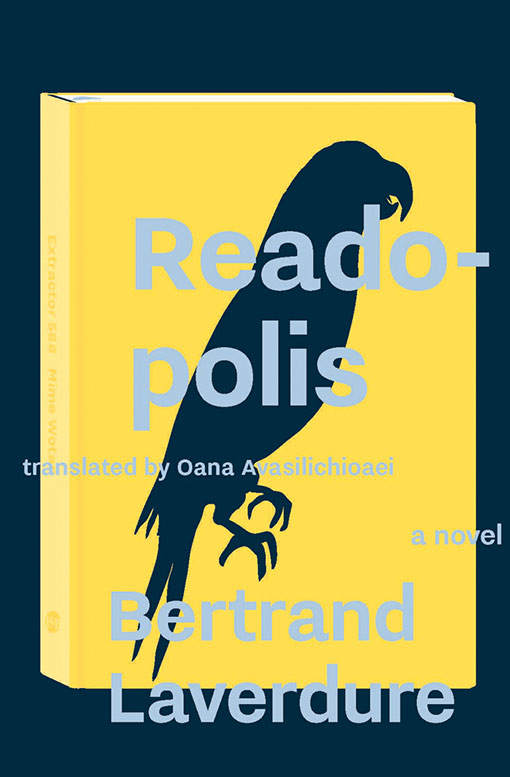

Feature Friday: Readopolis by Bertrand Laverdure, Translated by Oana Avasilichioaei

For this edition of Feature Friday, we’re pleased to bring you an excerpt from the novel Readopolis by award-winning author Bertrand Laverdure, translated by Oana Avasilichioaei. BookThug is pleased to be Bertrand’s English language publisher. Readopolis (Lectodôme in the original French) is his second novel in translation with BookThug, after 2014’s Universal Bureau of Copyrights, which was also translated by Avasilichichioaei. We’re also excited to announce that we’ll be publishing the English language translation of his latest novel, La chambre Neptune, in 2020.

In the pages of Readopolis, we meet down-and-out protagonist Ghislain, who works as a reader for a publishing house in Montreal. It is 2006, and Ghislain is bored with all the wannabe writers who are determined to leave a trace of their passage on earth with their feeble attempts at literary arts. Obsessed by literature and its future (or lack thereof), he reads everything he can in order to translate reality into the literary delirium that is Readopolis—a world imagined out of Chicago and Montreal, with few inhabitants, a convenience store, a parrot, and all kinds of dialogues running amok: cinematic, epistolary, theatrical, and Socratic. In Readopolis, Laverdure playfully examines the idea that human beings are more connected by their reading abilities than by anything else.

From Readopolis

Chapter 1

I’m resting.

Dozing off. Doing nothing, just resting.

All I want is to lie in bed, arms out like a cross, left cheek on the pillow, legs and chest flat on the mattress. I haven’t read anything today and won’t read anything before one in the afternoon. I am a reader—what publishing houses call “a member of the editorial board.”

Yet there is no editorial board, no summit meeting, no secret gathering to formulate impartial, obvious decisions, ones that are democratic and positive. I am a reader because I have my own view of literature: what it should be; what buttons to sew on a novel’s sleeves; what zippers to place throughout a narrative; the ideal length of writers’ detestable pipe dreams.

My plight is to rule over the ghosts haunting the world of letters. Deep down, I will always be Hercules standing before the Augean Stables. I devote myself to a soldier’s anonymous life. I am sent to the front of others’ words, the unbearable, lachrymose bundles of Monsieur Patenaude and Madame Lefebre, Monsieur Hogarteen and Madame Willoska. The unbelievable heap of manuscripts pollutes my consciousness.

Who wouldn’t slam into the first wall they see, having realized the sheer madness of human beings, their disrespectful desire to impose all their misfortunes and opinions on us? If it were up to me, I would decree a law against abominable books.

In fact, I abhor all these smooth talkers, these idolaters of the freedom of expression. Okay fine, I get it, people need to express themselves, rejoice, appease their egos, pour out their bitterness, recount their troubles, but then they get it into their heads to publish this Mother of Vinegar, this thick syrup—no, I say! Asinine nonsense. Kill off the whole lot of blowhards, wipe these battalions of human expression off the face of the earth.

I’m resting.

I won’t say that I recant, lose my head, sometimes have regrets. But I’m weary, I feel my calm slipping away.

I read because others’ torments are part of my labour. I read because the harshest truths and the most ordinary dramas—not to mention extravagant desires—emerge between the clumsy lines of the worst fictions.

Authenticity rests in the clumsiness of writers.

I move only because the earth is round. I lose my temper only because talent is everywhere; it is spherical, omnipotent, unstoppable, flimsy, murky.

What do we learn from reading a good book, a book that affects and moves us?

What do we learn, exactly? How does this experience enrich us, help us transcend our daily worries?

❧

Order your copy of Readopolis here.

Credit: Pascal Lysaught

Bertrand Laverdure is a poet, novelist, and the current Poet Laureate for Montreal (2015–17). A prolific writer, Laverdure is the author of three books of poetry and four novels, including Lectodôme (2008), Bureau universel des copyrights (2011; published in English by BookThug as Universal Bureau of Copyrights in 2014), and La chambre Neptune (2016). He has won many awards for his work, including the 2003 Grand Prix du Festival International de Poésie de Trois-Rivières, and the 2009 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for Lectodôme.

Credit: Pam Dick

Montreal-based writer, translator, and editor Oana Avasilichioaei has published five poetry collections, includingExpeditions of a Chimæra (with Erín Moure; 2009), We, Beasts (2012; winner of the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry from the Quebec Writers’ Federation) and Limbinal (2015). Previous translations include Bertrand Laverdure’s Universal Bureau of Copyrights (2014; shortlisted for the 2015 ReLit Awards), Suzanne Leblanc’s The Thought House of Philippa (co-translated with Ingrid Pam Dick; 2015), and Daniel Canty’s Wigrum (2013).