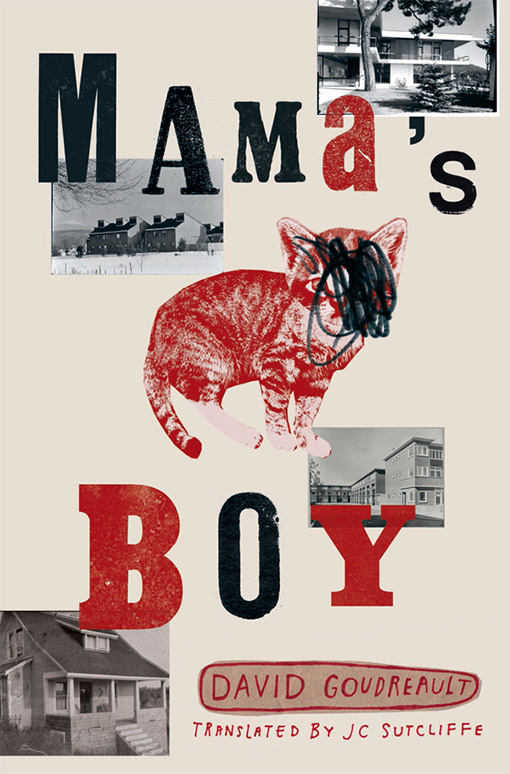

Feature Friday: Mama’s Boy by David Goudreault, Translated by JC Sutcliffe

In this week’s edition of Feature Friday, we are very excited to bring you an excerpt from David Goudreault’s Mama’s Boy, translated JC Sutcliffe. Written with gritty humour in the form of a confession, Mama’s Boy recounts the family drama of a young man who sets out in search of his mother after a childhood spent shuffling from one foster home to another. Featuring a bizarre character with a skewed view of the world, he leads the reader on a quest that is both tender and violent.

The Huffington Post calls Mama’s Boy “a tour de force first novel: percussive, with vivid imagery, chiselled and rhythmic, a novel one will not easily forget.” Kim Thuy, author of Vi and Ru, writes, “David Goudreault will captivate you from the first line!”

A runaway bestseller among French readers, Book*hug is excited to be David’s English language publisher for the first book in a trilogy that took Quebec by storm, winning the 2016 Grand Prix littéraire Archambault, and selling more than twenty thousand copies. Mama’s Boy Behind Bars is the second book in David Goudreault’s wildly successful and darkly funny trilogy, and is set to be released in June of next year.

We hope you enjoy this excerpt from Mama’s Boy. Happy reading!

From Mama’s Boy:

The first time I killed a cat, I was as surprised as he was. In fact, as surprised as she was, since it was a little molly cat called Mimine. Mimine was a pretty product of back-alley mating, her bastard coat cleverly mixing brown, black, and ginger. She was a full-fledged member of my foster family at the time, the Doucets. I would have been fifteen then; Mimine was three.

For several months, I’d been in the habit of torturing animals whenever I was frustrated. I must have been very frustrated on that particular day. The animal didn’t survive the combination of centrifugal force and my bedroom door frame. It made an odd noise, soft and dry at the same time. I was sitting on the bed, still holding Mimine by the tail, when there was a creak on the stairs.

Robert was coming down. I panicked. I slid the cat under the duvet and stretched out on top of it. What noise? No, it wasn’t me that had made that noise. No, I hadn’t nailed anything to the wall. Yes, I was coming up for dinner. Robert, the debonair patriarch of this reasonably functional family, had his eye on me, the eye of the tiger. He couldn’t manage without the cash that social services gave him for looking after me, but never stopped telling me he’d had it up to here with my crap and I was this close to being shown the door. I didn’t particularly like his dump of a house, or the people who lived in it, but I was fed up with moving. I liked having my own room in the basement, away from everyone else. And above all, this was the first foster home that had the Super Écran channel. After midnight on Fridays, Super Écran was fantastic.

I had to get rid of the body.

As per usual at this house, I wasn’t allowed to go out that Sunday. I rolled the corpse up in a towel and stashed it between the mattress and the box spring for the day, waiting for Monday morning. Part of the evening was taken up with searching for the missing cat. I was particularly energetic in my efforts. The family lingered in my room but without any luck.

Fortunately for me, I was already seriously into hip hop, and wore it proudly. My oversized pants meant I could attach Mimine, with the help of some duct tape, to my inner left thigh as I was leaving the house. The corpse’s stiffness restricted my movement a fair bit, but I managed to walk more or less normally. Enough to eat, then leave the house, without being noticed. With my schoolbooks under my arm, I went down the street, cursing myself for having traded my backpack for a tab of LSD. My thigh had started itching and was getting worse by the minute. I’d pulled the tape too tight. My leg was completely numb. Although maybe it was better that way, since the fur tickled less. The bus ride went on forever, there were three of us in one seat and I couldn’t discreetly scratch my crotch.

Once I’d made my careful way to school, I smoked my morning cigarette and then headed for the toilets. Sitting on the throne, Mimine’s body across my knees, I waited for the bell to ring and the washrooms to empty out, then I concealed the proof of my crime in the garbage under a pile of dirty paper towels. I had to run to class. I needn’t have bothered—the teacher was already writing me a detention slip.

It was an ordinary school day. Brainwashing, surging hormones, and putting up with a bit of intimidation that was immediately passed on to anyone smaller. I liked the bustling atmosphere, and I really liked the girls. In return, they didn’t particularly like me. I had a bad reputation and was too mature for my age. I never managed to screw any of them. My sole forays into teenage sex took place hidden behind a rusty merrygo-round at the fair. The girl was slightly retarded and ugly, so it doesn’t really count. Sometimes I regret that I didn’t know how to meet those nymphettes’ expectations back then. I caught up later.

Although Operation Camouflage was successful, Mimine’s disappearance was still blamed on me. They argued that the cat had never run away before, that Robert had heard a door slamming the previous day, that I smoked in secret, and that I must have let her out when I came through the garage. They were accusing me without proof. This felt like a grave injustice. I kicked a hole in the wall to show my indignation. I was quickly moved to another foster family. This one had a dog.

❧

Order your copy of Mama’s Boy here.

David Goudreault is a novelist, poet and songwriter. He was the first Quebecer to win the World Cup of Slam Poetry in Paris, France. David leads creative workshops in schools and detention centres across Quebec—including the northern communities of Nunavik—and in France. He has received a number of prizes, including Quebec’s Medal of the National Assembly for his artistic achievements and social involvement and the Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for his first novel, La Bête à sa mère (Mama’s Boy). He is also the author of Le bête a sa cage and Abattre la bête, both of which will appear in English translation from Book*hug. He lives in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

David Goudreault is a novelist, poet and songwriter. He was the first Quebecer to win the World Cup of Slam Poetry in Paris, France. David leads creative workshops in schools and detention centres across Quebec—including the northern communities of Nunavik—and in France. He has received a number of prizes, including Quebec’s Medal of the National Assembly for his artistic achievements and social involvement and the Grand Prix littéraire Archambault for his first novel, La Bête à sa mère (Mama’s Boy). He is also the author of Le bête a sa cage and Abattre la bête, both of which will appear in English translation from Book*hug. He lives in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

JC Sutcliffe is a writer, translator, book reviewer, and editor who has lived in England, France, and Canada. She has reviewed for the Times Literary Supplement, The Globe and Mail and the National Post, among others.