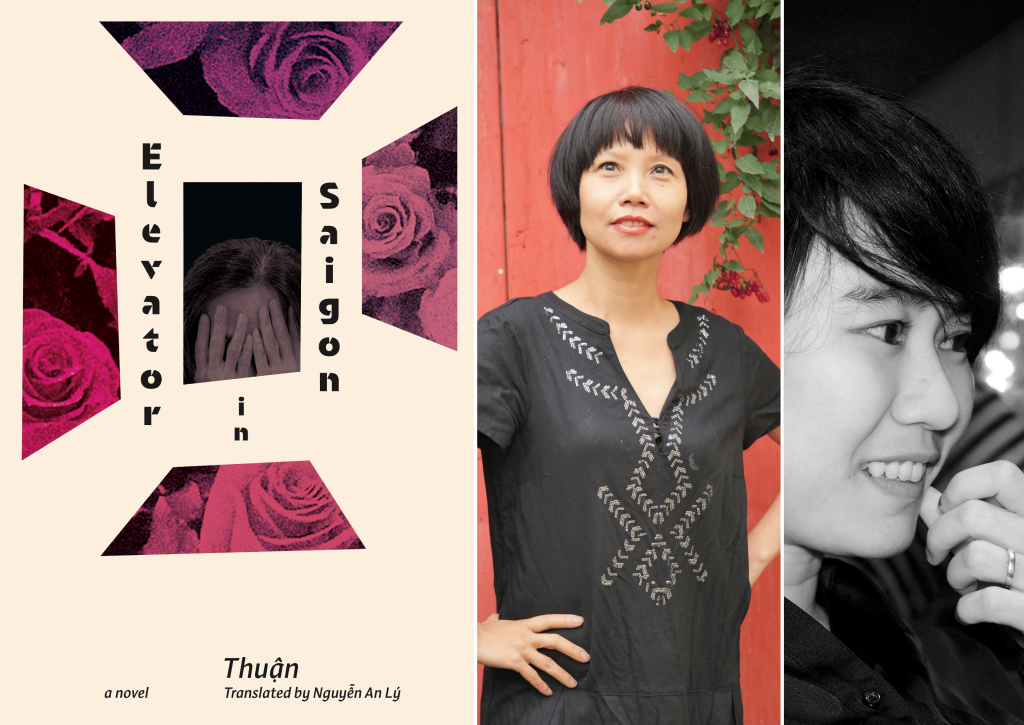

Winter/Spring 2024 Fiction Preview: Elevator in Saigon by Thuận, translated by Nguyễn An Lý

The final title in our Winter/Spring 2024 Fiction Preview is Elevator in Saigon by Thuận, translated by Nguyễn An Lý!

From the author of Chinatown comes a personal and political, tragic and bitingly satirical, ethereal journey through Hanoi, Saigon, Paris, Pyongyang, and Seoul.

A Vietnamese woman living in Paris travels back to Saigon for her estranged mother’s funeral. Her brother had recently built a new house in Saigon, and staged a grotesquely lavish ceremony for their mother to inaugurate what was rumoured to be the first elevator in a private home in the country. But shortly after the ceremony, in the middle of the night, their mother dies after mysteriously falling down the elevator shaft.

Following the funeral, the daughter becomes increasingly fascinated with her family’s history, and begins to investigate and track an enigmatic figure, Paul Polotski, who emerges from her mother’s notebook. Like an amateur sleuth, she trails Polotski through the streets of Paris, sneaking behind him as he goes about his usual routines; meanwhile, she researches her mother’s past—zigzagging across France and Asia—trying to find clues to the spiralling, deepening questions her mother left behind unanswered—and perhaps unanswerable.

Still banned in Vietnam, Elevator in Saigon is a suspenseful novel that is part detective story, historical romance, postcolonial ghost story, and a biting satire of life in a communist state.

We’ve selected an excerpt from Elevator in Saigon to share today! The book will be released on July 9, 2024, and is available for pre-order from our online shop or from your local independent bookstore.

My mother died on a night of torrential rain. A night of unseasonal rain in 2004. In such a freak accident that our language probably had no word to name it. Mai, my brother, my only brother, had just constructed for himself yet another multistory house, this time with a home elevator, said to be the very first in the whole country. Such a momentous event called for celebration, so he bought my mother a plane ticket to Sài Gòn. Only after her inaugural push of the elevator button—he insisted—only after her round from the ground floor to the top and back, could his guests avail themselves of the device. Among said guests even were members of the press, print as well as TV. Such events always followed a predictable script, but I still spent the evening after my mother’s funeral watching a sixty-minute DVD and flipping through a hundreds-strong album of photos of the inauguration, and then another sixty-minute DVD and another hundreds-strong album of that day’s funeral, which I had attended from start to finish.

I’d realized at a very young age that my mother had always been something of a stand-out, whether alone or in the middle of a crowd, at a party committee meeting or one for the local civil unit, as a recipient of a certificate of merit or bestower of a prize, and now, on the family altar, she was a stand-out among the dead, her dead, her parents and in-laws and elder siblings. And her husband. My brother had taken care to put their portraits side by side, nestling behind a vase of red roses, but they still looked like two strangers who’d never signed a marriage license, never lived together for two decades, never birthed two children (my brother Mai and me) who gave them two grandchildren (Mai’s daughter Ngọc and my own son Mike). That evening, I tried and tried to evoke a family scene from our former life, but in vain; I could picture my mother’s face clearly, but had to refer again and again to my father’s portrait, wreathed by red roses and thick incense smoke. He had died ten years earlier.

We had dinner together, my brother and I and the two children. Mai said, “Those inspectors from the German elevator company looked into every corner they could but couldn’t pinpoint the cause of the accident. The elevator worked perfectly well during the inauguration, perfectly well for the next three days, and perfectly well after the accident, so they simply couldn’t comprehend how the car could have stayed stationary down below, oblivious to her call, when mother fell into the shaft, all the way from the top to the ground floor. And I can’t comprehend what on earth mother could have been doing on the top floor at such an hour, in such rain, for such a long time.”

____________________________________________________________________________________________

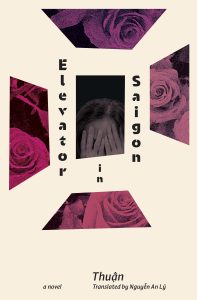

Thuận was born in 1967 in Hanoi. She studied at Pyatigorsk University (Russia) and at la Sorbonne in Paris. She is the author of ten novels and a recipient of the Writers’ Union Prize, the highest award in Vietnamese literature. 7 of her novels were translated and published in France.Chinatown, her debut novel in English, won a PEN Translates Award, the 2023 ALTA National Translation Award, and was shortlisted for the 2023 Republic of Consciousness Prize. She currently lives in Paris.

Nguyễn An Lý lives in Hochiminh City. She has over twenty translations into Vietnamese, published under various names and in various genres, including authors such as Margaret Atwood, Donna Tartt, Kazuo Ishiguro, Richard Flanagan, J. L. Borges, and the poetry in The Lord of the Rings. As an editor, she has worked on translations from Nabokov, A. S. Byatt, Roland Barthes, Joseph Campbell, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and Liu Cixin, among others. Chinatown by Thuận, her debut translation into English, won an English PEN Translates Award and the 2023 ALTA National Translation Award in Prose. She co-founds and co-edits the independent online Zzz Review.