One Book That Altered My Writing: An Author Roundtable

At Book*hug, we love to celebrate not only the work of our wonderful authors, but also the long tradition of artists and writers that helped inspire many of the books we publish today. For this edition of our Author Roundtable, Book*hug reached out to a number of our writers and asked them to select one book that has been particularly influential for their craft as readers themselves.

Introducing: Liz Worth (The Truth is Told Better This Way), Oisín Curran (Blood Fable), Stephen Cain (False Friends), Emily Anglin (The Third Person), and Erin Robinsong (Rag Cosmology). Together, this list showcases both the talents of its participants, and the diverse range of books whose stories shaped their own.

Picking a single book out a life-time of reading is no simple task. Read on to see some books that hold a special place in hearts and careers of the Book*hug family.

What is one book that forever altered the course of your writing?

Liz Worth: 1978 by Daniel Jones (Three O’Clock Press). I was influenced by its ugliness. I also read this book at a time in my life when it could really speak to me. Jones’ writing is so sparse, minimal, direct. It gets to the point and says so much with so little. There is something so physical about that book. It’s like a taut, undernourished muscle about to make a move. It inspired me to write from the body in all of its discomforts. To write about life as something unflattering and cold and disappointing.

Liz Worth: 1978 by Daniel Jones (Three O’Clock Press). I was influenced by its ugliness. I also read this book at a time in my life when it could really speak to me. Jones’ writing is so sparse, minimal, direct. It gets to the point and says so much with so little. There is something so physical about that book. It’s like a taut, undernourished muscle about to make a move. It inspired me to write from the body in all of its discomforts. To write about life as something unflattering and cold and disappointing.

Oisín Curran: So many, there are so many. Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch, for instance, or Woolf’s The Waves, or The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter, or Ursula LeGuinn’s Earthsea books, Beckett’s The Unnameable, Speak, Memory by Nabokov, Gods, Men and Ghosts by Lord Dunsany, Ficciones by Borges, Joyce’s Ulysses, The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, and on and on in my personal category of books that made me want to write and changed the way I write. But I’m going to say, if I must, Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day (New Directions). It is, on the one hand, an extremely unusual and innovative work, but at the same time completely suffused with the warmth of Mayer’s personality. It’s a book-length poem about a midwinter day in the 70s (I think). It’s epic, but domestic. It’s got literary references if you want literary references (it begins, like Ulysses, it’s clear antecedent, with the word “Stately”) but is also stuffed with all kinds of ephemera and drift. It’s high and low (Mayer trained as a classicist), funny and beautiful. So many great modernist books, like the works of Woolf, Joyce or Beckett are stunning, overwhelming, formidable. How can one follow in the wake of The Unnameable? There’s nothing more to be done. But, for me, Mayer’s poetry opened a path forward. Her approach isn’t programmatic or monumental, it doesn’t seek to exhaust the possibilities of its method. It’s loose when it needs to be loose, disciplined when it needs disciplined, arch when archness fits and then quickly casual and feels generous in spirit toward its readers and the writers (like me) that it inspires.

Oisín Curran: So many, there are so many. Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch, for instance, or Woolf’s The Waves, or The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter, or Ursula LeGuinn’s Earthsea books, Beckett’s The Unnameable, Speak, Memory by Nabokov, Gods, Men and Ghosts by Lord Dunsany, Ficciones by Borges, Joyce’s Ulysses, The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, and on and on in my personal category of books that made me want to write and changed the way I write. But I’m going to say, if I must, Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day (New Directions). It is, on the one hand, an extremely unusual and innovative work, but at the same time completely suffused with the warmth of Mayer’s personality. It’s a book-length poem about a midwinter day in the 70s (I think). It’s epic, but domestic. It’s got literary references if you want literary references (it begins, like Ulysses, it’s clear antecedent, with the word “Stately”) but is also stuffed with all kinds of ephemera and drift. It’s high and low (Mayer trained as a classicist), funny and beautiful. So many great modernist books, like the works of Woolf, Joyce or Beckett are stunning, overwhelming, formidable. How can one follow in the wake of The Unnameable? There’s nothing more to be done. But, for me, Mayer’s poetry opened a path forward. Her approach isn’t programmatic or monumental, it doesn’t seek to exhaust the possibilities of its method. It’s loose when it needs to be loose, disciplined when it needs disciplined, arch when archness fits and then quickly casual and feels generous in spirit toward its readers and the writers (like me) that it inspires.

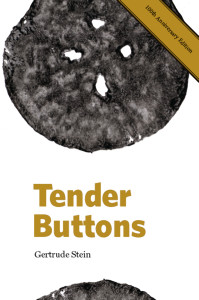

Stephen Cain: While David McFadden’s The Art of Darkness (1984) showed me the way of out lyricism to explore prose poetry, dark humour, and surrealism, and bpNichol’s The Martyrology (1972-1988) opened up many possibilities regarding the long poem, the use of pun, and concretism, the one book that has remained influential from the beginning of my career until now is Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914, reissued by Book*hug 2008).

Stephen Cain: While David McFadden’s The Art of Darkness (1984) showed me the way of out lyricism to explore prose poetry, dark humour, and surrealism, and bpNichol’s The Martyrology (1972-1988) opened up many possibilities regarding the long poem, the use of pun, and concretism, the one book that has remained influential from the beginning of my career until now is Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914, reissued by Book*hug 2008).

The radical parataxis of her lines, the constant surprise and resulting befuddlement of the relationship between her titles and body text, the idea of poetic portraits, the sly jokes, and her often hypnotic prosody—all of these elements changed the way I thought about poetry and the possibilities of the form. My first chapbook, a no(u)n (1997), with its portraits of “People,” “Places,” and “Things” was a direct homage to Stein’s division of Tender Buttons into “Objects,” “Food,” and “Rooms.” This sequence also appeared in my first book, dyslexicon (1998), and my next book, Torontology (2001), using what I learned from Stein about repetition in the construction of the long sequence “Pscycles” (in this case, anadiplosis). The influence of this relatively short, but extremely dense and evocative text, is still with me as “Stanzas” from my latest Book*hug book, False Friends (2017), is an allusive referential reduction of Stein’s “Rooms.”

Emily Anglin: The book that forever altered the course of my writing was The Vegetarian by Han Kang (Random House).

Emily Anglin: The book that forever altered the course of my writing was The Vegetarian by Han Kang (Random House).

In prose that is both lucid and poetic, Kang’s novel starts quietly, with the banal elements of the everyday somehow upended by a character’s seemingly inconsequential choice about personal consumption: the choice to not eat meat. The book’s first sentence (“Before my wife turned vegetarian, I thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way”) is at once the soft-speaking and the stick, a hint of the meditation on the thin line between remarkable and remarkable, between domesticity and violence—both physical and metaphysical—that the book becomes.

Formally, the novel is a psychological thriller and a philosophical shocker, told through the disintegration of the main character. I read Kang’s book while writing my book of short stories The Third Person; the glimpses Kang’s story affords of the void visible around the edges of the quotidian was an inspiration for my interest in finding the unfamiliar and the unsettling in the familiar. In Kang’s book, people are defined by what they do, but then the main character stops doing anything, which in this world registers like a kind of existential refusal; this disconnect between occupation and existence fascinates me and serves as a touchstone for the themes of my own fiction.

Erin Robinsong: I’m sitting on a train and a guy is talking on his phone very loudly about a foot from my head, so I’ll try to be coherent. Anyway, since I want to talk about voice, maybe I deserve it.

Erin Robinsong: I’m sitting on a train and a guy is talking on his phone very loudly about a foot from my head, so I’ll try to be coherent. Anyway, since I want to talk about voice, maybe I deserve it.

I am often reading ‘the one book’ that forever alters the course of my writing. I get antsy with books when it’s not that kind of book – a terrible thing to ask of books generally, and a habit I’m trying to let die! Right now it’s Alice Notley’s book of essays, Coming After (University of Michigan Press), but looking back, there’s a series of books, certain books at certain times, that have unlocked what I felt was possible, and necessary, what I desired but had no language yet for. When I was in high school it was Richard Brautigan and Francesca Lia Block, and when I was in my early 20s, it was Anne Carson (Autobiography of Red first, then everything she wrote), and then Dionne Brand (Bread out of Stone, in particular) Lisa Robertson (R’s Boat, in particular), Ariana Reines, Claudia Rankine, Maggie Nelson. They and others all altered me and my writing. Right now it’s Alice Notley, who I keep coming back to, who consistently says the thing I need to hear at some precise moment— which right now is about voice. Yesterday, I read this and it altered everything (and I know you asked for one book, but since that depends when you ask, now it’s this): “…the voice of the poem doesn’t seem to come from the brain, i.e. the part of the person that willfully imposes pre-intentioned meanings or constructions. I’ve asked various poets where in or around the body the poem voice comes from for them and for example Anne Waldman said the voice comes from deep in the chest and Allen Ginsberg said that for him it is the throat and that he actually feels his vocal cords vibrate when he writes. I myself used to hear the voice come from just outside my forehead on the right side; now I’m not sure, different places, something in the mouth or maybe from the eyes.” In part, I keep coming back to Notley because of something I’m trying to learn about voice that she is an utter (utter) master of, or maybe channel for, or truster of. I learn most about that through her poems, but it’s instructive in a different way to read her essays on poetry. They’re generously course-altering.

About the Authors

Photo credit: Shawn Nolan

Liz Worth is the author of six books, including Treat Me Like Dirt: An Oral History of Punk in Toronto and Beyond, and No Work Finished Here: Rewriting Andy Warhol (BookThug, 2016; nominated for the ReLit Award for poetry). She was born and raised in Toronto, where she continues to reside.

Photo credit: Sarah Faber

Oisín Curran grew up in rural Maine. He is the author of Mopus (2008) and was named a “Writer to Watch” by CBC: Canada Writes. Curran lives in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, with his wife and two children.

Stephen Cain is the author of a dozen chapbooks and five full-length collections of poetry. Cain lives in Toronto, where he teaches avant-garde and Canadian literature at York University.

Stephen Cain is the author of a dozen chapbooks and five full-length collections of poetry. Cain lives in Toronto, where he teaches avant-garde and Canadian literature at York University.

Photo credit: Matthew Strohack

Writer and freelance editor Emily Anglin grew up in Waterloo, Ontario, and now lives in Toronto. Prior to her graduate studies, she studied English at the University of Waterloo. The Third Person is her debut book.

Credit: Bernardo Fernandez

Erin Robinsong is a poet and interdisciplinary artist. Originally from Cortes Island, Erin lives in Toronto & Montréal. Rag Cosmology is her debut collection.