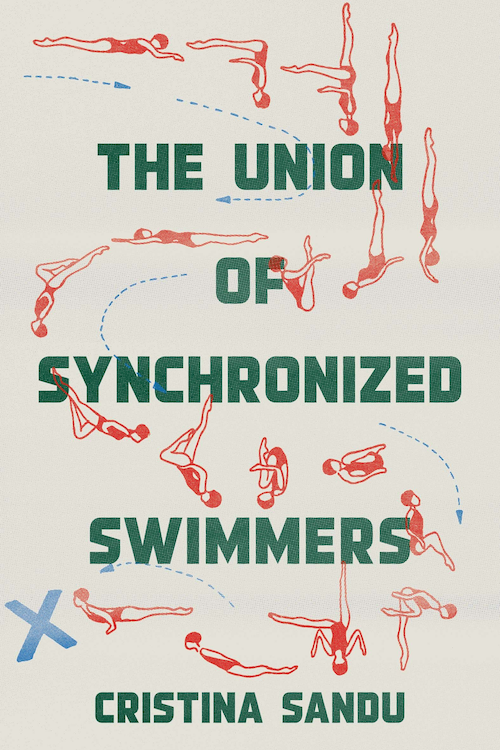

Spring Fiction Preview: The Union of Synchronized Swimmers by Cristina Sandu, Translated by Cristina Sandu

Friends of Book*hug, meet Spring 2021. Earlier this year, we unveiled the forthcoming titles in our Spring 2021 season, but now it’s time to get to know the authors and their books a bit better. For the next couple of months, we’ll be highlighting individual spring titles, and sharing some thoughts from the authors and some exclusive excerpts on the blog.

Today, we’re excited to preview The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, written and translated from the Finnish by award-winning author Cristina Sandu. In Sandu’s English debut, six girls begin a journey to the Olympics. In a stateless place, on the wrong side of a river separating East from West, the girls meet each day to swim. At first, they play, splashing each other and floating languidly on the water’s surface. But as summer draws to an end, the game becomes something more.

They hone their bodies relentlessly. Their skin shades into bruises. They barter cigarettes stolen from the factory where they work for swimsuits to stretch over their sunburnt skin. They tear their legs into splits, flick them back and forth, like herons. They force themselves to stop breathing.

Then, one day, it finally happens: their visas arrive.

Sandu is one of Finland’s most exciting contemporary writers. Her debut novel, The Whale Called Goliath (2017), was nominated for the prestigious Finlandia Prize, and The Union of Synchronized Swimmers was awarded the Toisinkoinen Literary Prize in 2020. We look forward to sharing Sandu’s English-language debut—which author Lindsay Zier-Vogel calls “exquisite and powerful”—with Book*hug readers.

As promised, we’ve selected an excerpt from The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, which you can read and enjoy below. The book is forthcoming from Book*hug Press on June 22nd, 2021, and is available now for pre-order, either in our online shop or from your local independent bookstore. Be sure to stay tuned for more exclusive, never-before-seen sneak peeks of our Spring 2021 season, and follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

When spring came, the girls were the first at the river. They left their clothes in bundles on the bank, stretched their bodies in the sand, and ran into the water. The cold was sharp. They smoked with just their heads above the surface, blew smoke into the sky, and laughed with their necks tilted back. Ashes scattered on the water, which held their white breasts like doves.

Empty soda bottles, eggshells, chicken bones gnawed bare, bread crusts, and cheese that had melted, cooled, and then congealed were all scattered across the picnic blanket. A yellow tractor stood in the mud close to the bank. A hen was laying eggs behind on of its wheels. A pig was bathing in the river. Farther out were six other swimmers.

The girls started to play, though they were too old; their movements were aimless at first, like they could ’ve been doing anything else. They plunged into the water and sprang up, parting the surface with their hands. They crept among the reeds and made birds scatter from their nests. They tore flowers growing by the river and drew shapes in the air.

They pushed each other’s heads under the surface and held them there, as if performing a baptism. They stood on their hands in the water, their feet swinging madly against the branches of the trees.

Now, there are places that are on the wrong side of the river and places that are on the right side. When the girls sat on the shore, they looked from the wrong side across to the right side, on the bank of which a wharf extended.

The land where the girls lived didn’t belong to any country. Its name meant the Near Side of the River. Its beauty was the only kind they knew. The cement buildings of the city, the blue-roofed monastery at the top of the only hill, the war memorials and the stony Lenins that had escaped demolition after the fall of the Republic. The profiles of the metal and cigarette factories, which grew huge at night and loomed over the houses. The pigeons and dogs that ambled through the streets. The town belonged to them, too. It was surrounded by forests, meadows, green and yellow fields, the river, and other towns with little cottages.

But a silence pervaded the land: for most of the year, the men were gone. They grabbed any kind of work they managed to get in a neighbouring country. They sent letters and packages home, and came to visit when they had enough money or their homesickness had become too great.

Only the women stayed. They kept life going. They worked the land, fed and slaughtered the animals, raised the children. They ensured that the metal factory filled the sky with red smoke. They prepared the cigarettes, cramming them neatly into elegant white packs, which then went on to fill glistening cartons to be shipped far away, by land and by sea.

Cristina Sandu was born in 1989 in Helsinki to a Finnish-Romanian family who loved books. She studied literature at the University of Helsinki and the University of Edinburgh, and speaks six languages. She currently lives in the UK and works as a full-time writer. Her debut novel, The Whale Called Goliath (2017), was nominated for the Finlandia Prize, the most prestigious literary prize in Finland. The Union of Synchronized Swimmers, which won the 2020 Toisinkoinen Literary Prize, is her first book to be published in English.