Kicks Just Keep Getting Harder to Find: In Conversation with Stephen Cain

False Friends is the first full-length poetry collection from Stephen Cain in more than ten years. In it, he takes inspiration from the linguistic term “false friends”—two words from different languages that appear to be related, but have fundamentally different meanings. In this book are poems both humourous and unforgiving that Cain uses to explore errors, misapprehensions, and mistranslations and offer insights into the “secret operations” hiding within everyday language.

These poems spin punk with pastoral, comic book with lyric, the misunderstood with the obvious. And at its core, False Friends is a thought-provoking investigation of the power of poetry as political discourse.

Sedimentary civilization,

in a purple peak.

Encircled by today’s tracks,

Juvenalian adolescence,

urinary undergrowth, Orientalist oaks.

Venereal seeds on a mattress of weeds—

golden memories of midday.

Moonshine discovered.

(“Or The Valley”)

BookThug Intern Melissa Myers sat down with Stephen to discuss False Friends and his experience writing this enthralling collection of poetry over the last ten years.

❧

Melissa Myers: What’s one thing you want to tell readers about False Friends?

Stephen Cain: That translation is liberating. Once the anxiety of fidelity to source material is renounced then the gates are open. Eventually I came to realize that every attempt at writing is a form of translation—of taking experience, emotion, cognition, and transforming/translating it into text.

MM: What inspired False Friends?

SC: My last two collections, I Can Say Interpellation and American Standard/Canada Dry were explicitly political and perhaps a tad histrionic in their desire to use poetry as a form of resistance. Frustrated by the (seeming) inefficacy of writing as a site of political change, I decided to go back and explore the mechanics and micro-syntactic elements of language (as I did in my first two books, dyslexicon and Torontology). What made aesthetic language work? What is the essence of “the poetic”? This time, however, I began by revisiting my adopted poetic parents bpNichol and Gertrude Stein, and tinkering with their inspiring texts Allegories and Tender Buttons, which resulted in the two longest sections of False Friends: “Etc Phrases” and “Stanzas”. At the same time I was heavily involved with teaching, primarily in the fields of Canadian Literature and the European Avant-garde, and re-engaging and analyzing the writing of poets from those areas resulted in “Mod Cons”, “Zoom” and “Proverbs for the Jilted Generation”.

MM: What are the most rewarding and most challenging aspects of writing for you?

SC: When the writing is going well, when I hit on the right sound effect, the illuminating pun, the conceptual framework the poem is going to explore, it is almost intoxicating. There is a real neurochemical pleasure akin to ekstasis. So writing might just be one of my addictions, albeit a less harmful one (debateable?). The challenges? Well, like most addictions, one dose is seldom enough, and you can’t write the same poem over and over again (well, at least I can’t). Kicks just keep getting harder to find.

MM: How did you decide on False Friends as a title? Did you have an alternate title at any point?

SC: The original title was Transition, attempting to reflect a change of direction in my writing and life, but it eventually didn’t seem as engaging as the present title. I also toyed with the idea of calling the collection as a whole Idiosyntactic which is the title of one of the sequences in the book.

MM: How long did it take you to complete False Friends? Were there any obstacles?

SC: False Friends collects writing over the last ten years, so the main obstacle was trying to determine what all these long sequences had in common so that I could order and envision the collection as a cohesive whole. There was an epiphanic moment when I realized that, in one way or another, all the writing involved translation.

MM: Was there any difference in procedure between writing your last book, and this one?

SC: Every one of my poetic sequences over the last 25 years has been written under a different constraint (whether that be conceptual, metrical, acoustic, numerical and so on). This collection continues to play with various constraints, but add the idea of re-imagining and re-writing pre-existing texts and images.

MM: What was the process of creating and deciding on the images in the book?

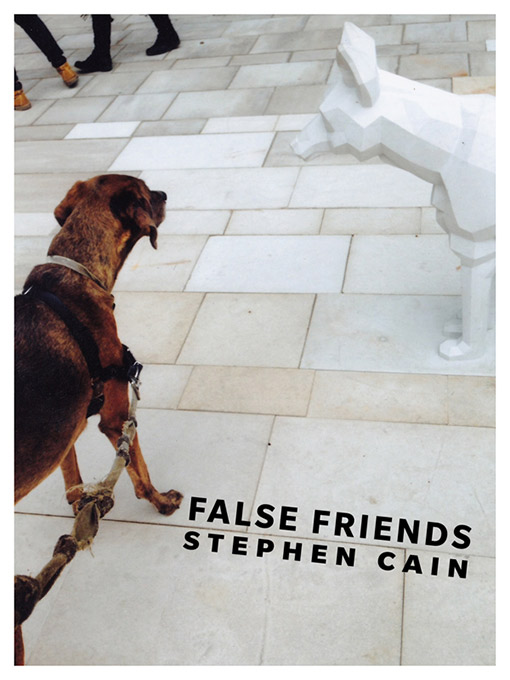

SC: I’m led more by the ear and thought-association than I am by image so I don’t have much to say about the imagery of the poetry (that is, in respect to Pound’s poetic divisions I’m more of a poet of melopoeia and logopoeia than phanopoeia). But I can say that the photograph on the cover was taken by the artist-writer Sharon Harris, and that, when I first saw it, it encapsulated perfectly so many of the issues that I was exploring: art versus life; loyalty and fidelity versus misdirection and misapprehension; friendship and companionship; and, translation and constraint.

MM: What song is definitely on your writing playlist?

SC: Too many to name over the decade, but Miles’s Complete Jack Johnson Sessions was in heavy rotation during the editing and assemblage of False Friends.

MM: What’s the next title on your reading list right now?

SC: As I read multiple texts concurrently I’m looking forward to reading Jordan Abel’s first three books, revisiting works by Liz Howard, Fenn Stewart, and Shannon Maguire, and starting my annual read-through of Nichol’s The Martyrology.

❧

Order your copy of False Friends here.

Credit: Sharon Harris

Stephen Cain is the author of a dozen chapbooks and five full-length collections of poetry, including dyslexicon (1998), American Standard/Canada Dry (2005), I Can Say Interpellation (BookThug, 2011), and Etc Phrases (BookThug, 2014). His academic publications include The Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages (co-written with Tim Conley; 2006) and a critical edition of bpNichol’s early long poems, bp: beginnings (BookThug, 2014). Cain lives in Toronto, where he teaches avant-garde and Canadian literature at York University.