figure out if there is enough material and energy to sustain me through a whole book.

I think my writing can be too cerebral at times, and is also why I found Catalogue d’oiseaux pretty different. First, I never really thought of what I was doing as poetry; in fact, at the time I was lamenting to my partner Julia that I wasn’t writing, that I felt dried out and unmotivated. Meanwhile, I was writing a small thing every day, stream of consciousness prose, when I woke up in the morning and sent to her while she was living in Germany and I was still in Toronto. Most often they took some sort of conceit, and spun it out for a few sentences or two, and I would hit send without editing.

I started to think of it as a book when I realized all the different places we had gone, all the art we had encountered, all the life we had lived together, and wanted a way to commemorate that. The first draft was a very shaggy 70 pages or so, but working with Karen Solie in editing carved out the excess that was cluttering the poem, and I think the leaner version in the book is the more interesting and strong for it.

B*H: Who, where, when, and what influences your writing?

AT: I always try to read as widely and intensely as I can when I’m writing, anything that I think might be related to what I’m working on; at the same time, I try to watch movies and seek out different pieces of art that I think are in the constellation of thought of the book. It is a sort of magpie approach, where I’m trying to keep my ears and eyes open for little unexpected side paths—often this takes the form of a recommendation from a friend, or something referenced in passing, that I never would have thought of on my own. In this way, I try to make myself as open as possible to as many different types of influences as possible, and let those shape the writing as I’m going through it. I don’t really outline a lot, nor do I do a ton of planning. I mostly give myself a goal each writing day and try to hit it: some days that is reading, some days that’s writing a short passage or through an idea, some days it’s editing what I wrote the day before.

Catalogue d’oiseaux was most overtly influenced by the different artworks I’ve been lucky to see over the last half decade, and by my relationship with Julia. It likely seems obvious but it’s very different being in love in your thirties and forties than in your teens and twenties: I’m a lot more calm now, and I have more of a sense of myself, which I think makes me, I hope, a more pleasant person to be with. The book is about that, and a lot about the accumulations that come with getting older, with being in other relationships, their success and failures, and emerging from it all into a place of happiness. I think then it’s important that the book includes places like Lausanne and Berlin, but also Lavington, where I grew up and where my family still lives.

B*H: What makes you happy?

AT: Happiness is a strange world to wrestle with in a global pandemic. Like most writers I suspect, a lot of how I feel and write now has been totally reshaped by a year in varying stages of Toronto lockdowns.

I really rely on my daily walks, in particular getting up early, before the city really starts moving, and walking through Cabbagetown, along some of the paths of Catalogue d’oiseaux. I’ve come to love the Necropolis and Riverdale Farm and the St. James Cemetery; it brings me a lot of joy to walk these spaces and notice the small changes that take place over a day.

The St. James Cemetery is especially delightful. If I’m lucky, I’ll get there not long after they open the gates, and I’ll be the first one to walk through. I’ve got to visit with a coyote that lives nearby a few times; there is also a fox that regularly shows up. In the winter, after a fresh snowfall, I can follow the tracks. In the spring, there are grown hawks and their young that circle and sound, so beautiful. There was one magical moment last summer, about 4 months into the pandemic where Julia and I were walking through the Necropolis and a huge hawk was sitting on one of the tombstones, then flew to another, each time stopping and watching us; at one point it flew right over top of us, maybe five feet above my head, and it was totally terrifying and gorgeous.

B*H: What helps you write?

AT: I have always needed music to write, usually cycling through concerts or classical albums, whatever sets me in a groove and gives me a bit of momentum. Early on in writing Catalogue d’oiseaux, I started to listen to Messiaen’s composition that the book’s title comes from. Messiaen is a very adventurous composer, one whose work I always find interesting but not always beautiful in a straightforward way. His Catalogue d’oiseaux is a stunning and original piano composition that is at turns cacophonous and melodic. What drew me to this piece in particular was that he dedicated it to his second wife Yvonne Loriod, who, to my mind, plays the definitive version of the piece (her version is on Youtube if interested); I was really drawn to the shared companionship and love in the making and playing of the piece. As for the piece itself I love how large and varied it is, a sprawling sort of non-description of birds and birdsong; a more straightforward composition would have maybe tried to mirror parts of the actual bird but the piece is instead capturing, I think, the movements, the sounds, the life of each bird; looking now at the Wikipedia I also see each section reflects a French province and that the sections then capture the birds within each province but also its inhabitants and landscapes, something that I think melds well with the poem. Too, I have always been drawn to lists and catalogues as forms of art, finding the logical wrangling of items and thoughts are always in tension with more abstract desires and life.

B*H: How did you know that your most recently written book was finished?

AT: I started a PhD! I do love my grad work at York University in the Cinema and Media Studies department. But I told myself when I started that I wouldn’t give up writing creatively and in many ways, starting school again after a dozen years away was a good push to get the manuscript done before I dove in. Then, once I was in the weeds of grad school, I would get edits from Karen and into conversations about poetry with friends, and it would be a much needed oasis, a place apart from the daily grind of PhD work.

But I’m not sure now if the book is completely done. I could see myself coming back to it again in ten years, and extending it.

B*H: Do you have a preference for fiction, nonfiction, or poetry in your reading or writing?

AT: Lately, I have been mostly reading whatever shows up in the free little libraries on my walks. Sometimes this means genre stuff, like John Le Carre, other times it’s an Eden Robinson novel. I’ll read almost anything. I’m a fast enough reader that I can usually move through books fairly quickly, but, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten far less precious about finishing books. If I’m not interested after a time, I’ll just send it back out for someone else!

B*H: Describe the sky where you are.

AT: It is slate and speckled with snow, and connected to all the other places of the world.

❧

As a bonus, we’re equally delighted to share not one, but two videos that Tucker recorded for readers, which you can watch and enjoy below:

Aaron Tucker was born and raised on traditional Syilx territory in Lavington B.C. and now lives in Toronto as a guest on the Dish with One Spoon Territory. His novel, Y (2018), was translated into French as Oppenheimer in 2020. He is also the author of two previous poetry collections, including Irresponsible Mediums: The Chess Games of Marcel Duchamp (Book*hug Press, 2017). He is currently a PhD candidate in the Cinema and Media Studies Department at York University where he is an Elia Scholar, a VISTA Doctoral Scholar, and 2020 recipient of the Joseph-Armand Bombardier Doctoral Scholarship.