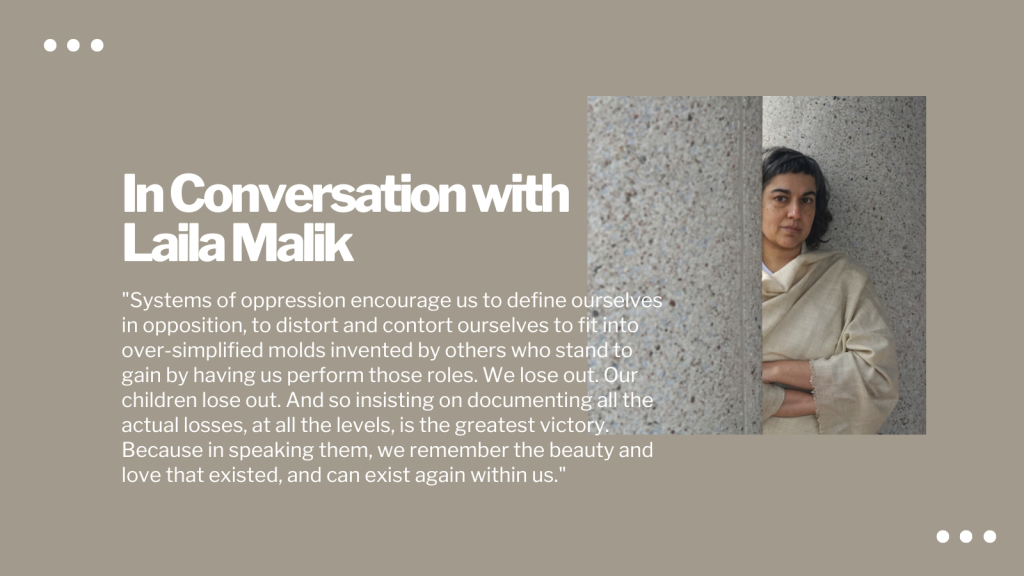

“A constant movement, an ongoing development”: In Conversation with Laila Malik

Today, we are delighted to be in conversation with Laila Malik, author of archipelago. Malik’s lyrical poems intertwine histories of exile and ecological devastation. Beginning with a coming of age in the 80s and 90s between Canada, the Arabian Gulf, East Africa and Kashmir, they subvert conventions of lineage, instead drawing on the truths of inter-ethnic histories amidst sparse landscapes of deserts, oceans, and mountains. They question why the only certainties of “home” are urgency and impossibility.

We talked to Malik about her writing process, her interest in loss, and the concept of home.

Book*hug: archipelago is your debut collection. Can you tell us a little bit about how you came to write it? Was there a long process of gathering materials? Did it come together quickly?

Laila Malik: The truth is that this collection was at least 30 years in the making, in the sense that the experiences that informed it began then. But the process of writing it was textured and incremental; I wasn’t imagining a poetry collection when I wrote some of these pieces, I was just trying to make sense of a very complex physical, historical, and emotional landscape. There were so many aspects to our realities that we didn’t quite have words for, and so many wary silences. But finally, it was Chelene Knight’s Advanced Poetry workshop in 2017 that brought the possibility of a full collection into focus and possibility. As a non-MFA grad, writing has always simultaneously been an intimate, protected space and one in which my imposter syndrome is in full effect. Chelene cracked it wide open for me and others like me, and taught me how to imagine differently. The rest flowed, working at different points with Nasser Hussain and Shazia Hafiz Ramji, both of whom are brilliant and beautiful minds, and whose questions and nudges sharpened the individual words and brought the bigger narrative flow into focus.

archipelago interweaves episodes of acute loss—the passing of a sibling, a partner—with meditations on broad legacies of loss—a lineage of migrations which have fractured familial and cultural life. Are you interested in the resonances between these two forms of loss? How do they come together for you?

I’m absolutely interested in the resonances between those forms of loss, particularly with respect to how we document, remember and build from them. It’s clichéd to say it in our cultural moment of over-sharing, but the loss that comes with silence is to me the greatest tragedy. The subversive and the subaltern micro-stories inform the bigger pictures, and when we lose or bury them it’s so easy to veer off-track as families, communities and peoples, so easy to start telling half-truths about ourselves that those who come after us have no choice but to believe.

But there’s such a grave danger in those half-truths, so much power we relinquish and a kind of intra-cultural biodiversity lost. For diasporas, this is venomous, because we’re inclined to seek and lean into singular, linear, flattened ideas of our own supposedly authentic identities, rather than celebrating our specific, situated complexities. Systems of oppression encourage us to define ourselves in opposition, to distort and contort ourselves to fit into over-simplified molds invented by others who stand to gain by having us perform those roles. We lose out. Our children lose out. And so insisting on documenting all the actual losses, at all the levels, is the greatest victory. Because in speaking them, we remember the beauty and love that existed, and can exist again within us.

Dust pervades these poems. It seems to show up in every nook and cranny. What purpose does it serve?

Dust is comprised of fine particles of earth matter. I want readers to feel the constant, immanent presence of earth in all this human being. It also simultaneously implies stillness and transformation, the tremendous slowness of geologic time that brought us all here, that will outlive us all. I want readers to be reminded of that, to be pulled from mundane, myopic immediacies, to see and understand themselves in the widest lens possible.

archipelago is interested in finding a language for diaspora, or at least pointing to the difficulty of doing so. Diaspora itself is referred to as “a fetid, unfurling language.” What did you have in mind when writing this line?

There is simultaneously such shame and such pride in diaspora. We hearken back to former glories, the “kodachrome era with brighter flavours, better fashion, more precise truths,” as a way of consoling ourselves for perennially feeling lost and unmoored by the original departures, and in the here and now. And yet diaspora is in fact a process as well as a state of being, hence the idea of “unfurling”—a constant movement, an ongoing development. And one so rich and fertile, even in the midst of its pain, hence “fetid.” Fetor can imply decay, the breakdown of organic matter and the birth of new life. That’s diaspora. I’m interested in journeying the wonders of that new life with an open heart, without losing sight of the many interwoven lineages that brought us to this point.

The image of a person facing eastward recurs a few times throughout the poems. It is reminiscent of how, in both Islam and Judaism, there are traditions of facing towards a holy site during prayer. I wonder if the lost homeland takes on the status of the holy: the aura of a thing that is known and yet out of reach; a place that exists more spiritually than materially.

The lost homeland(s) absolutely take on a holy hue, and the rituals we associate with them also become sacrosanct. And there is something so terribly dangerous in that. Because the actual physical homelands and the holy sites are themselves constantly in a state of flux. In a search for the secure constancies we diaspora often feel we lost, many of us reach for originary practices to feel connected to something eternal, which can be beautiful and fulfilling. But it can also turn into rigid preoccupations with form, undergirded with a patchy or selective memory of why and how those practices came into effect, the spirit of them, so to speak. And in that process, turning eastward loses all but the most superficial meaning, all the easier to control those seeking solace in spirituality.

The concept of home, and the difficulty in pinning that down, is a focus throughout the collection. “beware the person without a country—,” you write, “she has no country to lose.” This line is sombre yet freeing at the same time. Do you see statelessness as a rich place from which to write? Does it offer unique possibilities?

Statelessness could certainly be a rich place from which to offer crucial perspectives on some of the failures of the colonial, Westphalian system, but I would caution against romanticizing or fetishizing it. And I would clarify that I don’t write from a place of “statelessness”—I’m a settler on Turtle Island, with all the privilege that affords. But I write from a place related to poet Safia Elhillo’s novel-in-verse Home is Not a Country, among many other brilliant writers. Access to “status” within a state brings many benefits necessary to survival today, but it doesn’t automatically solve the home problem, not when systemic racism still informs these state structures, and not when we remain “uncomfortably perched on someone else’s burial ground.” There’s so much deep work for diasporas to do around building home, ethically and sustainably, and in right relation with Indigenous and non-Indigenous brethren.

“Archipelago” is defined at the beginning of the book as “a cluster, collection or chain of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.” It is also, of course, the title. How does this image tie the collection together for you as a whole?

I want readers of archipelago to experience granularity with each individual piece, and each of the four epochs in which they occur. And then I want them to zoom out and slowly see how they are connected and interdependent in visible and submerged ways, in the context of this specific narrative but also in the context of their own stories, and their own relationality to the lands and lineages they inhabit. And with that perspective, I would love for us all to re-imagine who we are to ourselves, to each other, and to this planet, and proceed in radically different ways, to “turn all this breaking into something beautiful.”

Laila Malik is a desisporic settler and writer in Adobigok, traditional land of Indigenous communities that include the Anishinaabe, Seneca, and Mohawk Haudenosaunee, and Wendat. Her work has been widely published in magazines and journals, including Contemporary Verse 2, Canthius, The New Quarterly, Ricepaper, Qwerty, Room, Sukoon, The Bangalore Review, and Archetype. Malik’s essays have been long-listed for five different creative non-fiction contests, and she was a fellow at the Banff Centre for Creative Arts in 2021.