The Art of Poetry Roundtable, Part One

Poetry, like any art form, is a practice. To be a poet means mastering a certain discipline, finding one’s vocation and siphoning inspiration into form.

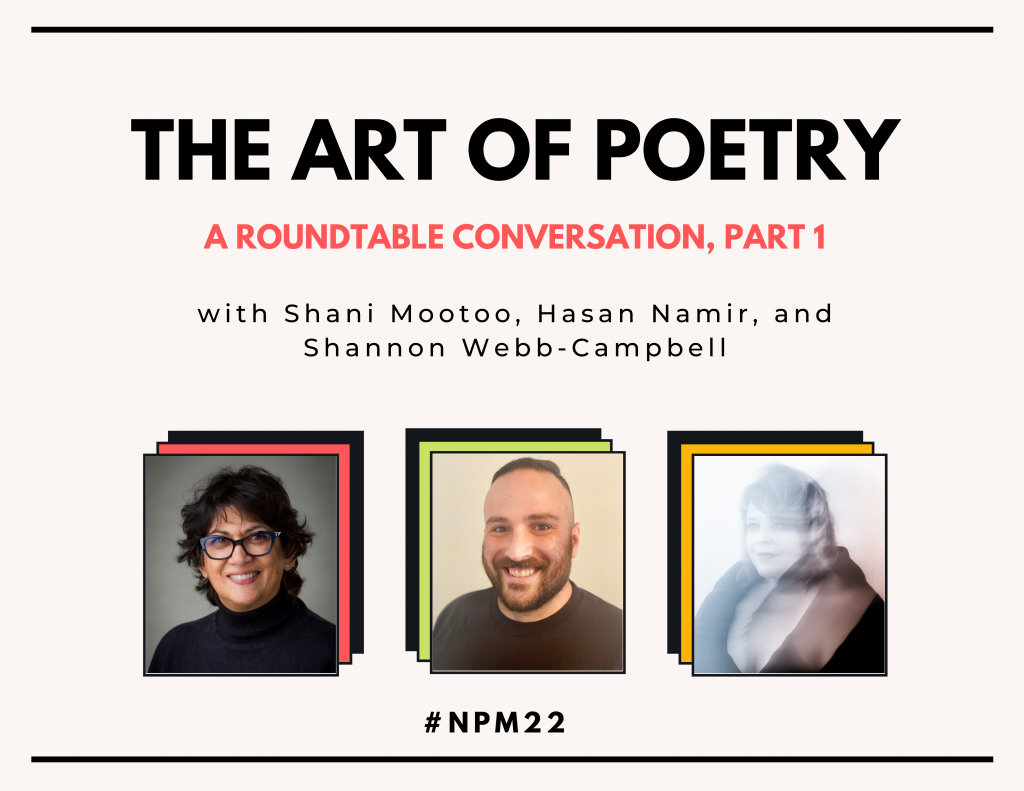

This National Poetry Month we are inviting Book*hug poets to the blog to discuss their creative practice and some of the beliefs and influences that animate their final works. Read on for Part One of a two part roundtable interview series on the Art of Poetry, featuring three acclaimed poets whose recent books all draw on aspects of memoir and find rhythms in personal feeling: Shani Mootoo (author of Cane | Fire), Hasan Namir (author of Umbilical Cord), and Shannon Webb-Campbell (author of Lunar Tides).

B*H: How did you find your way to poetry?

Shani Mootoo: In my youth I wrote with some consistency what I called poetry. The idea of novel writing came decades later and is what was first published. Writing, in my early days, what looked like poetry began as a form of writing that allowed me to explore and excavate the chaos and confusions of growing up while necessarily obfuscating meaning. At the time, poetry was a kind of veil; I said, and at the same time, did not say, all the while writing my complicated self into existence. In time, I grew bolder and didn’t want to hide, but wanted to speak and be seen and heard.

Hasan Namir: I started writing poetry at a very young age, when I was around 13 or 14. I was always drawn to poetry when I was feeling sad, low, and I wanted an outlet for my emotions. Poetry helped me heal my wounds and it gave me a sense of fulfillment. It was very therapeutic. Poetry gave me the freedom to write without barriers and restrictions.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: I blame Susan Musgrave. I took a poetry course with her during my MFA at UBC, and came out of it a poet. Susan made poetry seem artfully seductive, clever, clarifying and just the right amount of danger.

B*H: Desk, café, library, or outdoors?

Shani Mootoo: Armchair, desk, airplane, café, patio, rock (a big one), beach, lap, veranda, hammock, dining table. But not library—too intimidating, too much pressure.

Hasan Namir: I have a full-time job and what I do is I bring my laptop with me and I write on my breaks in my office. Sometimes in the evenings and on weekends, I write in the living room or on my bed.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: I write a lot on my phone while I am walking. I also love sitting in a café with a cappuccino or cortado and a notebook. I used to write a lot on planes and trains as my life was rather transitory, but these days I am content to write at a desk, or comfy chair. Anywhere with some fresh flowers.

B*H: Pen, pencil, or word processor?

Shani Mootoo: All.

Hasan Namir: I use my laptop for all my writing.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: Pen, pencil, and word processor.

B*H: Do you start with a single poem, or an idea for a book?

Shani Mootoo: An image, a phrase, a line. And that might be it. It is difficult to imagine a book when you have a stack of poems that all seem fine, but each one very different from the next. Then there’s the happy occasion when the train of thought that went into a single poem provokes another on the same ‘topic’, in the same vein. Then another. Suddenly there is a handful and one has the insatiable urge to push along those lines.

Hasan Namir: I always start with an idea for a book. I always come up with an outline and themes for my book before I start writing the poems.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: A single poem.

B*H: What do you do if you hit a wall or feel discouraged during the writing process?

Shani Mootoo: Cook an elaborate meal that requires lots of juggling and all my inventiveness and attention. Go on a photography binge. Immerse myself in learning new ideas or a skill. Shower. Showers are great for unintentional brainstorming.

Hasan Namir: I take a break from writing. Sometimes a week or two. Then I revisit what I have written already and go from there. Sometimes, I find music helps me and sets the emotions for me. I would feel calm and then I would write.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: I try and give myself some time and space to explore. I stop hitting the wall and get outdoors. I breathe deeply into my body. Sometimes it can be as simple as walking around the block, or sitting in a new space (a café, or hotel lobby), and when I really need to get myself out of a funk, and I can, I get on an airplane and see life from a bird’s eye view.

B*H: How do you land on a title for a poem? Is this act of naming important to you?

Shani Mootoo: Yes, the act of naming is important. The poem’s name always seems to be hidden in the poem—maybe even the words of the title themselves.

Hasan Namir: The title will come after I finish writing the poem. I re-read the poem and then I come up with a word, a phrase that sums it up. To be honest, titles aren’t so important to me. But I recognize the importance of having titles, along with some sort of structure for my poetry books. Since publishing, I’ve always been giving my poems titles, to give them an identity.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: The act of naming is important to me. The title is the opening line of the poem, so it’s just as important as the poem itself. The title I start the poem with is rarely the title I end with. Sometimes titles come long after the poem, or they are nestled within the poems themselves.

B*H: What’s the last book of poetry you read that moved you?

Shani Mootoo: I can look at and read, again and again, Morning, Paramin, a collaboration between Scottish Trinidadian visual artist Peter Doig and St. Lucian Trinidadian poet Derek Walcott, two masters of their arts. Walcott responds in poems to Doig’s paintings of scenes of Trinidad landscape and life.

Hasan Namir: Why I Was Late by Charlie Petch. Such a powerful and moving collection of poetry that I read twice. I highly recommend it.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: I’ve been a longtime fan of eco-poet Sue Sinclair, and her most recent and collected works Almost Beauty published by Goose Lane, was like wandering with an old friend through the woods and discovering new mushrooms growing along the earth’s bed together. Her philosophical writing is like mossy light, all lichen and love.

B*H: What can poetry do that fiction and nonfiction cannot?

Shani Mootoo: From the p.o.v. of writer and reader, it can reduce noise, illuminate meaning succinctly, in a pithy, unique way. Most poetry seems to me to be a form of non-fiction. Poems can be more dreamlike than fiction and long prose nonfiction, and its appreciation borrows from the tradition of dream analysis and the acceptance of and delight in, segues and non sequiturs. From the p.o.v. of writing it, there is also pleasure akin to that of figuring out a puzzle on numerous levels.

Hasan Namir: Poetry gives the writer the ability to experiment with form and words. Poetry doesn’t have to follow a linear time-line. With poetry, as a writer, I can make my own rules, share what I feel comfortable sharing, and I can be subtle about certain topics and themes. Poetry doesn’t always have to make sense…sometimes; it’s not as accessible but that’s because poetry can embody the author and it’s such a fascinating form of art.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: Poetry can change us in an instant. Poetry is visceral. A single poem can contain what an entire novel and work of non-fiction attempts to convey in hundreds of pages.

B*H: Is there a poem you have written that has remained particularly meaningful to you/close to your heart?

Shani Mootoo: I wrote “Ancestry” decades ago. My mother is not an Anglican, and my father is not a priest, but I wanted to capture the odd bits of phrases and imagery that popped into my mind unsolicited, and to let rule what I came to trust as an all-knowing subconscious. It was a highly instructive practice I used at the time for writing and artmaking. The poem had remained untitled and unpublished until now because I hadn’t before found an appropriate venue for it. To my delight, my new poetry book Cane | Fire provided the perfect venue for presenting it, and the through-line of the book helped with giving the poem a title. And so “Ancestry” is now, finally, published:

My mother was an Anglican

My father was a priest

Together they prayed real hard

When spring came (and the Pitch Lake overflowed)

They reaped the smoothest stones you’ve ever seen

Hasan Namir: “I Am A Father” and “Umbilical Cord” from my latest poetry book Umbilical Cord always bring out emotions when I read them. These poems bring back many memories. I try really hard to fight the tears when I read them at book events and festivals.

B*H: What advice would you give to your younger self, or yourself as a poet just starting out?

Shani Mootoo: Read tonnes of poetry, read with your eyes, little Shani, and with your heart. Read as if you yourself wrote the poems of the masters, and delight in the choices you made. See what you/I might have said instead, but then delight in those final choices. And even if it is only a line, jot one down every day. That one will likely nag you/me, and might just evolve into something worthwhile.

Shannon Webb-Campbell: Be gentle with yourself. Like everything, poetry is a process. You’ll grow better with time, age and multiple revisions. Don’t be so afraid to share your work with others.

Shani Mootoo was born in Ireland, grew up in Trinidad, and lives in Canada. She holds an MA in English from the University of Guelph, writes fiction and poetry, and is a visual artist whose work has been exhibited locally and internationally. Mootoo’s critically acclaimed novels include Polar Vortex, Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab, Valmiki’s Daughter, He Drown She in the Sea, and Cereus Blooms at Night. She is a recipient of the K.M. Hunter Arts Award, a Chalmers Fellowship Award, and the James Duggins Outstanding Midcareer Novelist Award. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, and includes the collection, The Predicament of Or. In 2021 Mootoo was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Letters from Western University. Her work has been long- and shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Dublin IMPAC Award, and the Booker Prize. She lives in Prince Edward County, Ontario.

Hasan Namir is an Iraqi-Canadian author. He graduated from Simon Fraser University with a BA in English and received the Ying Chen Creative Writing Student Award. He is the author of God in Pink (2015), which won the Lambda Literary Award for Best Gay Fiction and was chosen as one of the Top 100 Books of 2015 by The Globe and Mail. His work has also been in media across Canada. He is also the author of the poetry book War/Torn (2019, Book*hug Press) which received the 2020 Barbara Gittings Honor Book Award from the Stonewall Book Awards, and children’s book The Name I Call Myself (2020). Hasan lives in Vancouver with his husband and child.