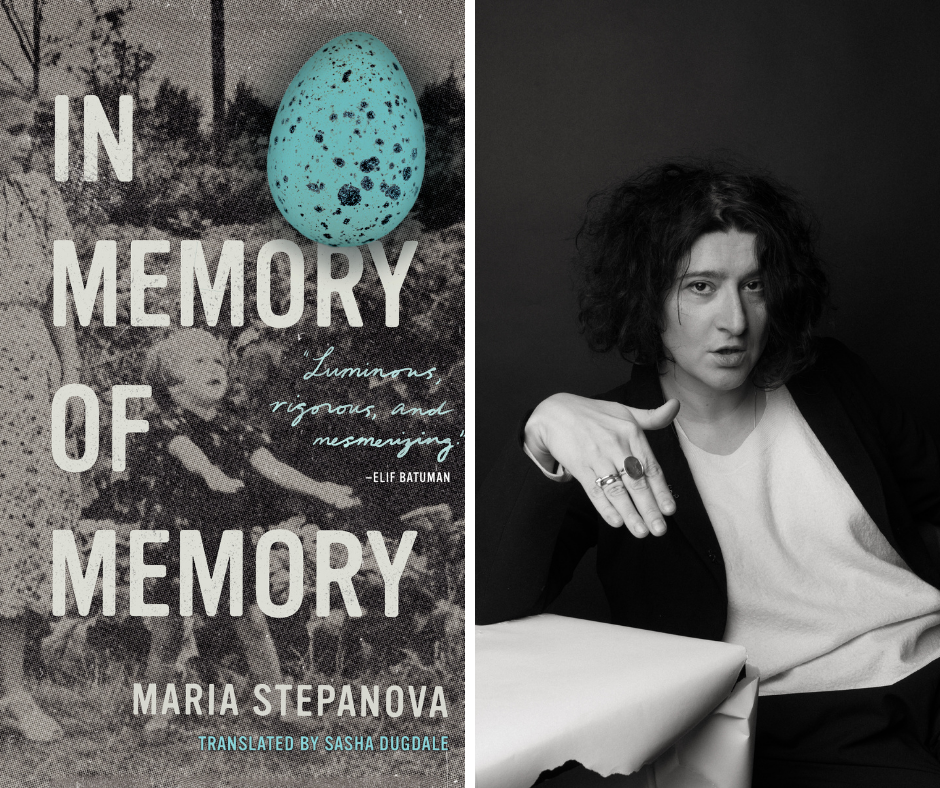

Happy Publication Day to Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, Translated by Sasha Dugdale

Happy Publication Day to Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, translated from the Russian by Sasha Dugdale! Already published in 17 territories, we’re thrilled to introduce this remarkable work of documentary fiction to Canadian readers.

In Memory of Memory tells the story of how a seemingly ordinary Jewish family somehow managed to survive the myriad persecutions and repressions of the last century. Dipping into various forms, including essay, fiction, memoir, travelogue, and historical documents, In Memory of Memory is imbued with rare intellectual curiosity and a wonderfully soft-spoken, poetic voice. Elif Batuman, author of The Idiot and a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist, calls the book a “luminous, rigorous, and mesmerizing interrogation of the relationship between personal history, family history, and capital-H History… In Memory of Memory has that trick of feeling both completely original and already classic.” Andrew McMillan, award-winning author of Playtime, calls it a “book to plunge into.”

We’re far from the only ones excited about In Memory of Memory. The Guardian has dubbed 2021 “the year of Stepanova.” The New York Times calls the book a “kaleidoscopic, time-shuffling look at one family of Russian Jews throughout a fiercely eventful century.” The New Yorker calls it “sensitive and rigorous.” And the Wall Street Journal writes that “[t]his is an erudite, challenging book, but also fundamentally a humble one, as it recognizes that a force works on even the most cherished family possessions that no amount of devotion can gainsay.” (It was also excerpted in The Paris Review.) In its native Russia, In Memory of Memory won the 2018 Bolshaya Kniga Award and the 2019 NOS Literature Prize, and has now been published in over seventeen territories. Stepanova herself has received several Russian and international literary awards, including the Andrey Bely Prize and the Joseph Brodsky Fellowship.

Please enjoy an excerpt from In Memory of Memory, which you can now order from our online shop, or from your local independent bookstore. Congratulations, Maria and Sasha!

Her apartment now stood silent, stunned and cowering, filled with suddenly devalued objects. In the bigger room television stands squatted grimly in each corner. A huge new fridge was stuffed to the gills with icy cauliflower and frozen loaves of bread (“Misha loves his bread—get me a couple of loaves in case he comes over”). The same books stood in lines, the ones I used to greet like family members whenever I went around. To Kill a Mockingbird, the black Salinger with the boy on the cover, the blue binding of the Library of Poets series, a grey-bound Chekhov set, the green Complete Works of Dickens. My old acquaintances on the shelves: a wooden dog, a yellow plastic dog, and a carved bear with a flag on a thread. All of them crouched, as if preparing themselves for a journey, their own stolid usefulness in sudden doubt.

A few days later, when I sat down to sort through papers, I noticed that in the piles of photographs and postcards there was hardly anything written. There were hoards of thermal vests and leggings; new and beautiful jackets and skirts, set aside for some great sallying forth and so never worn and still smelling of Soviet emporia; an embroidered men’s shirt from before the war; and tiny ivory brooches, delicate and girlish: a rose, another rose, a crane with wings outstretched. These had belonged to Galya’s mother, my grandmother, and no one had worn them for at least forty years. All these objects were inextricably bound together, everything had its meaning only in the whole, in the accumulation, within the frame of a continuing life, and now it was all turning to dust before me.

In a book about the working of the mind, I once read that the important factor in discerning the human face was not the combination of features, but the oval shape. Life itself, while it continues, can be that same oval, or after death, the thread of life running through the tale of what has been. The meek contents of her apartment, feeling themselves to be redundant, immediately began to lose their human qualities and, in doing so, ceased to remember or to mean anything.

I stood before the remnants of her home, doing the necessary tasks. Bemused at how little had been written down in this house of readers, I began to tease out a melody from the few words and scrappy phrases I could remember her saying: a story she had told me; endless questions about how the boy, my growing son, was doing; and anecdotes from the far-off past—country rambles in the 1930s. The woven fabric of language decomposes instantly, never again to be felt between the fingers: “I would never say ‘lovely,’ it sounds so terribly common,” Galya admonished me once. And there were other prohibited words I can’t recall, her talk of one’s people, gossip about old friends, the neighbours, little reports from a lonely and self-consuming life.

I soon found that there was in fact much evidence of the written word in the apartment. Among the possessions she kept till her dying day, the possessions she often asked for, sometimes just to touch with her hand, were countless used notebooks and diaries. She’d kept a diary for years; not a day passed without her scribbling a note, as much a part of her routine as getting out of bed or washing. These diaries were stored in a wooden box by her headboard and there were a lot of them, two full bag loads, which I carried home to Banny Pereulok. There I sat down at once to read them, in search of stories, explanations: the oval shape of her life.

Maria Stepanova, born in Moscow in 1972, is one of the most powerful and distinctive voices of Russia’s first post-Soviet literary generation. An award-winning poet and prose writer, essayist, and journalist, Stepanova is the author of ten poetry collections and three books of essays. Her poems have been translated into numerous languages including English, Italian, German, French, and Hebrew. She has received several Russian and international literary awards, including the prestigious Andrey Bely Prize and Joseph Brodsky Fellowship. Her novel In Memory of Memory is a documentary novel that has been published in over 17 territories. It won the 2018 Bolshaya Kniga Award, an annual Russian literary prize presented for the best book of Russian prose, and the 2019 NOS Literature Prize. Stepanova is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the online independent crowd-sourced journal Colta.ru, which covers the cultural, social and political reality of contemporary Russia, reaching audiences of nearly a million visitors a month.

Poet, writer, and translator Sasha Dugdale was born in Sussex, England. She has published five collections of poems with Carcanet Press, most recently Deformations, shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize 2020, and an Observer Book of the Year 2020. She won the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem in 2016 and in 2017 she was awarded a Cholmondeley Prize for Poetry. She is former editor of Modern Poetry in Translation and is Poet-in-Residence at St John’s College, Cambridge (2018–2021).