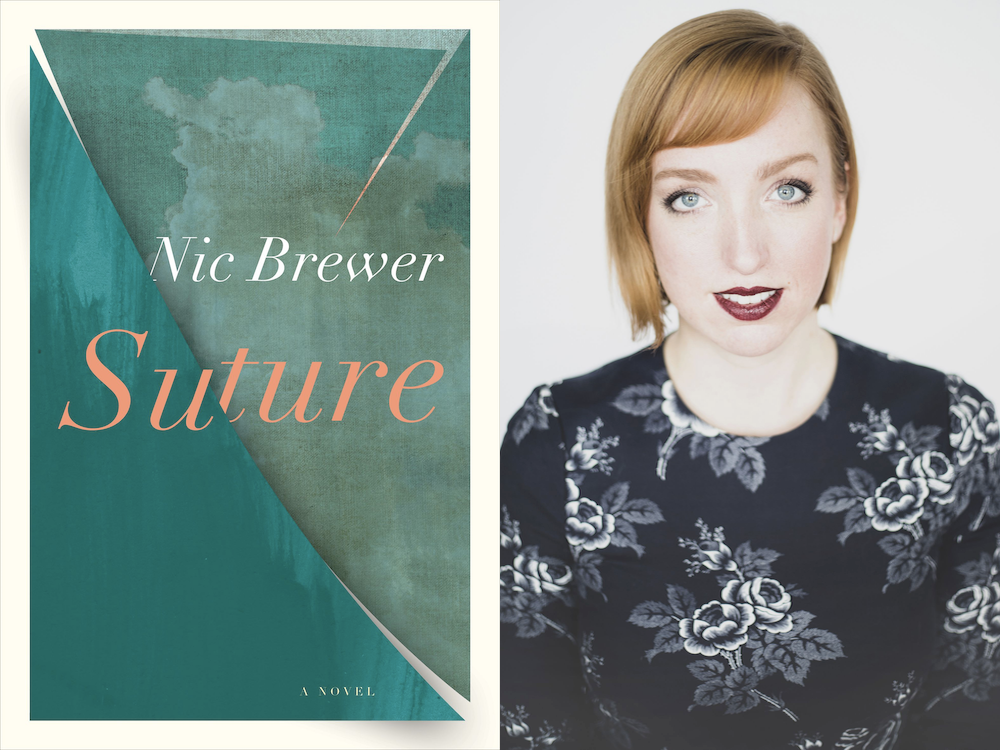

Fall Fiction Preview: Suture by Nic Brewer

It’s time to meet the Fall 2021 authors and their books! We’ll be diving more deeply into the books we introduced in our Fall 2021 season reveal, previewing individual titles. Stay tuned on the blog for exclusive excerpts and thoughts from the authors, and if you haven’t already done so, follow Book*hug on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter. We look forward to sharing these seven amazing books with you!

Our series of sneak peeks continues with Suture, by Nic Brewer, which John Elizabeth Stintzi calls “a fleshy, flashy, not-for-the-faint-of-heart tale that poetically reimagines artmaking into the gory-yet-tender body horror that it has—perhaps—always figuratively been.” Suture shares three interweaving stories of artists tearing themselves open to make art. This exciting debut novel is a highly original meditation on the fractures within us, and the importance of empathy as medicine and glue.

To make her films, Eva must take out her eyes and use them as batteries. To make her art, Finn must cut open her chest and remove her lungs and heart. To write her novels, Grace must use her blood to power the word processor. Each artist baffles their family, or harms their loved ones, with their necessary sacrifices. Eva’s wife worries about her mental health; Finn’s teenager follows in her footsteps, using forearms bones for drumsticks; Grace’s network constantly worries about the prolific writer’s penchant for self-harm, and the over-use of her vitals for art.

“Suture is a daring, visceral debut that examines the painful side of the creative process,” writes Catriona Wright. “Blending body horror with meditations on love, art, and forgiveness, this novel will startle and captivate you.”

We’re delighted to share an introductory video from Brewer. Enjoy!

In addition, we’ve selected an excerpt from the book, which you can read—and also enjoy!—below. Suture will be released on September 21st, 2021, and is available now for pre-order, either from our online shop or from your local independent bookstore.

“A map of your journey”

The women were three storeys tall and the police were trying to shatter the crowd. They couldn’t find the projector. So these twenty-foot-tall cunts and bushes played the whole time, right on the side of the station. The baton sticks so appropriately phallic while these ghostly Amazonian women sat naked and read police reports to each other over a pot of peppermint tea. Some days I hate that that’s my legacy: cunts and bushes and a blushing riot. Imagine, your edgy undergrad thesis haunting you for the rest of your career. I love it, I love what we did… but I wish it didn’t show up on every list of great feminist film projects. They have all been feminist, you know? Not just the one with naked giantesses.

A woman falls in love with women.

My right eye was still in the camera when they arrested me. They knocked off the eye patch when they pushed me into the back—you should have seen it. Have you? An empty eye socket? It’s disgusting. Everyone thinks it’s going to be black, but they don’t remember the blood. It crusts under the eye patch after a while, this ring of scabby brown right where your makeup would smudge. Clumping the eyelashes. And the eyelid sags dreadfully, with the extra weight of the blood, the eyelashes. Into the concavity, a little wrinkly, too soft without the eye there to support it. But if you lift it up out of the way, the inside is more white than anything. A slick white with smears of the brightest red. Not like when you bleed; brighter. Almost translucent. Shiny. It’s not dark at all in the socket—it’s eerily light. Light and wet.

A woman falls in love with injustice.

People started yelling “cunt” at me everywhere I went. It felt like I had accomplished something.

A woman falls in love with rage.

I learned to fight after the third time someone tried to take my eyes.

A woman falls in love with justice.

My aunt’s best friend gave me her son’s camera for my thirteenth birthday, but she didn’t tell me how to use it. She didn’t tell me anything. Her son had killed himself at film school a few months earlier, and how do you tell someone that? Maybe the way I just told you, or maybe you hand over a used $3,000 video camera and say “careful, honey” and “sorry we don’t have the box anymore,” and you let the memory harden just a little more and you hope it doesn’t happen again. This was before the internet, remember. There was nowhere for me to go to learn how to use a real camera. But there was a movie being filmed just around the corner from my friend’s house that summer, and I snuck onto the set every day to try to catch the directors in the act. Eventually I saw them, calmly popping their eyes into their palms, slipping them into their cameras; there was a lot more blood when I tried it.

A woman falls in love with potential.

Nic Brewer is a writer and editor from Toronto. She writes fiction, mostly, which has appeared in Canthius, the Hart House Review, and Hypertrophic Literary, among others. She is the co-founder of Frond, an online literary journal for prose by LGBTQI2SA writers, and formerly co-managed the micropress words(on)pages. She lives in Kitchener, ON, with her partner and her dog. Suture is her first book.